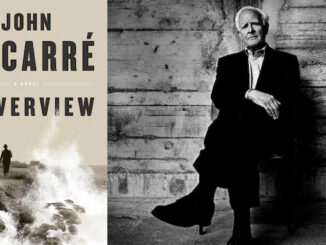

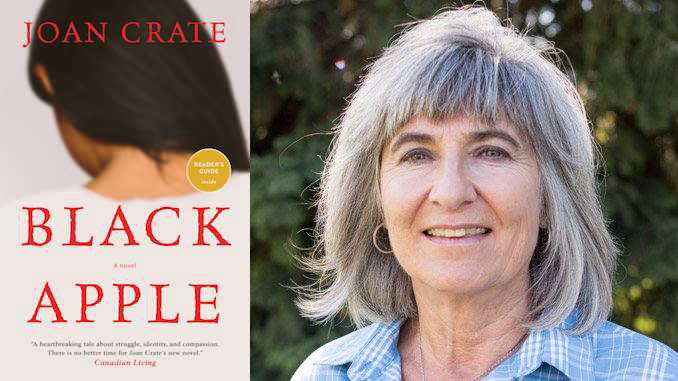

This week I had the pleasure of diving into Black Apple, an award winning debut novel by indigenous author Joan Crate. I was initially nervous about taking on this novel because it deals with an extremely controversial aspect of Canadian history—residential schools—but Black Apple handled these issues remarkably well.

Black Apple is the story of a Blackfoot girl who is taken from her family and delivered to St. Mark’s Residential School for Girls. Renamed Rose Marie by the nuns who run the school, Sinopaki must adapt to the Christian world.

Sinopaki encounters many terrors at St. Mark’s, beginning with the beatings administered by Sister Margaret. Crate describes many real, physical terrors that were heavily documented in residential schools: malnutrition, cramped spaces, rapid spread of disease, and abuse of all kinds.

Others horrors are spiritual, including the ghosts who reveal the school’s gruesome past. These ghosts haunt Sinopaki day and night for years, and over time she’s able to piece together their stories.

What really impressed me about Black Apple was its ability to be honest about the trauma residential schools caused and still make the nuns sympathetic characters. Most of them honestly believe they’re doing the right thing by “civilizing the Indian”. They believe the church is inherently good.

This stuck out to me because often our natural instinct is to demonize abusers, particularly abusers in religious orders. We do this because it’s easier to believe only monstrous people can be abusive, but the truth is much more complicated than that.

I found this approach to residential schools to be a breath of fresh air. A setting like a residential school makes it easy to slip into gratuitous violence, but every moment of physical contact in Black Apple is written with specific intent. Crate doesn’t shy away from these complications. Rather, she encourages the reader to face them. The amount of time given to physical and sexual violence is extremely limited, forcing us to face the true horror of residential schools: the very idea of “civilizing the Indian.” This approach brings the issues Sinopaki is already facing in her mind into the real world.

Sinopaki herself is also a wonderful character, and it was fascinating to watch her grow into a woman. Her journey is riddled with sadness and fear, but her spirit refuses to be crushed. This strength of spirit is what carries her story to a satisfying conclusion, despite the many challenges she faces.

Black Apple is an honest examination of the many issues surrounding Canada’s treatment of indigenous people, and I believe this makes it particularly important in the wake of Canada 150. Our government would rather we forget about residential schools and the lasting impact they’ve had on our indigenous people, but Joan Crate successfully brings these issues to the forefront.

If you’re looking for a powerful book that will make you think deeply about our country’s history, give Black Apple a shot.