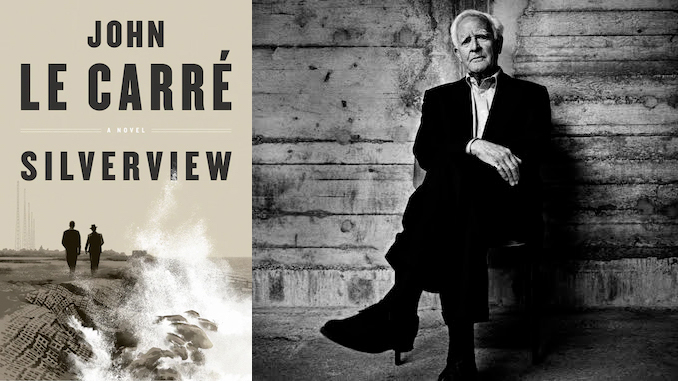

The spectre of death hangs over Silverview. Not just that of the novel’s central figure, an ex-spy dying of cancer, but also that of Hiroshima and Srebrenica and Auschwitz, and of untold and forever nameless spies, and, unavoidably but perhaps not inadvertently, that of the novel’s author, the late John le Carré. Whether le Carré knew he was dying when he wrote Silverview is hard to say. But he was certainly old, and fading – he died at the age of 89 last December – and the thought must have been near to mind.

Death has always been a theme in le Carré’s spy novels, the best of the genre. He knew better than anyone that espionage is a nasty business of disposable bodies. But rarely has death been so central, or so painful.

I AM BECOME DEATH

Silverview‘s inciting figure, Deborah Avon, does not appear until about halfway through the novel, and then only briefly. Avon is dying, has been for some time, and only lately has decided to reveal one last secret to her former comrades at MI6. It’s this decision that sets in motion the events of the novel, even if Deborah herself only fleetingly, if rather memorably, appears in a single chapter.

The nature of Deborah’s secret is not nearly as earth-shaking as others that swirled around le Carré’s past works, though it embodies familiar themes: loyalty, righteousness, pride. Though unspoken, it’s implied that she is driven by a desire to die with as clean a conscience as a career in espionage might allow her.

Complicating matters is the presence of her very alive husband, Edward “Teddy” Avon, something of a gadabout who has recently inserted himself into the life of a bookseller named Julian Lawndsley. Teddy is at best a rake, at worst a con man who Lawndsley spots immediately and falls for nevertheless. (In certain respects, Teddy reminds me of George Smiley‘s old pal, the very charming yet very sleazy Toby Esterhase.)

But it’s Lawndsley, the bookseller, who is Silverview‘s actual main character, yet another of le Carré’s innocent protagonists dragged into a complicated web they have no hope of comprehending. Unlike past protagonists, however, Lawndsley is about as far removed from a traditional hero as one gets. He’s middle-aged, not particularly fit, and spends the novel restricted to the confines of a small, seaside town in East Anglia. In this respect, he’s a far cry from heroes like Jonathan Pine in The Night Manager or Charlie in The Little Drummer Girl, both of whom become active participants in the spy game at great personal risk. About the most dangerous thing Lawndsley gets up to is spying on the impressive and foreboding Silverview manor, which lends the novel its title and from which most of its dramatic momentum originates.

THIS MORTAL COIL

I’ve made no secret of my love for le Carré, who I contend is the greatest spy novelist of all time, with the possible exception of Graham Greene. There are very light shades of Greene in Silverview, in particular his Brighton Rock, with its comparable seaside setting and interest in questions of Christian guilt. But whereas Brighton Rock, and Greene, were Very Catholic, Silverview is set in the prim, proper, Protestant world of English espionage. Everyone dresses well and speaks with a cultivated accent (especially those with ambiguous origins, like Teddy Avon), and for these characters the very idea of getting their hands bloody is anathema. There’s a reason why le Carré’s greatest character, George Smiley, is a pudgy middle-aged man who doesn’t carry a gun: in le Carré’s universe, the nasty bits of espionage are best left to other, less refined (and more disposable) players.

That’s why it’s so interesting that Silverview is also very much concerned with specific, bloody acts, and their lingering, bloody, legacies. Obviously, the history of espionage is a history of death, and Silverview is far from the first le Carré novel to ask us to care about the death of spies. But Silverview also contains interesting connections to the Holocaust, to the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, and to the struggle for Palestinian freedom. It’s no coincidence, then, that one of Silverview‘s main non-Silverview settings is an abandoned British nuclear base. Yes, Silverview is about one dying spy, but it’s also about the many, horrific, nearly inconceivable ways that people dream up for killing one another.

Silverview‘s plot is one of the simplest and least confounding in le Carré’s oeuvre. Julian Lawndsley, ex-City trader, has moved to a quiet seaside town with dreams of opening a bookshop. By chance – or is it? – a man claiming to be an old acquaintance of his father’s offers to help whip the bookshop into something more interesting, a “Republic of Literature.” Meanwhile, MI6’s Head of Domestic Security, Stewart Proctor, has received a letter containing a damning revelation, one that doubles as a personal embarrassment as well as a professional one. The cast is small, narrow, the only other characters of consequence including the Avons’ daughter Lily and a handful of Deborah’s old connections from the Service. In what may be a first for a le Carré, there is zero in the way of globetrotting: Deborah Avon may have been a top agent with a fascinating and well-travelled CV, but the novel is set entirely in the UK.

WHAT DREAMS MAY COME

Looking back on the long arc of le Carré’s career, it’s interesting to see how he moved from stories about the specific – individual pawns in a greater Cold War game – to the general, using individual characters to make a broader comment about whatever theme he was pursuing, whether the arms trade (The Night Manager), Big Pharma (The Constant Gardener), or Brexit (Agent Running in the Field). Silverview is nominally about an unassuming English bookseller who lives down the road from a dying ex-spy. But it’s also about big, scary systems that cause and perpetuate violence across the globe, from Gaza to rural Bosnian villages and all the way back to WWII and the terrible crimes on both sides of that conflict. It’s not that le Carré was ever blind to these systems, and indeed his very first novel, 1962’s Call For the Dead, deals directly with the Holocaust – something that’s occasionally overlooked in career retrospectives. But le Carré at 89, putting the finishing touches on Silverview, was a different, angrier, man compared to the young MI6 agent David Cornwell, who had to conjure up a pseudonym when he wrote Call For the Dead.

In Silverview, we see not just le Carré’s anger, but his despair and his frustration about the barbarities committed in the name of geopolitical interests. We see that anger echoed by a few of the novel’s key characters, all of whom are, in one way or another, driven by a need to take action for the dead (or dying). This includes, rather tellingly, Silverview‘s “antagonist”, whose belatedly revealed motivations garner sympathy on a level not seen since Call For the Dead.

Silverview was more or less complete when le Carré died, the last of his novels and a wonderful posthumous gift to readers. Still, there’s little doubt that further incomplete works will make their way to us, the author’s son Nick Harkaway intimating as much in Silverview‘s afterword. That’s fine, and I’m sure the Tolkien Family Trust has some good tips. But it’s too bad that, in the face of climate change, anti-vaxxers, and the general embrace of the idiotic, we’ve now lost le Carré’s keen mind and righteous pen.

Deborah Avon is dead. George Smiley is long gone. And there will never be another John le Carré.

***

JG

Visit the official website for Silverview here.