Back in 2022, when Sight and Sound Magazine’s decennial poll (controversially) voted Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles the greatest film of all time, it inadvertently shone a spotlight on what many consider the greatest year in film ever.

1975’s Jeanne Dielman… was certainly an interesting choice for critics to rally around. Premiering at Cannes in May 1975, the 201-minute(!) Jeanne Dielman… represents a borderline experimental exercise in slow cinema, depicting three uneventful days in the life of a widowed Belgian housewife in painstaking, if not excruciating, detail.

That May ‘75 release date, however, does offer an interesting counterpoint to all the other, rather more famous releases of that year, Jaws – celebrating its fiftieth anniversary this week – among them. And if box office giant Jaws and Jeanne Dielman… represent the polar opposites of the medium, then 1975’s other releases represent the fascinating spectrum which runs between.

Here, then, are our picks for the best films of 1975 – the year that invented the blockbuster, that solidified Steven Spielberg as the great Hollywood filmmaker, and, in our humble opinion, the best year in cinematic history. (Spoilers: Jeanne Dielman… did not make our cut.)

Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon is a propulsive, nerve-rattling thriller about a bank heist gone spectacularly awry, would-be thieves Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino) and Sal Naturile (John Cazale) turned unexpected hostage takers on a long, hazy Manhattan day. Based on a real incident, its socially conscious themes – including an unusually progressive “twist” – elevate this beyond the trappings of the crime genre it’s nominally working in. With the shadow of the then-recent Attica Prison Riots hanging over it, this raw slice of 1970s New York life is probably the greatest work of the New American Cinema outside The Godfather (1972, also, perhaps not coincidentally, starring Pacino and Cazale).

Steven Spielberg had two features to his name before Jaws, but nothing in Sugarland Express or Duel (well, maybe the evil truck in Duel) could have prepared audiences for the aquatic thrill ride that is Jaws. Enough ink – much of it my own – has been spilt over Jaws, so we’ll just add this bit of trivia: in this two hour movie, the shark only has about four total minutes of screen time in all its teeth-gnashing glory. The rest of the time? Glimpses, shark’s-eye-view shots, and a whole lot of implied carnage just below the water line.

Has there ever been a director with a more consistent and yet wildly varied output than Peter Weir, whose Picnic at Hanging Rock many consider the best Australian film ever made? Weir, who would go on to direct (deep breath) The Last Wave (1977), Gallipoli (1981), The Year of Living Dangerously (1982), Witness (1985), The Mosquito Coast (1986), Dead Poets Society (1989), Green Card (1990), Fearless (1993), The Truman Show (1998), and Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003), was never better – or weirder – than in this 1975 masterpiece. Adapted from the 1967 Joan Lindsay novel of the same name, Hanging Rock depicts the aftermath of the mysterious disappearance of a teacher and three students from an all-girls school on Valentine’s Day, 1900. Proto-Lynchian, Hanging Rock resists easy interpretation, dragging viewers along the same, inexplicable, slow-motion roller-coaster ride as its characters.

Terry Jones and Terry Gilliam might be the credited co-directors on Monty Python and the Holy Grail, but it’s the whole Monty Python crew – which also included John Cleese, Michael Palin, Graham Chapman, Eric Idle, and Carol Cleveland – which deserves credit for this riotously funny first feature bursting at the seams with absurd, hilarious ideas. For our money the best Python film, its obvious affinity for the genre it lampoons – fun fact, despite that “it’s only a model” joke, they did indeed film at a real medieval castle – makes the whole exercise that much better. You’d be hard-pressed to pick a single funniest moment, though we’re partial to the infamous Black Knight duel (warning: NSFW) and the very first scene, with its cries of “Bring Out Your Dead!”

Your mileage may vary with Nashville, Robert Altman’s rambling satire of the country music scene, but if you can accept its (deliberately) risible soundtrack of fake country and western songs, you’re in for a treat. Depicting several topsy-turvy days in the lead-up to a country-fried political rally on behalf of a demagogic presidential candidate, Nashville remains distressingly relevant today. A perfect ensemble cast, including Karen Black, Jeff Goldblum, Keith Carradine, Geraldine Chaplin, Shelley Duvall, and honourary Canadian Michael Murphy, portrays the motley crew of superstars, wannabes, political operators, and laughably pretentious journalists.

The film that basically defined the cult canon, Jim Sharman’s The Rocky Horror Picture Show is even better than its reputation suggests. Between the fantastic, catchy musical numbers, the hilarious screenplay, and the winning performances of Tim Curry and Susan Sarandon, Rocky Horror is a great film in its own right, and that’s before you consider its decades-spanning influence on film, music, pop culture in general, and queer culture in particular. Playing more or less monthly in Toronto – it’s screened recently at the Paradise, the Revue, the Fox, and Hot Docs – it’s an essential big-screen, communal viewing experience.

Arthur Penn is better known today for Bonnie and Clyde (1967), but his long-overlooked Night Moves might be even better. A darkly comedic neo-noir in the vein of Chinatown or The Long Goodbye, Night Moves stars the late Gene Hackman as a private investigator searching for a missing teenage girl (Melanie Griffith, in her film debut). Hackman, who passed away earlier this year, is in fine form in this journey from L.A. down to the Florida Keys, where he encounters a delightfully seedy gallery of creeps and oddballs, including the girl’s nymphomaniac mother (Janet Ward) and deeply unpleasant stepfather (John Crawford). The unexpected ending is phenomenal.

If anyone could give Peter Weir a run for his money, it’s Stanley Kubrick, whose own unbroken streak of masterpieces – beginning with The Killing (1956) and concluding with Eyes Wide Shut (1999) – sees Barry Lyndon land smack dab in the middle. Not Kubrick’s greatest, but better than most films of its era, this 18th-century comic-drama is beautiful to look at, more than a bit cruel, but very funny in its own perverse way. Ryan O’Neal is perfectly cast as Redmond Barry, the too-beautiful scoundrel who cheats, cons, and kills his way to fortune, all against the most stunning natural backdrop ever lensed (earning cinematographer John Alcott an Oscar which probably should have been shared with Kubrick).

The strange, mildly unseemly documentary Grey Gardens, from legendary directing duo Albert and David Maysles, depicts the trials and tribulations of toxically co-dependent mother-daughter duo Edith Beale, Sr. and Edith Beale, Jr. Though the nominal hook is their indirect Kennedy connection – “Big Edie” was Jackie Kennedy’s aunt – this film works equally well as a study of two formerly wealthy women now reduced to near-squalor by a combination of circumstance and unusual life choices. Controversial even at its release, Grey Gardens is perhaps more important today as a seminal entry in the direct cinema movement, which also includes D. A. Pennebaker’s Dont Look Back (1967) and the Maysles’s own Salesman (1969).

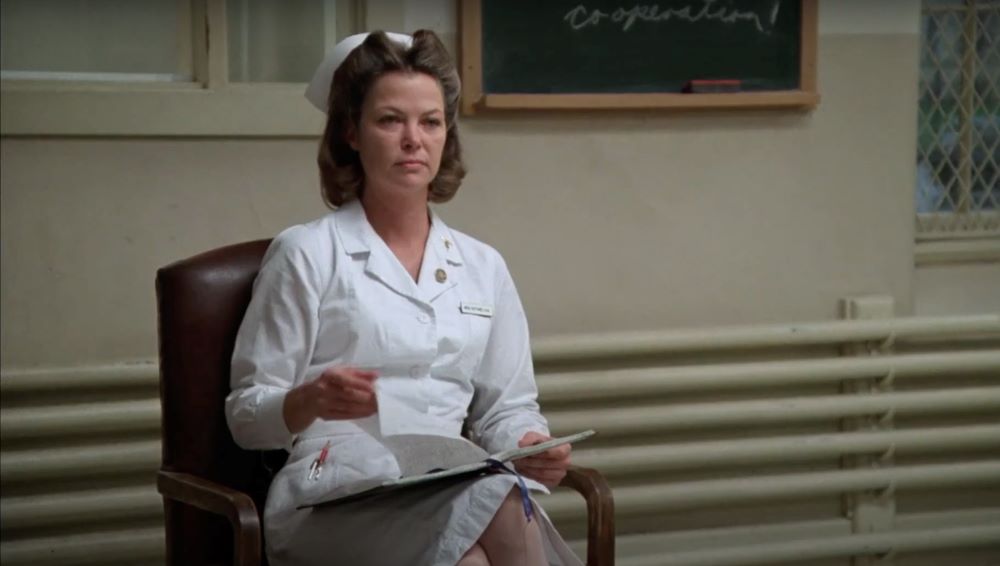

It’s not our favourite Jack Nicholson movie (heck, it may not even be his best performance of 1975, since Antonioni’s The Passenger also came out that year), but there’s no denying the lasting impact of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which effectively set the template for “radical free spirit versus cruel institution” movies. The year’s eventual Best Picture winner, One Flew Over is a searing indictment of the U.S. carceral system, as well as a fine acting showcase for Nicholson, Louise Fletcher as the sadistic (and impeccably named) Nurse Ratched, and a whole host of character actors, including Christopher Lloyd, Danny DeVito, Brad Dourif, Scatman Crothers, and other half-familiar faces. Nicholson and Fletcher both won Oscars for their performances, as did Miloš Forman for directing, and Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman for their screenplay, adapted from the Ken Kesey novel.

Other notable films celebrating their fiftieth anniversaries this year include, in no particular order, The Man Who Would Be King, Love and Death, The Stepford Wives, Shampoo, The Who’s psychedelic rock opera Tommy, delightfully cliché disaster flick The Towering Inferno, Lina Wertmuller’s Swept Away by an Unusual Destiny in the Blue Sea of August (Travolti da un insolito destino nell’azzurro mare d’agosto), Akira Kurosawa’s sole non-Japanese-language film Dersu Uzala (a Soviet co-production), Canada’s own Oscar-nominated Lies My Father Told Me, David Cronenberg’s first major release Shivers, paranoid thriller Three Days of the Condor, Tarkovsky’s Mirror (Зеркало), legendary Japanese thriller The Bullet Train (Shinkansen Daibakuha), Truffaut’s unusual biopic The Story of Adèle H (L’Histoire d’Adèle H.), depressing Depression Era-drama Day of the Locust, and Márta Mészáros’s underrated family drama Adoption (Örökbefogadás).

***

For more classic film recommendations, check out our resident film critic’s “Sight & Sound”-adjacent Top 10, which includes more than a few entries from 1975.

All these movies, and more, can be rented from your local brick-and-mortar rental store Bay Street Video.