Video game art books are no longer the rarity they once were. Step into – or curbside pickup – any of Toronto’s great local shops (BMV is a favourite!) and you’re bound to find a shelf full of titles like The Game Console: A Photographic History or Press Start: The Art of Video Games. These are not concept art collections (which have been around for a while), but rather compendiums that celebrate video game art for art’s sake.

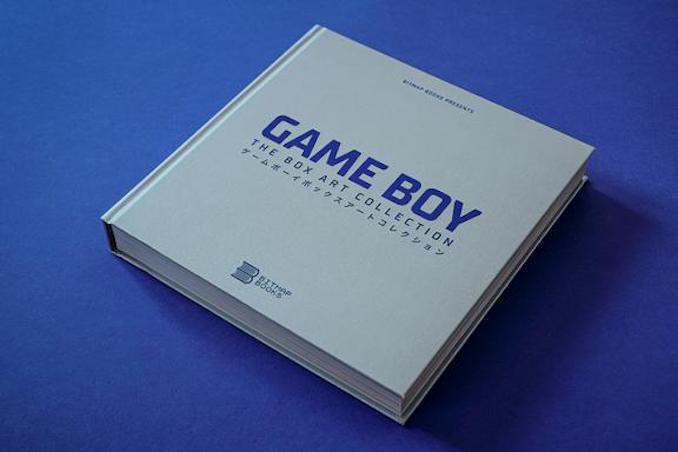

At the forefront of this publishing genre has been UK-based Bitmap Books, which, with stellar release after stellar release, has celebrated everything from SNES Pixels to The Games That Weren’t (see our review here). Its latest, Game Boy: The Box Art Collection, is, shall we say, a very specific release, catering to those who look fondly upon not the original Game Boy itself, but rather the boxes containing all its grey little cartridge games. Is this book for you? Probably not! But if you’re a geek and a nostalgist and you can immediately picture the difference between Pokémon Red and Pokémon Blue, then read on.

TETRIS AND FRIENDS

It’s safe to say that Game Boy box art has aged significantly better than the games themselves. With perhaps one or two minor exceptions (cough cough, Tetris), it’s almost impossible to revisit any Game Boy titles today. The black-and-green dot-matrix colour scheme is hard to look at in the age of smartphones and Nintendo Switches, and anything good that came out on Game Boy you can find in a better, prettier version in 2021. Even Pokémon: it’s hard to recommend the original when you have vastly superior releases, only a few years later, on Game Boy Color and Advance. (Kudos to any reader who can already rattle off the version names for each handheld).

Perhaps sensing this, Bitmap Books opted not for an 8-bit Game Boy art book, but a celebration of the way those games were packaged. And as someone who did not own an original Game Boy (I hopped on at Advance), I have to say: I’m suitably impressed. Brightly coloured illustrations pop off the page, it’s clear that thought went into making these mini-covers distinct from their NES or SNES cousins, and there’s some art here that, plausibly, could make for a nice poster.

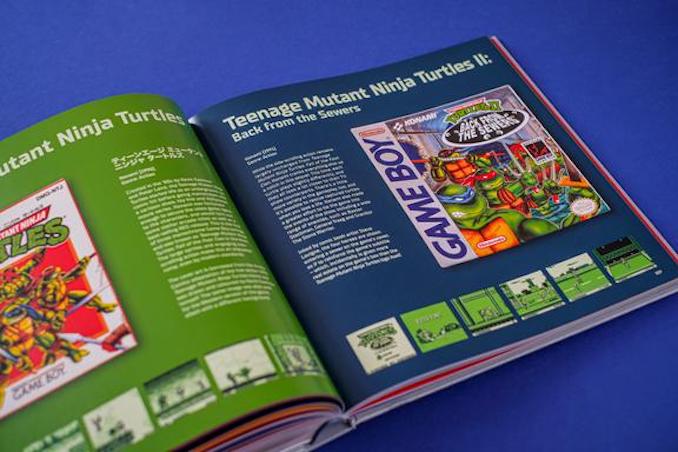

Highlights include the Castlevania/Dracula Densetsu covers, Serpent/Kakomunja, and of course the various Super Mario titles. Emphasis is placed firmly on Japanese box art, which makes sense: there were significantly more Japan-only Game Boy releases, and it’s often there that we find the most inventive illustrations. The Japan-exclusive soccer title Nippon Daihyou Team: Eikou no Eleven is a prime example – released in time for the 1998 World Cup, it features an unusual washed-out watercolour painting of two soccer players in action. Amusingly, the Box Art editors mock the package, calling it “woefully undercooked”. Personally, I love it.

LIGHTS, CAMERA?

The first twenty or so pages of Game Boy Box Art consist of essays on the history of the system and its art. The highlight is an essay by the artist known as gameboycameraman. As the photographer (real name: Jean-Jacques Calbayrac) explains, he was first inspired to use the Game Boy’s optional camera accessory, originally released in 1998, as a sort of artistic challenge: “within its limitations lives the essence of creativity and surprise.” The heavily pixelated grayscale images have a haunting quality to them, almost like stills from a lost early-90s FMV title.

The gameboycameraman interview also serves as an appropriate prologue for a book with a very niche audience. You’re here to look at and think about art from a game system that’s over three decades old. If you think it’s funny or cool that there’s a French nerd out there snapping extremely pixelated photos with that system’s camera, then you’ll probably enjoy the rest of the book.

ART AS ART

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed the Smithsonian Institute’s Art of Video Games, a nice big hardcover release with not-so-nice blurry, low-resolution screenshots. The book accompanied one of the first major exhibitions that gestured in the direction of recognizing video games as art. Unfortunately, even then, it was clear how painfully uninterested the Smithsonian’s editors were in actually treating the art with the respect it deserved. How else to explain the haphazard layout, the shoddy quality of the screenshots? Though their heart may have been in the right place, their attention to detail was not.

Books like the Smithsonian’s don’t really exist anymore. These days, when you pick up a book of Game Boy box art, you expect, and receive, high-quality images with well-edited and informative essays. Nostalgic nerds expect nothing less.

Ironically, just as game art collections have come into their own, the existence of physical video games is rapidly drifting away. Yes, you can still find store aisles where bright and garish illustrations shout out at you, calling, “It’s-a me, Mario!” But it’s been a long time since I purchased or held an actual video game in my hands – pretty much everything is digital, and sometimes I miss the old days.

Pixel by pixel, bit by bit, Bitmap Books is helping to recapture that spirit.

***

Visit the publisher website for Game Boy: The Box Art Collection here.