In 1912, the needs for a subway system in Toronto were first brought upon the city through an independent survey. This survey was intended to gather information on the citizens’ view towards existing traffic conditions, and was submitted with the purpose of proposing new changes and developments to improve the current issue of Toronto traffic. Upon consulting with the report, engineers came to the conclusion that soon, surface transportation would reach its limit of carrying capacity and efficiency. After that limit was reached, they proposed that a subway system would become both convenient and economically ideal.

This estimated capacity that would soon render the streets of Toronto irreparably clogged, was primarily due to the original street measurements carried out according to the British chain measurement of 66 ft. While this width in pavement may have once been sufficient for the languid carriage rides of British folk making a trip into the city, it was simply not compatible with the heavy flow of rushed and irritated driver’s of Toronto’s modern day.

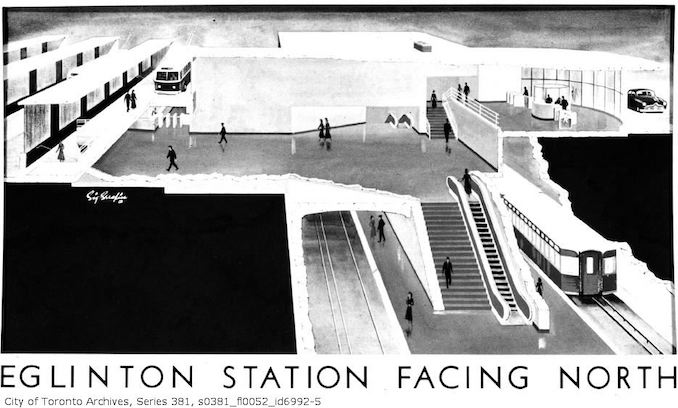

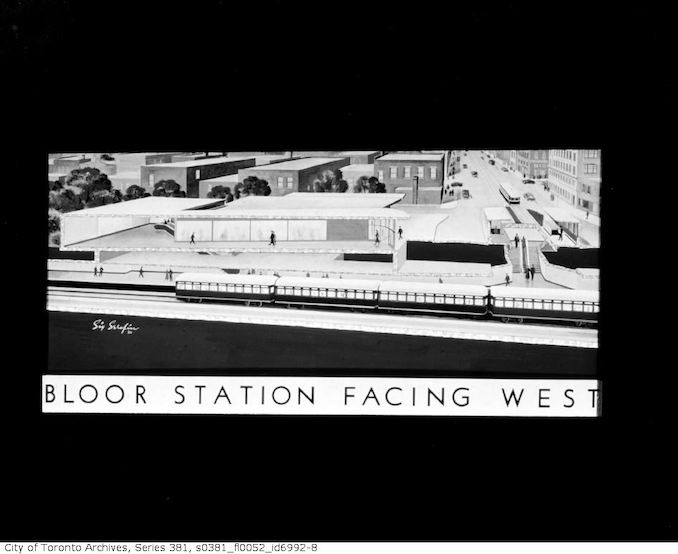

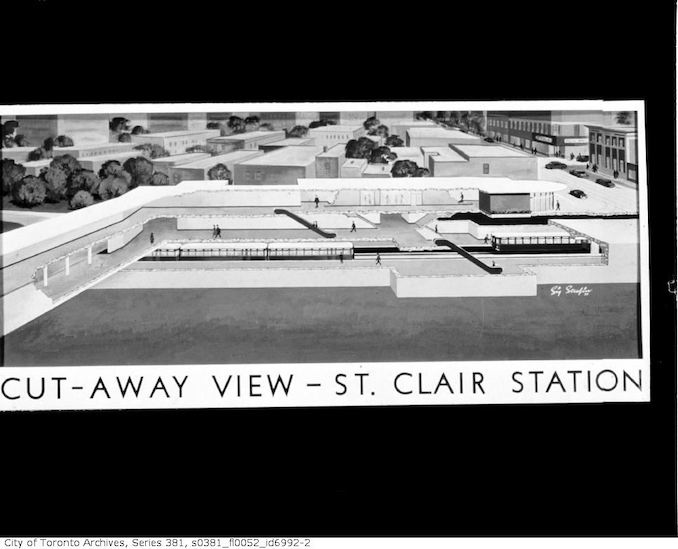

In 1943 the initial preliminary sketches and blueprints were first drawn up for what would be the heart and centre of the system, Young Street subway station. Thus in January of 1946, after receiving an enthusiastic rubber stamp from the citizens of Toronto, the subway system’s construction officially commenced having received a 10 to 1 in vote in its favour.

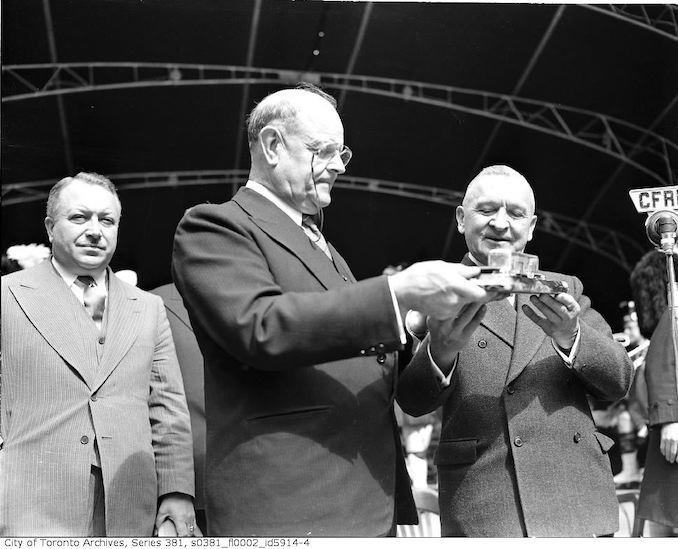

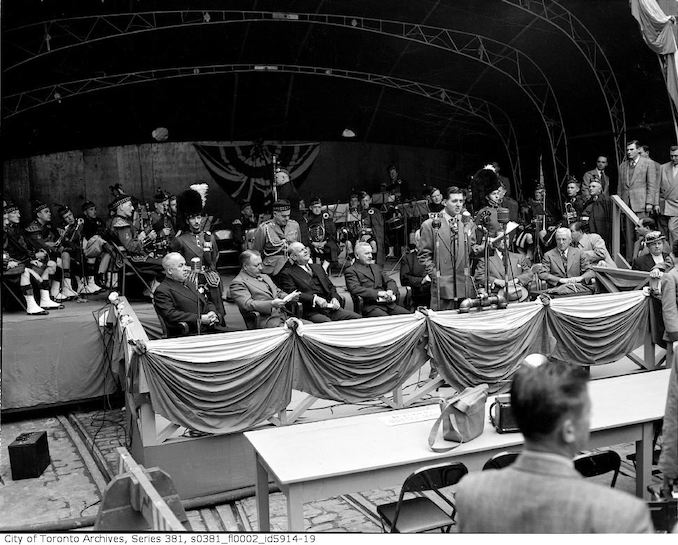

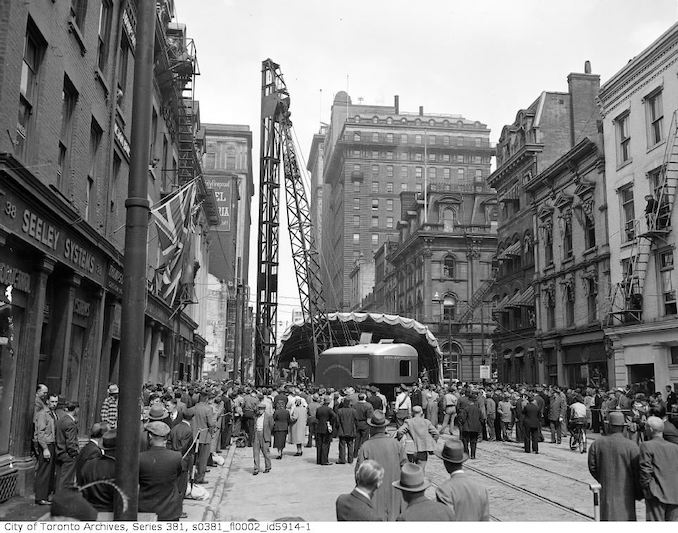

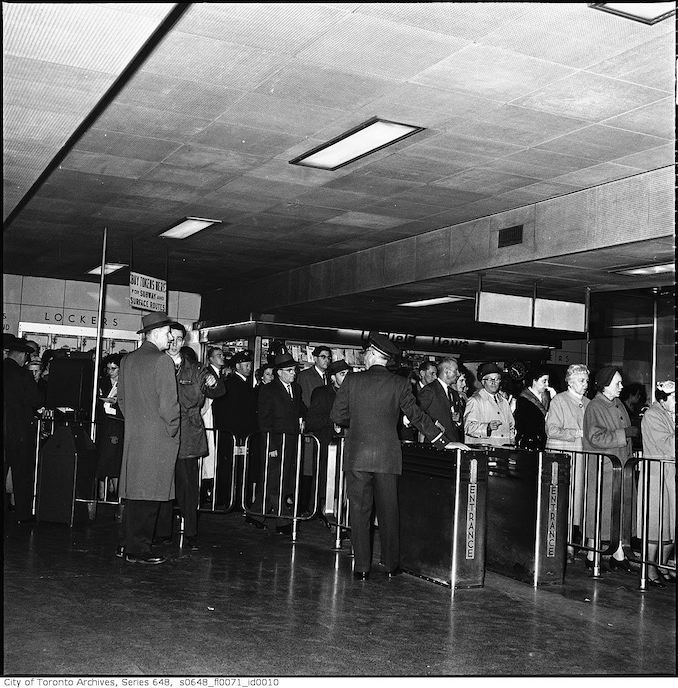

The city burst out into booming celebration that summer. A festive shrill flowed jauntily from the orchestra’s bagpipes and politicians of the city made optimistic speeches with wide grins cast across their faces. With a meager 400,000 people at the time, compared to today’s almost 3 million, the city began to feel slow rumblings beneath their very feet, which would soon lead to the long and labouring process that would serve them with tremendous growth as they neared the 21st century.

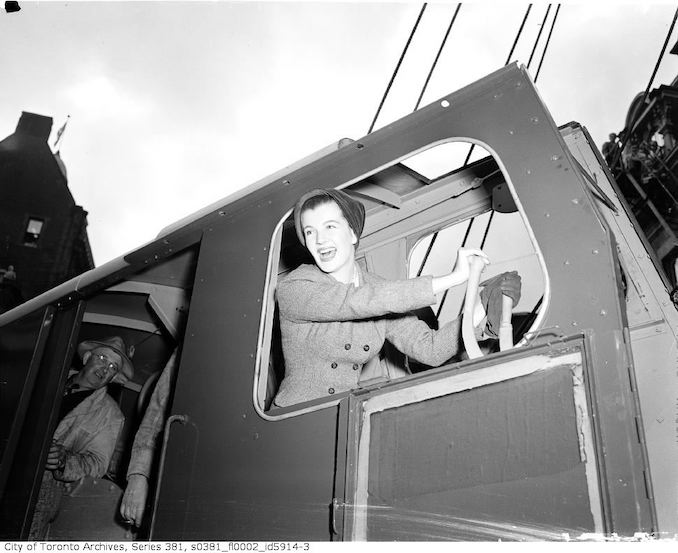

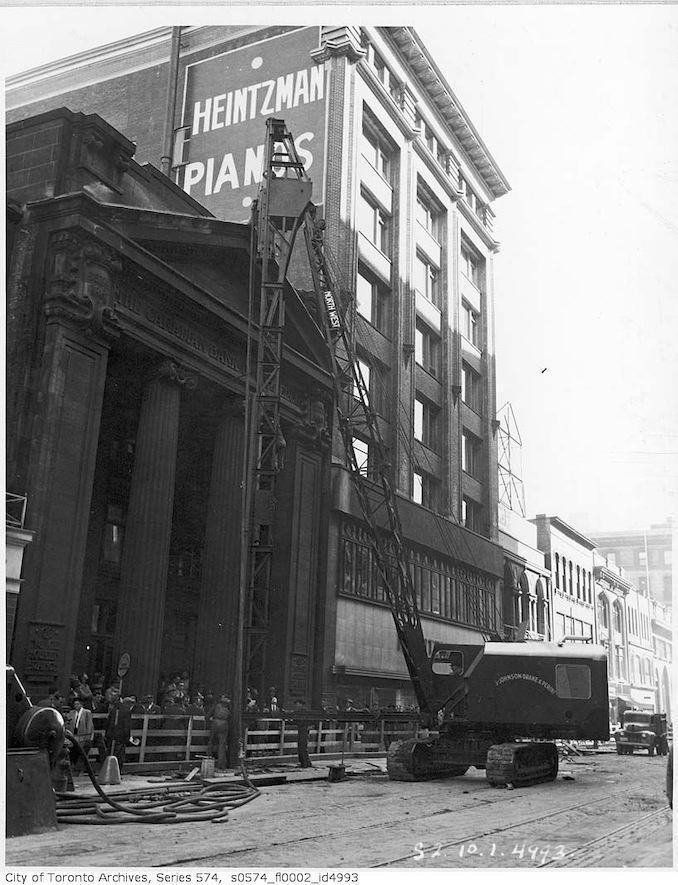

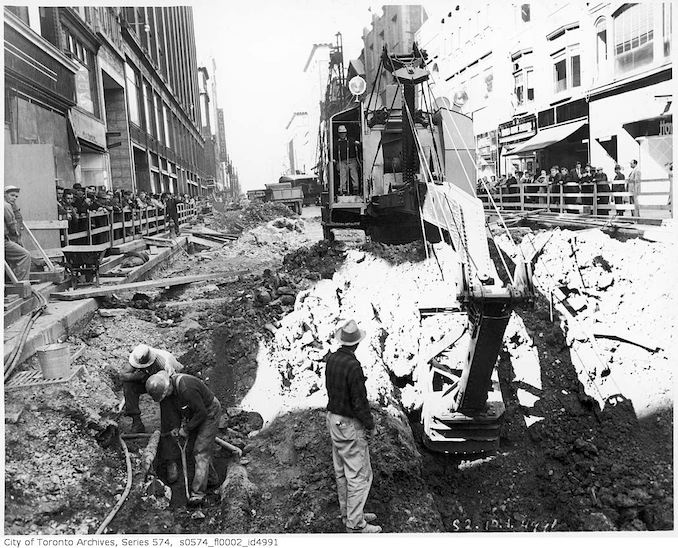

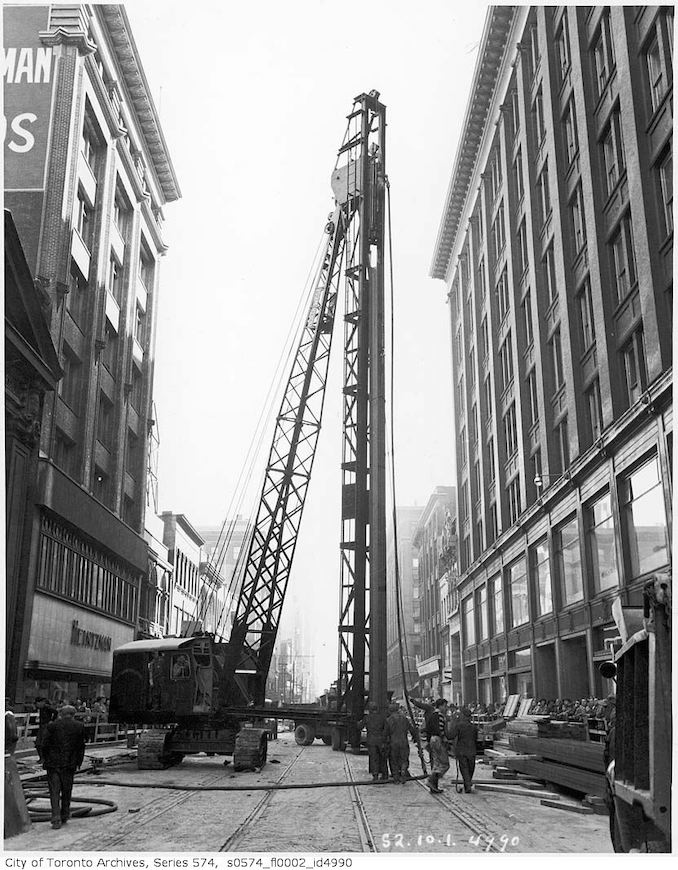

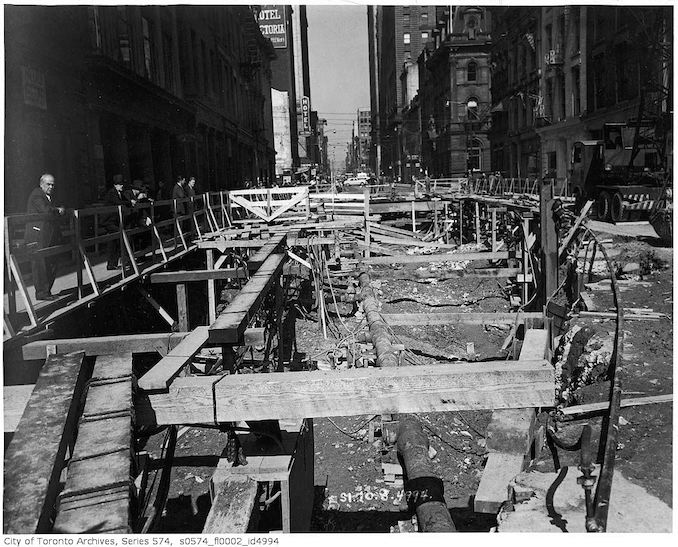

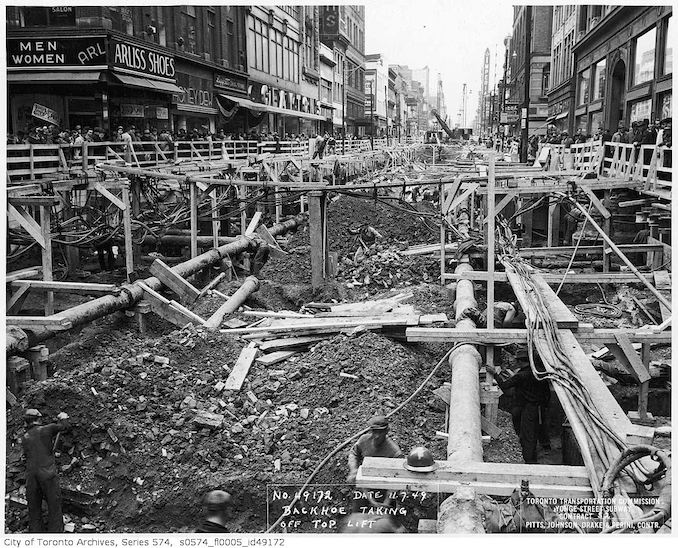

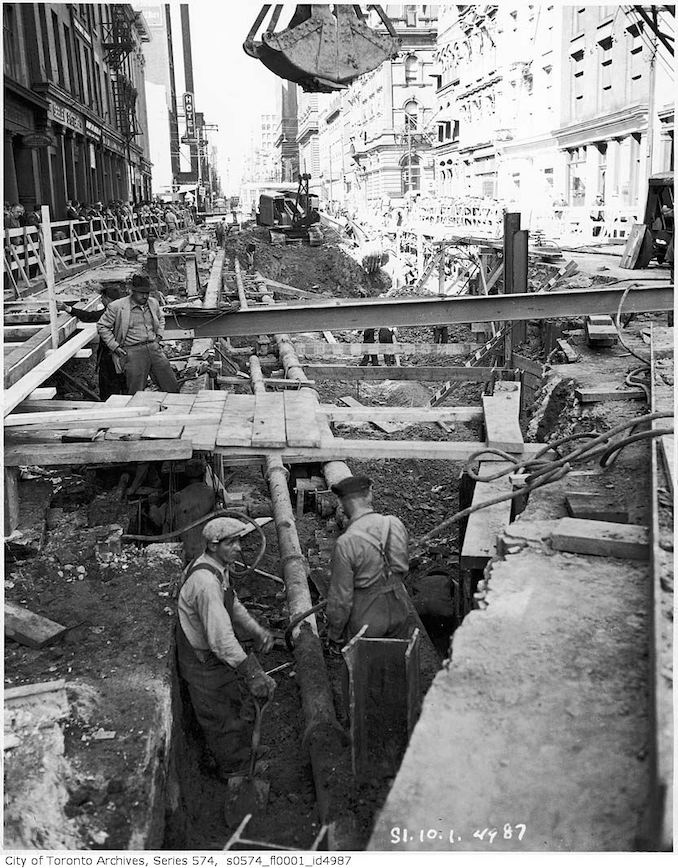

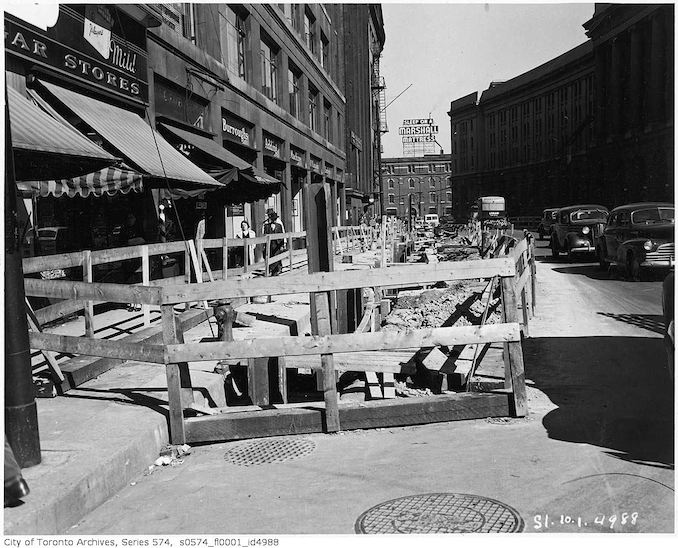

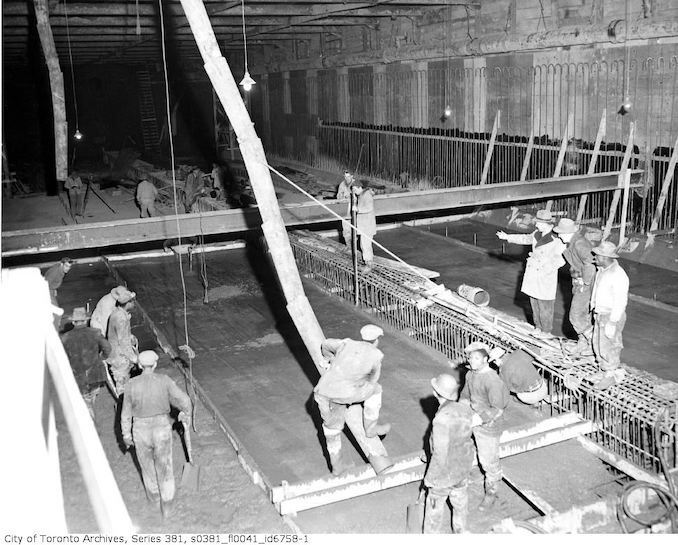

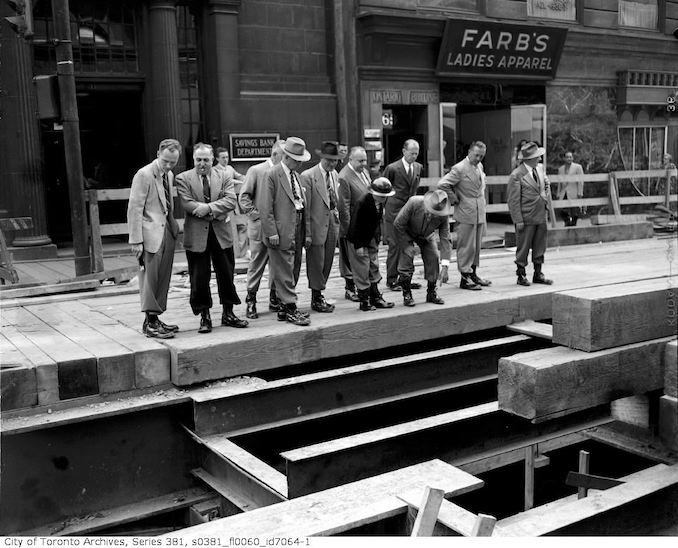

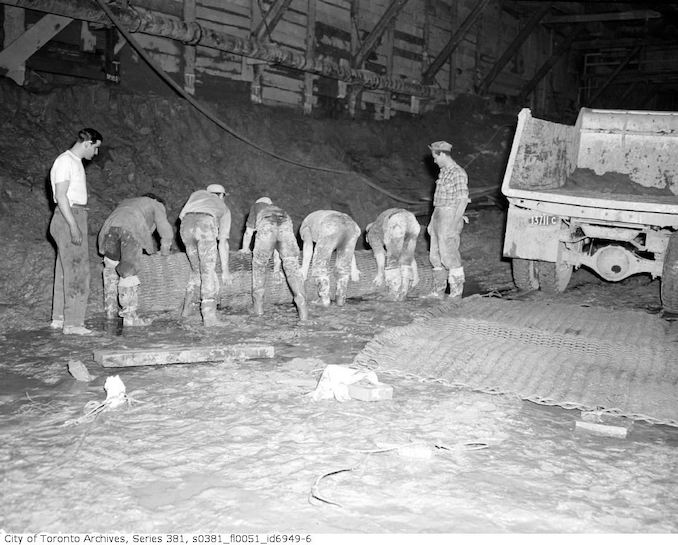

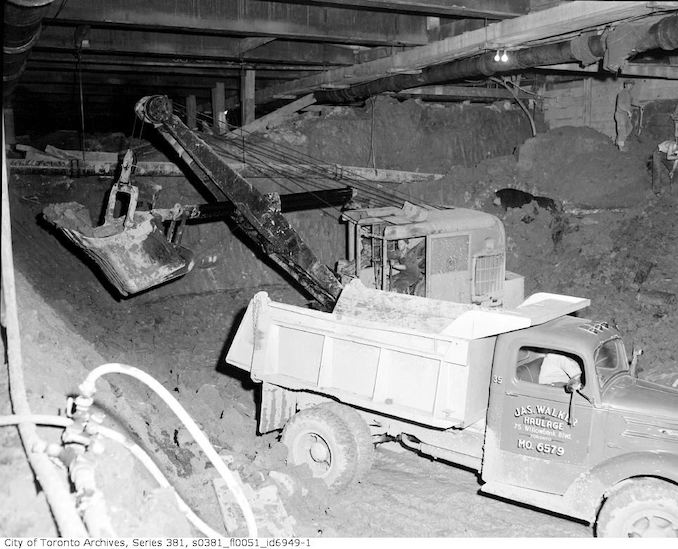

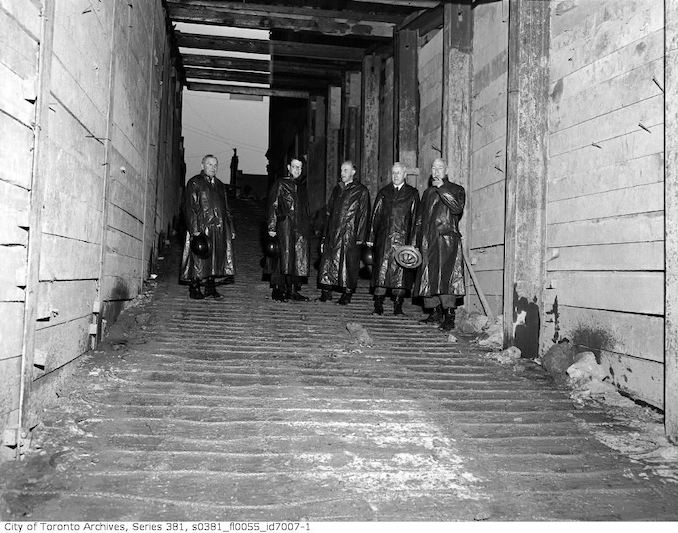

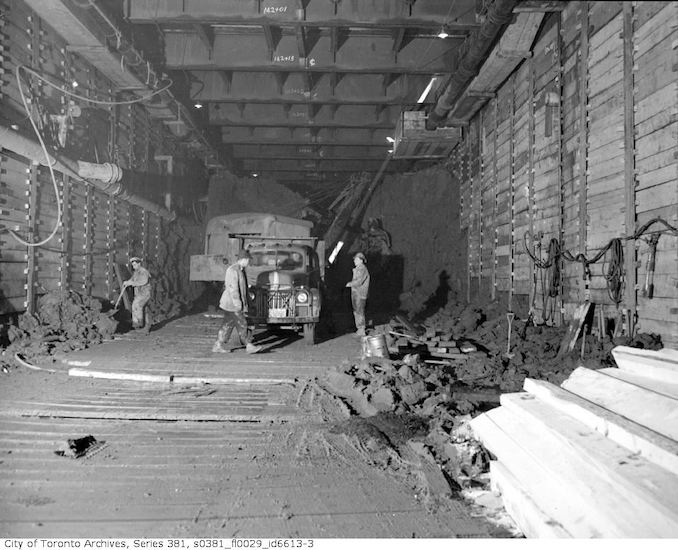

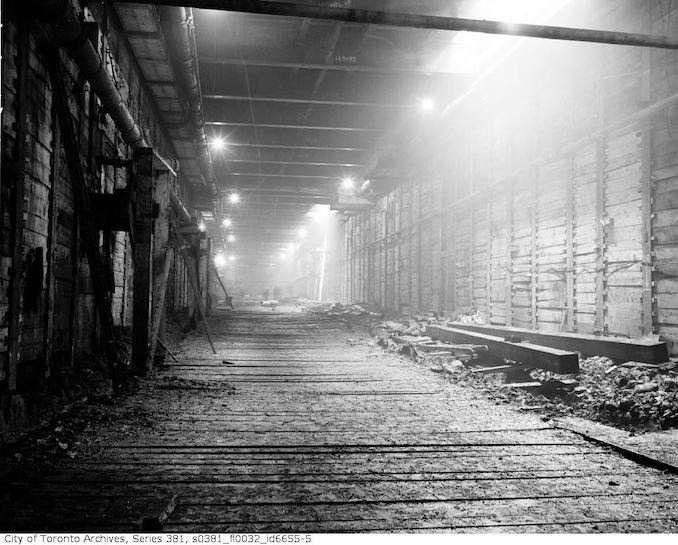

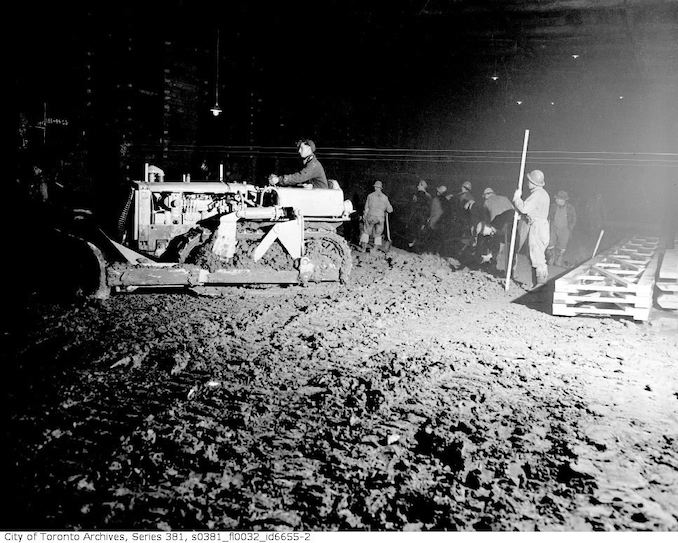

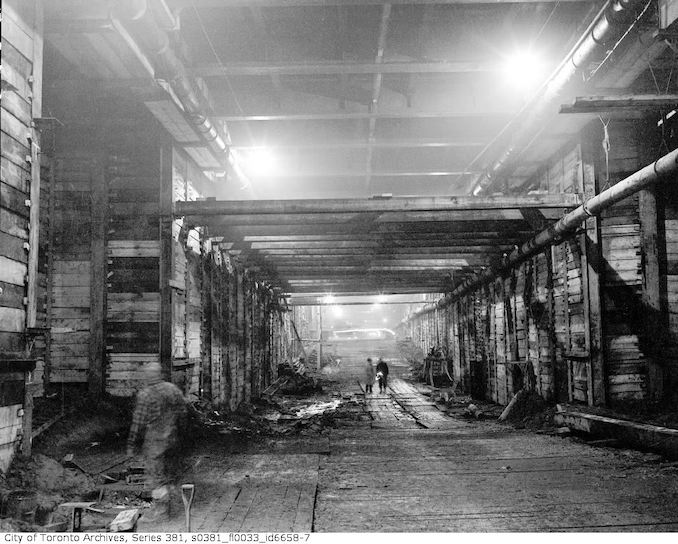

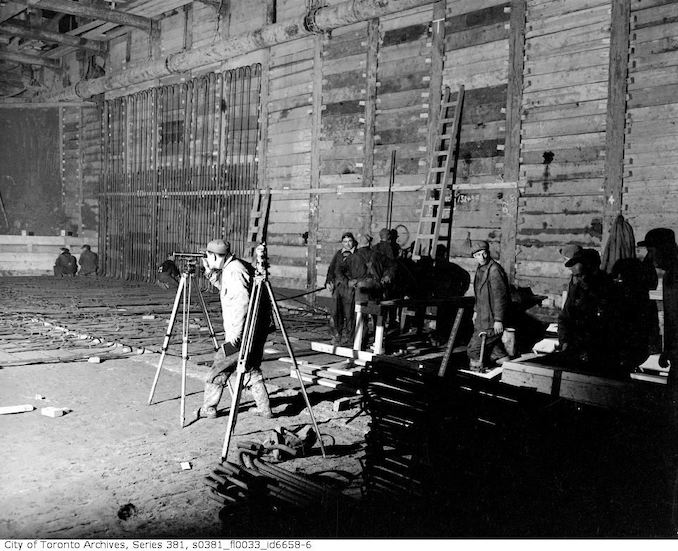

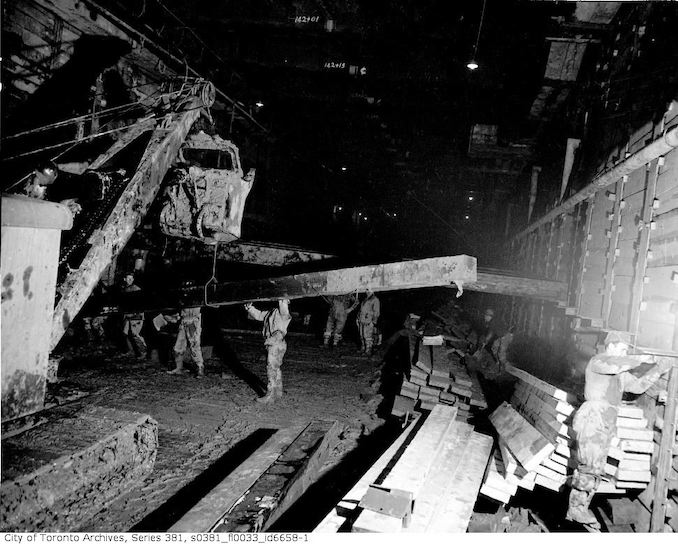

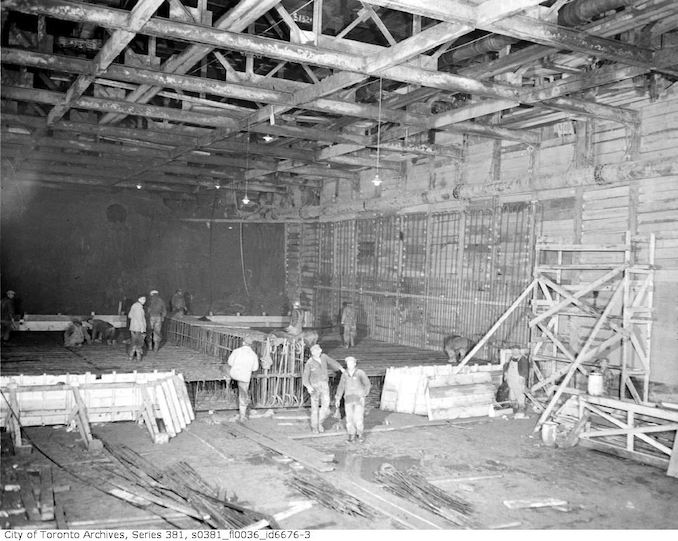

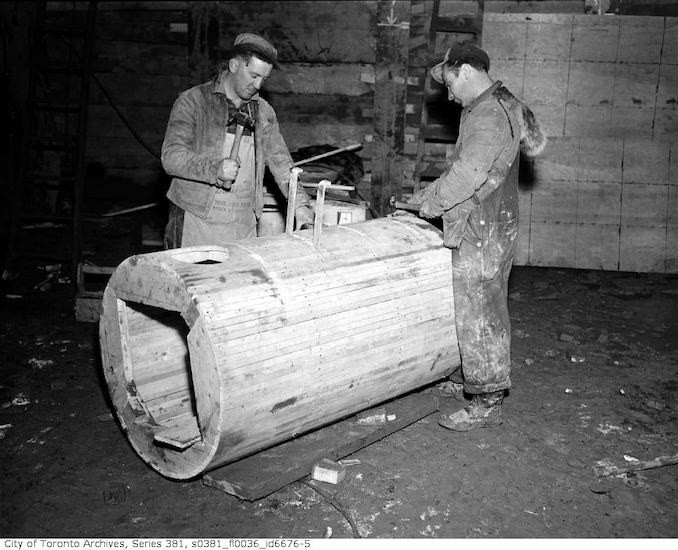

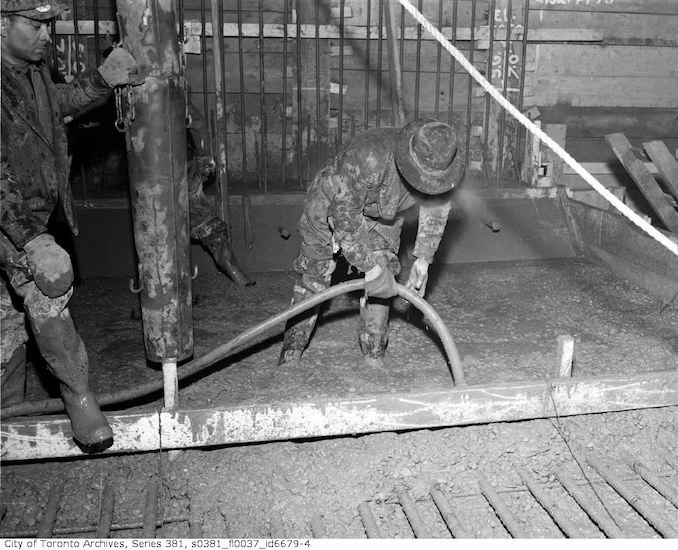

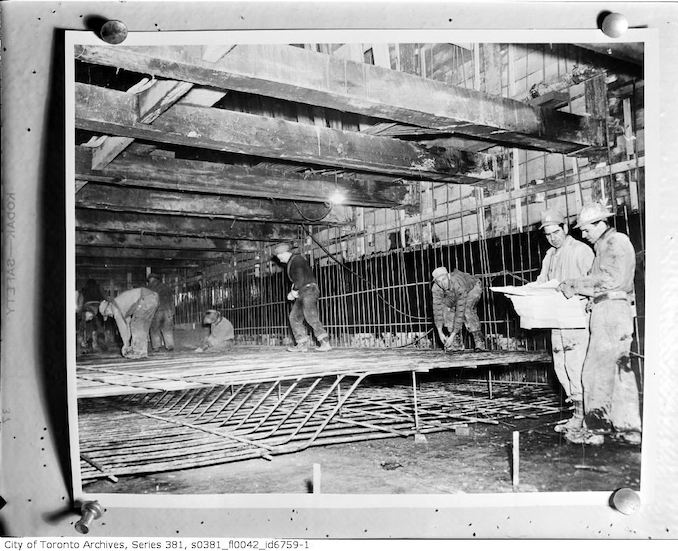

As with any new change, an air of mystery and curiosity was blanketed over the city. The blaring drilling of the machinery and the sweeping skyline of colourful cranes spanning across the office building windows was a promise of glitz and glamour that undoubtedly kept the public intrigued. While the esteemed men, complete with tin hard hats and official orange jackets, proudly endured the arduous work that left them panting in the sweltering summer heat, the citizens of Toronto found great pride and entertainment in the new urbanization of their city. The public was so fascinated in fact, that a new group of “sidewalk superintendents” cropped up, composed of everyone from hurried business men to jovial children to leisurely women in hoop skirts from all walks of life who would fill up the sidewalks with glee and excitement. As if they were pressing their noses up against the glass at a sports arena, they would marvel at the grand excavations and innovations that were taking place right in front of them, forming colourful and exuberant teeming crowds around what seemed like the most dramatic transformation the city had ever seen. One particularly invested member of the enamoured citizens even began their own popular publication, which regularly ran editions centred around describing and delivering the progress of the subway’s construction.

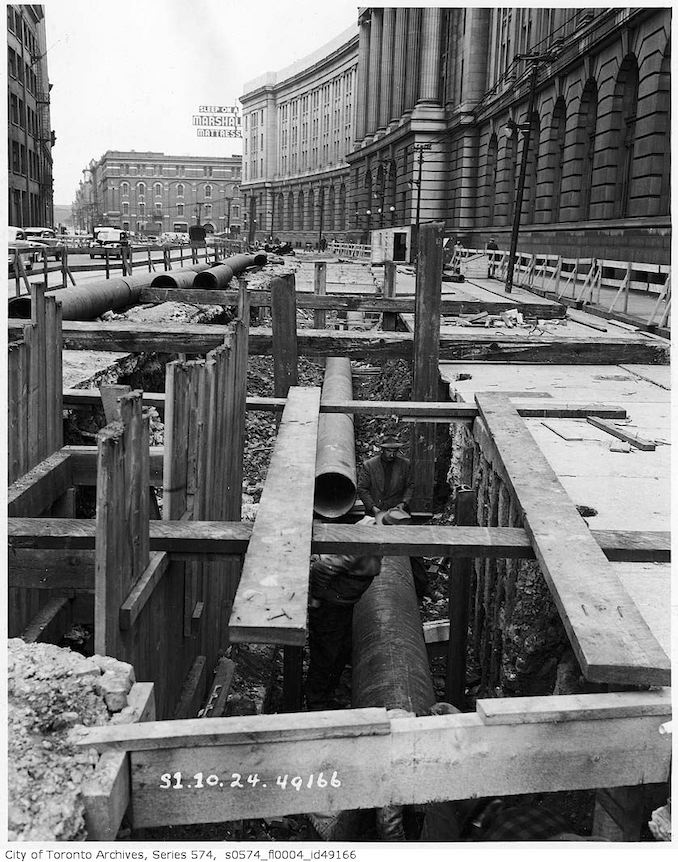

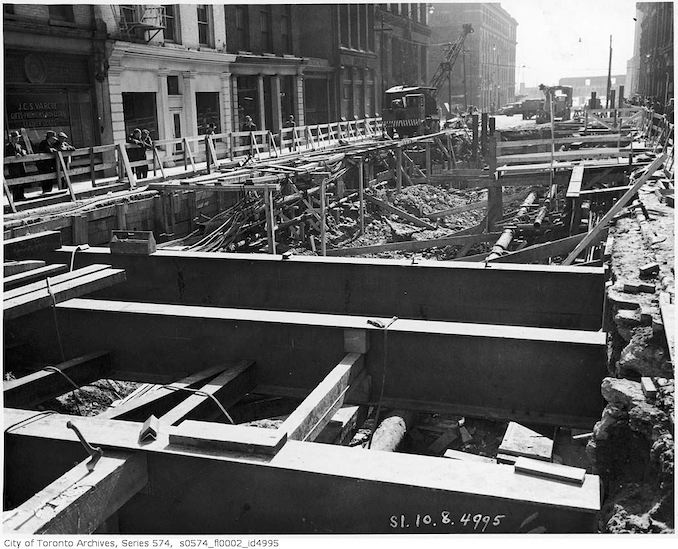

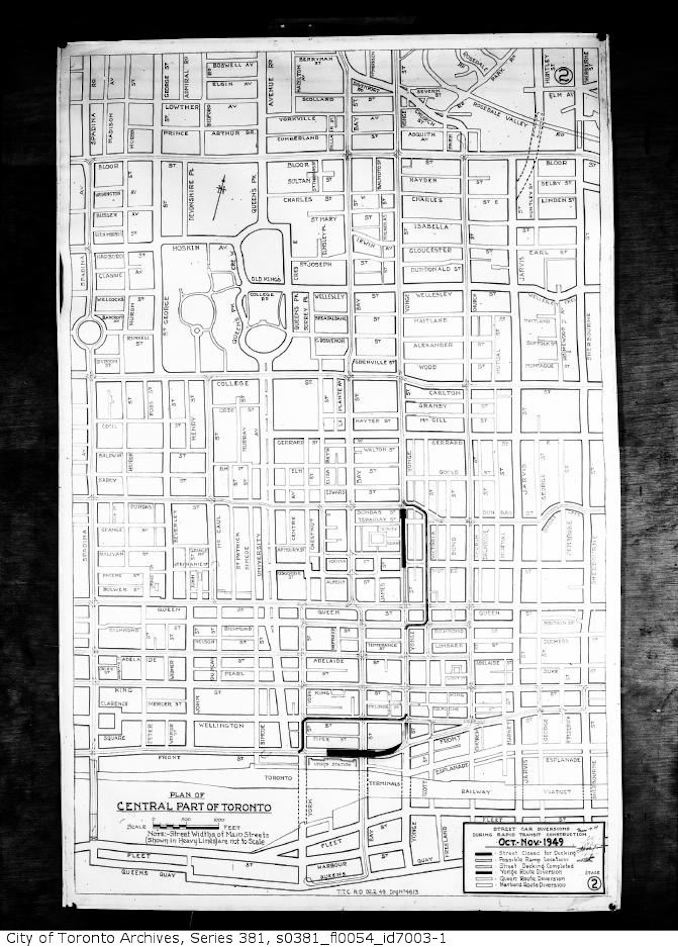

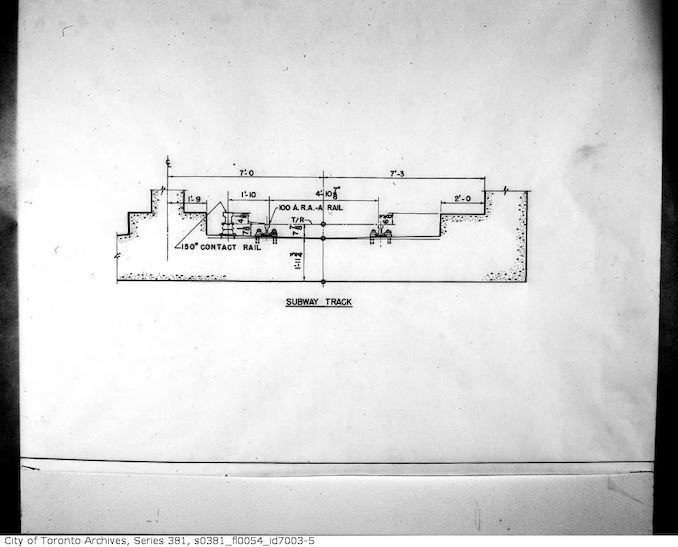

Even with the tremendous excitement and overwhelming support from the citizens, the job was draining and brain wracking. Throughout the 5 years of continuous construction, engineers of the highest calibre were busy rapidly studying the logistics of transit systems, planning and preparing for the proposed route of each train. While this took place mostly behind the scenes and not in the way of the average citizen’s view, it was certainly vital in the construction of the well honed system that we can all ride with ease today.