The Royal Ontario Museum takes on two very different photo exhibits. One commemorated the genocide in Cambodia and the other the bicentennial of the War of 1812.

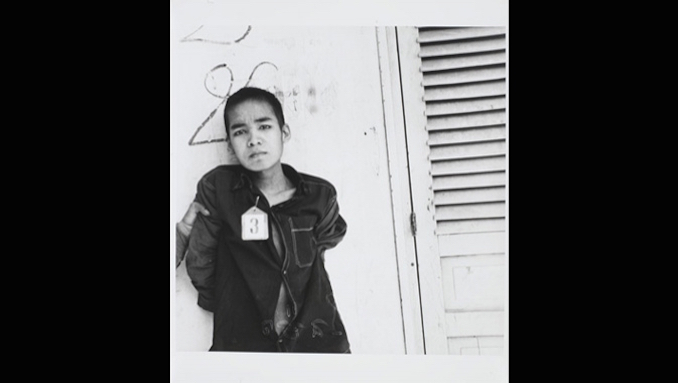

The larger of the two exhibits, Observance and Memorial: Photographs from S-21, Cambodia, is presented by the Institute of Contemporary Culture at the ROM. They feature 103 graphic prints developed from original negatives abandoned by the Khmer Rouge in 1979 at the S-21 prison in Phnom Penh. The exhibition sheds light on the atrocities that occurred under the Khmer Rouge regime from 1975-1979 and how Cambodia is recovering from those events today. It also forces us to consider human rights issues on a global perspective while acknowledging that those traumas still exist today.

As to the purpose of Observance and Memorial, Francisco Alvarez, Managing Director at the ICC at the ROM explains, “These events in Cambodia’s history are not well understood by the Canadian public, as they followed so closely on the heels of the Vietnam War, which at the time dominated North American media.” The Khmer Rouge rose to power and enforced their view of a utopian agrarian society. What followed was years of mass killings of those opposing their rule. Observance and Memorial focuses on S-21, one particular prison that, between 1975-1979, held 14,000 people captive. Once Vietnamese forces invaded Cambodia and brought down the regime, only 23 people managed to survive, five of which were children.

Following the timeline laid out displayed, from the rise of the regime and Pol Pot to the fall, we see Cambodia facing horrors that were never mentioned in our history books. That of course may be because the Khmer Rouge was only officially dissolved in 1999. But what does this mean for us as Canadians? We have heard the term “genocide” being used to describe what happened in Rwanda and during the Second World War but we often forget what it truly means: the murder of several individuals. Through the display of these photographs of prisoners in S-21, Observance and Memorial removes the anonymity of mass murder. While we do not know the names of most of the people pictured, we can now see what these victims looked like and know there were innocent men, women and children interrogated, tortured and murdered. The significance of these events sink in once you come to realize that you are looking at pictures of the dead and that they were only a fraction of the regime’s “purging.” As Alvarez says, “…we present these photos not as examples of photographic art, but as documentary evidence. This is not an art exhibition.”

Today, the former S-21 prison serves as the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and is among the most visited sites in Cambodia. The ROM exhibit is all the more significant now as a result of the remaining surviving members of the Khmer Rouge awaiting trial.

Observance and Memorial: Photographs from S-21, Cambodia is on display until March 10th, 2013 in the Roloff Beny Gallery.

While the fourth floor of the ROM documents the events in Cambodia, the first floor’s Sigmund Samuel Gallery of Canada houses a very different way of using photography as documentation.

Commemorating the bicentennial of the War of 1812, the ROM presents Afterimage: Tod Ainslie’s Vision of the War of 1812. Burlington-based Tod Ainslie travelled throughout eastern North America between 2001-2009 documenting historical sites from the War of 1812. Ainslie used three pinhole cameras that he designed and built himself to take several photographs, of which the ROM has acquired twenty-two. These images, in black and white, are meant to portray the historical sites as they would have seemed in 1812, had the chemical for developing these pictures existed then. No people are present in any of the photographs and the shadows both around and in the images give them an eerie look, like following a ghost walk.

Since the war did occur 200 years ago, it’s clear that many of us may feel disconnected from it only knowing what actually was in our history textbooks. Ainslie however, by not including people in his images, actually portrays loss, absence and quiet through these empty spaces. While the images look very much like they were taken in the past, Ainslie has carefully constructed and developed these photographs for this desired effect. The exhibit explains Ainslie’s aesthetic choices as well as which pinhole camera he used for each image. Of the process, Ainslie says, “As I worked with these primitive cameras and saw the images they produced, I felt a strong sense of the period’s aura, a sense of the places themselves, and an empathy for the people whose energies created them.”

Afterimage: Tod Ainslie’s Vision of the War of 1812 is on display now until February 24th, 2013 at the Royal Ontario Museum.