The 150th anniversary of Confederation, Canada’s sesquicentennial, is a suitable prompt for recommended reading. Rather than simply list the best five Canadian novels – as fine as these are – I elected to seek five novels that are oddly suitable for reading in 2017. Each of these books was chosen for a particular resonance with here and now – with current events, with popular culture, or with Canadian identity. For a reader so inclined, each of these novels can provide a point of reflection on “Canada” as we have, could, or should understand it. So without further ado…

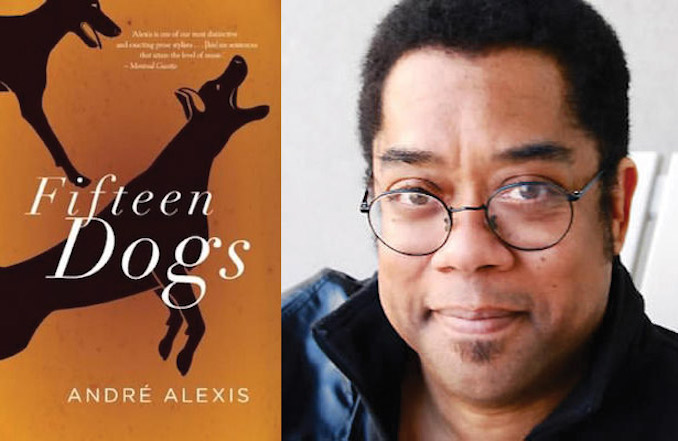

Andre Alexis – Fifteen Dogs (2015). I had the good fortune of hearing Alexis read from this novel when it was a work in progress. The premise immediately engaged me: Apollo and Hermes, out drinking in downtown Toronto, capriciously grant human intelligence to some unsuspecting dogs. The dogs’ various efforts to reconcile their newfound awareness with their older instinctive understanding of the world animates the plot. It’s light and fun, but it’s also heavy in the right places. This novel has found audiences the way it won my attention, taking the Giller Prize and Canada Reads. I want to single out Fifteen Dogs not just as a good book, but as one to read in 2017. Canadian arts and culture continue to bear the weight of a relentlessly grinding international monoculture. Meanwhile our giants and literary heroes are aging and fading away – this past winter, for example, we lost Leonard Cohen. But this novel demonstrates that Canadian identity is neither invested in a small coterie of beloved figures, nor endangered by forces from without. Fifteen Dogs is an opportunity to read a thoughtful and entertaining novel of the here and now. It’s a reminder that great things are happening in Canada.

***

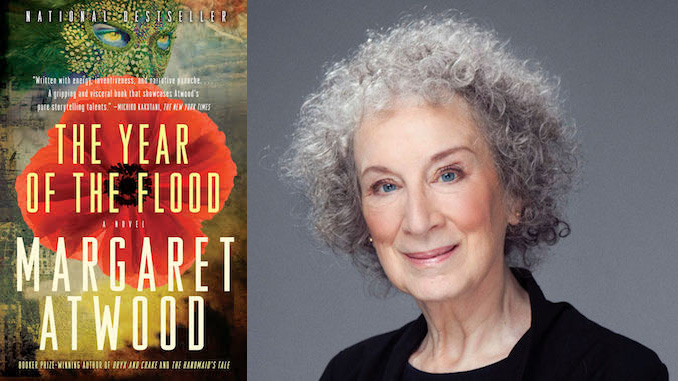

Margaret Atwood – The Year of the Flood (2009). Atwood may be low-hanging fruit on a list like this, but her dystopian masterpiece trilogy earns more than emeritus lip service. The Year of the Flood flings a remorseless satirical gaze across the carnivalesque failures of modern industrial capitalism. Her near-future setting calculates implications of early twenty-first attitudes towards culture, environment, human rights, and the status of women. Many of these indictments seem even more apt in 2017. The sci-fi world building is less detailed than Oryx and Crake’s genetic engineering and cloak-and-dagger plots, but The Year of the Flood is a more human story. The plot follows two young women’s separate experiences in God’s Gardeners, an apocalyptic environmentalist sect which preaches pacifism, oneness with nature, and survivalist skills, while canonizing such figures as Saint Dian Fossey and Saint Jacques Cousteau, among more familiar objects of worship. Its characters are charming, and much pleasure is to be found in watching them construct a little utopia in a decaying, degenerate world. If you sit down to read it, make sure that a copy of MaddAddam, the final book in the trilogy, isn’t too far out of reach. It also wouldn’t hurt to read Oryx and Crake first, but the plots of the first two books are largely simultaneous.

***

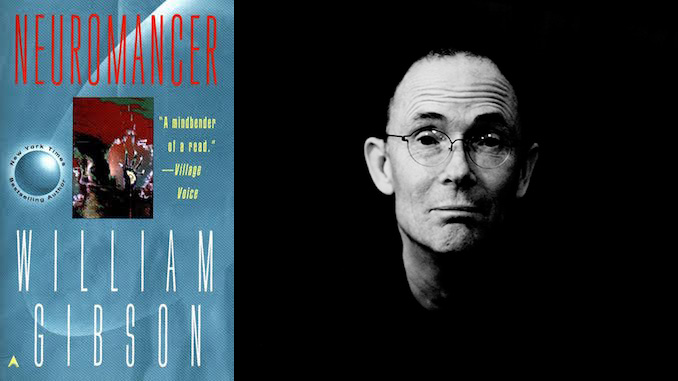

William Gibson – Neuromancer (1984). Vancouver’s Gibson’s globetrotting cyberpunk classic is always a good choice, especially for the first-time reader. Hackers, gangs, and “street samurai” struggle for survival in overcrowded, over-developed, and criminalized cities. Amid it all, Case and Molly are hired into a mysterious mercenary scheme which leads them through the holdings of governments, futuristic super-corporations, space Rastafarians, and a caste of semi-immortal super wealthy. The plot turns on an arsenal of sci-fi tech, including cybernetics, neural implants, bioengineering, virtual realities, and artificial intelligence. If gritty adventure isn’t quite your speed, Gibson’s later tech thrillers are also worth a look. His work becomes decreasingly futuristic as “near-future” becomes less distant, even if the super-corps and their inscrutable motives still reign. Idoru, for example, offers a pop-culture driven future of megastars, human-scale AIs, and hidden online societies. Pattern Recognition and Spook Country seem almost contemporary, instead electing to explore the reality-destabilizing implications of what we have rather than what could be.

***

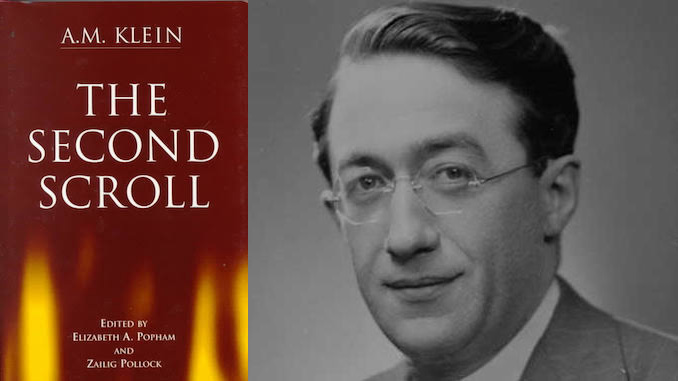

A. M. Klein – The Second Scroll (1951). Klein is best known as a poet, and The Second Scroll is his only novel, though it has long maintained its place in the venerable New Canadian Library series. The Second Scroll follows a Jewish-Canadian man from Montreal in his effort to locate his quasi-heroic uncle in the wake of the Holocaust. The settings of this quest will be familiar to any reader who follows the regular news cycles: the narrator seeks his uncle in the throngs of displaced Jewish refugees in Italy, Morocco, and Israel. The journey becomes something of a pilgrimage. Klein’s strong modernist prose – the prose of a poet – gives immediacy to the entire experience as the narrator encounters xenophobia, anti-Semitism, poverty, and the immediate aftermath of the Nakba. That the novel’s five chapters map onto the books of the Torah adds an air of biblical significance to these events, even if that particular significance remains hidden in conflicted sympathies and greater mysteries. An added treat is that the novel contains its own “glosses” – an experimental endnote device which Klein used to add further colour to his book. The first of these, “Gloss Aleph,” also titled “Autobiographical,” is a first-rate imagist poem about Jewish Montreal.

***

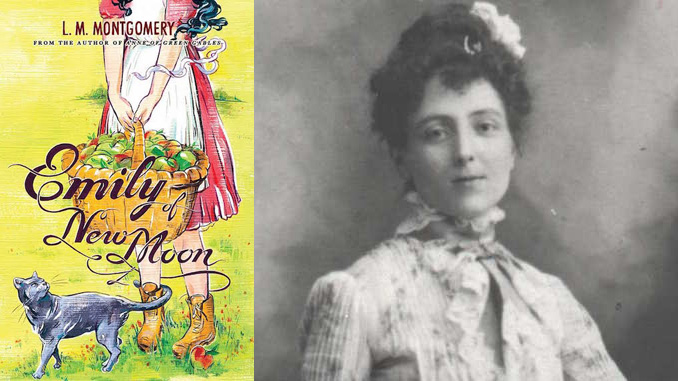

Lucy Maud Montgomery – Emily of New Moon (1923). Alexis, Atwood, and Gibson may challenge the caricature of Canada as a simple, orderly, and polite place, but the nation’s 150th birthday compels us to explore those older caricatures while we challenge them. Appropriately, this summer CBC is launching its new Anne of Green Gables adaptation. An inevitability, and perhaps the public broadcaster’s solemn duty, as the Anne Shirley stories are the bedrock of that quintessential Canadiana. Somewhat less known is Montgomery’s later orphan series, also set in rural Prince Edward Island. Emily of New Moon has more cynicism for rural Canada. Emily shares Anne’s precocity, charm, and intelligence, but unlike the bright pastoral of Green Gables, in New Moon the paint peels and a layer of dust seems to settle on long-forgotten heirlooms. Its residents seem to struggle with their world, and at times with history itself – a far cry from the, confident, rugged Anglo-Canadian settler. In its complication of the classic story of rural protestant Canada, Emily of New Moon is perhaps Montgomery’s own reply to that idyllic to which she contributed so much.

***