You’d be forgiven for any skepticism about the Donmar Warehouse production of Blindness, a new audio installation-cum-stageplay on now at the Princess of Wales Theatre. An adaptation of José Saramago’s celebrated novel Blindness (“Ensaio sobre a cegueira“), this first major production of the Toronto theatre season sits fifty socially distanced audience members at a time, each sporting headphones tuned into the same 75-minute pre-recorded drama.

Is it a glorified radioplay? Kinda. Does it come at a time where the idea of sitting in a darkened space, surrounded by strangers, is unusually unnerving? Absolutely. But Blindness also offers something special, something that can’t be captured alone, at home, not even with the best headphones: it reminds us of why we love theatre.

DARK TIDINGS

Blindness arrives in Toronto following a sell-out run in London, where a team of very wise artists at the Donmar, faced with the challenge of welcoming back uneasy theatregoers, landed on an idea for a show requiring no actors, a reduced audience, and the ability to mount multiple performances per day. The drama’s sole narrator, Juliet Stevenson (Truly, Madly, Deeply), recorded all her lines in studio, while a skeleton crew is on-site for each performance to oversee its wonderfully designed sound and visual effects.

Blindness is set in an unnamed city plagued by an epidemic of blindness. From one day to the next, people begin losing their sight, and soon enough a panicked government is rounding up those afflicted and placing them in hospital/detention, from which point things deteriorate rapidly. Although it’s implied the epidemic is of at least national scale, the vast majority of the story is told from a much narrower perspective, that of the small band of individuals first stricken with blindness. This particular production focuses on one person among them, an ophthalmologist’s wife, who for unexplained reasons is the only one to retain her sight (though she hides this fact from the others). It is through her eyes – or, in this case, her voice, narrated perfectly by Stevenson – that we are confronted with the cascading horrors of the new world in which she finds herself: the too-quick descent into violent tribalism; the repugnant living conditions of a population resigned to its fate; the rampant abuse and exploitation of the weak by those strong or cruel enough to do so.

While Blindness carries added resonance in 2021 (it’s hard not to cringe the first time Stevenson intones the word “quarantine”), Saramago himself described his novel as an allegory for the “blindness of rationality“, the rapid decline of his blind society acting as a mirror for our own inability to help our fellow humans. (In eerily prescient words, Saramago’s 1998 Nobel acceptance speech lamented how the “same schizophrenic humanity that has the capacity to send instruments to a planet to study the composition of its rocks can with indifference note the deaths of millions of people.”) But even if you were unfamiliar with this background, Blindness works well enough as a study in what happens to an unprepared society when things go terribly, terribly wrong.

BRIGHTEST DAY

Blindness, the novel, is not an obvious fit for adaptation. Its prose is dense, difficult to follow, and devoid of most standard punctuation, while its violent, despairing content hardly seems audience-friendly. And yet, since its 1995 publication, Blindness has been adapted into everything from a fringe production to opera, not to mention a 2008 film adaptation scripted by none other than Toronto’s own Don McKellar. (McKellar and director Fernando Mereilles somewhat famously travelled to Saramago’s home in the Canary Islands, spending two days convincing the reluctant author to sell them the film rights.)

As an audio installation, Blindness makes perfect sense. Much of the production takes place in darkness, the headphones’ impressively crisp 3D audio mimicking the sensation of sharing a space with Juliet Stevenson. Until you’ve actually heard Stevenson “traverse” the room – starting over there, circling behind you, walking off some distance, then sneaking up and whispering in your ear – it’s hard to explain just how immersive it really is. I know I’m not the only audience member who tucked in their feet for fear of tripping Ms. Stevenson as she “passed by.” This is surround sound unlike anything you’ve heard before.

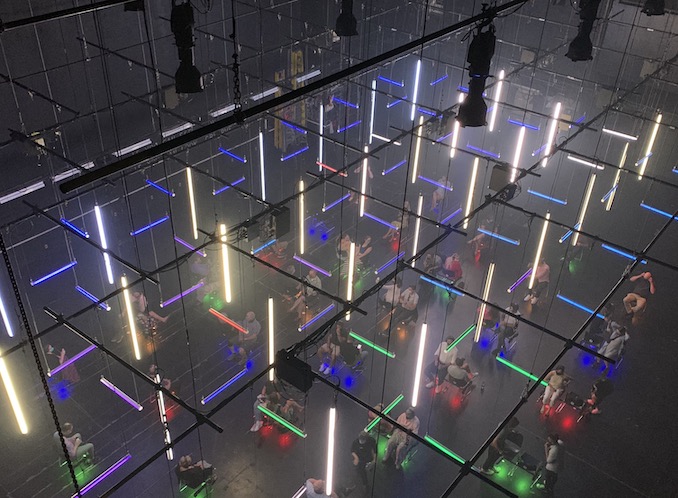

Ironically for a drama on this particular theme, the set design is also a major draw. The set is sparse – an all-black room, mostly (though, annoyingly, not entirely) light-proofed, decorated only by a sea of hanging lights, which shift colour, intensity, and position over the course of the show. A gunshot, for example, might be accompanied by the flash of a single bulb, while a stunning blaze of bright orange light might signal the dawning of a new day. And though, as mentioned, it mostly takes place in darkness, the judiciously-lit set does have a couple surprises in store, including one very entertaining visual joke for those paying attention.

LIGHTNESS OF BEING

As we take our first halting steps into the almost-post- but not-quite-post-pandemic world, there’s solace to be found in the familiar sights and sounds. Friends laughing at restaurants; spilled coke and popcorn at a cinemagoer’s feet; an intimate meal in the darkened corner of a favourite restaurant. Theatre, too, can be a balm, even when what’s on stage (or in our ears) bears an uncomfortable resemblance to our own experience. Though if Blindness was solely a tale of sound and fury, of misery and despair, it would be that much harder to recommend.

But Blindness is more than that. Though many in its fictional environs give in to their baser instincts, there are also those who resist, who refuse to abandon their humanity. And when even they do give in, when they commit terrible acts in the name of survival, or simply of frustration, we are not supposed to condemn them, but rather to feel pity. Saramago, who passed away in 2010, would understand our current moment too well: the haphazard governmental response to a crisis requiring decisive action; the failure of communities to cooperate; the resistance of the ignorant and the easily misled. But Saramago would understand the good parts about it too: the small acts of kindness; the eventual rallying of resources and of communal goodwill to bring this crisis under control; and now the first, faint hope of what lies on the other side. Saramago’s Ensaio sobre a cegueira did not predict 2021, but the Donmar’s Blindness is a perfect response to it.

***

Blindness is on now at the Princess of Wales Theatre until August 29. Tickets are available here.