Punchdrunk Theatre’s Viola’s Room is both alike and unalike the company’s mask shows in interesting ways.

Long-time readers will know we’re huge fans of Punchdrunk’s loosely interconnected “mask trilogy”, of which you can read more about here and here, and of which we consider last year’s The Burnt City to be the apotheosis not only of the Punchdrunk brand but of immersive theatre in general.

Long-time readers may also know that, after The Burnt City, it was unclear where Punchdrunk would go next, given the palpable risk of self-plagiarism and/or iterating itself into oblivion. At one point, there was talk of a collaboration with Pokémon GO creators Niantic, though that fell apart after what sounds like years of tantalizing experimentation.

As it turns out, Punchdrunk’s first production since City shuttered in September 2023 is the smaller, more intimate, if no less stylized Viola’s Room. We’re going to do our best to refrain from too many direct comparisons with the mask shows – Viola’s Room is simply offering something different, on a different scale, and with different goals in mind – but readers should know that, taken in its own right, Viola’s Room is an interesting experiment, if not quite what you might be expecting.

In some ways, Room acts as proof of concept; evidence that Punchdrunk has intriguing ideas about working on a smaller scale. Which, in fairness, is where the company started out some twenty-four years ago.

Viola’s Room really is small: small in scale, small in scope, small in duration (45 minutes), small in production requirements (only one performer, and then only a pre-recorded performance), and small in capacity: the maximum number of guests permitted in any one time slot is six people. (A nice knock-on effect of all this is that the tickets are quite affordable.)

Ideally, you’d gather six friends to “own” your time slot, though we did enjoy chatting with the strangers we were paired with, making for a more social experience than the anonymous, hundreds-strong audiences of the mask shows.

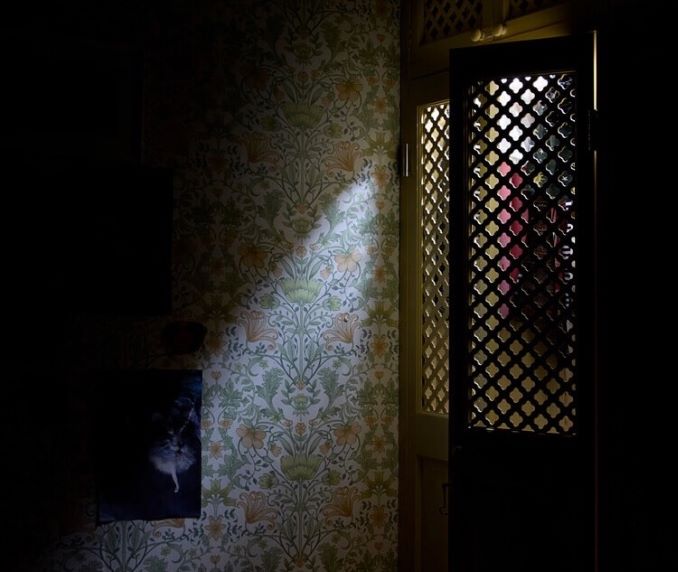

Every performance of Viola’s Room is the same, and it goes like this: six audience members are handed headphones at their dedicated entry time. A brief explanation follows – don’t try to adjust your headphones, do “follow the light” (an imperative which is not explained, but whose meaning soon becomes apparent) – and then all six are led into the title room itself. Viola’s room is where this story begins and where it ends, an intricately and meticulously designed space put together by the award-winning Punchdrunk team. As is our wont, we’ll leave it to our readers to discover that space for themselves, though you can get a feel for it in the publicity stills included here.

There are no live performers in Viola’s Room. Instead, the story is told entirely through voice-over by an unnamed narrator (Helena Bonham Carter, at her finest). Each audience member, so far as I can tell, hears the exact same story on their headset, though I suppose it’s possible my friends and I heard slightly different versions without realizing it.

The story – well, this would be far too spoilery to delve into here – but suffice it to say that, like its predecessors, Viola’s Room melds the contemporary with the mythical, telling a story that is at once literal and allegorical. Did I mention you’re in bare feet the entire time?

Viola’s Room‘s storytelling ideas are marvellous, the emphasis on light and sound in the absence of actors ensuring that every environmental detail, every word uttered by Bonham Carter, earns your complete attention.

Moving from room to room (and yes, there are several rooms, including the types of liminal spaces – tunnels, hidden passages, and the like – which Punchdrunk is known for), you’re never more than a few steps away from the next thrilling moment. Though the story, per se, is told through voice-over narration, it’s also fair to say the story is told by the environments themselves: the sights, the sounds, the textures, even the scents.

Much like prior Punchdrunks, there’s a carefully curated soundtrack – to give you a flavour, it includes both The Cranberries’ “Zombie” and Seal’s “Kiss From a Rose” – which will have more or less impact on the listener depending on which decade they were born in. The production design reflects an equally impressive attention to detail, with certain props and locations taking on additional meaning as the story unfolds, and in some cases circles back on itself. Viola’s Room would not work without its audio, just as Bonham Carter’s narration would be less compelling if it didn’t relate and respond to the physical space through which you move.

Viola’s Room is also maddeningly opaque. The story you hear often seems quite detached from what you’re seeing or doing, particularly in those moments when the show introduces an artificial sense of urgency, whisking you through spaces and images that pass by too quickly to be properly understood.

Similarly, some of the coups de théâtre (and there are a few which will make you gasp) appear to have been included more because Punchdrunk could, not because the story demanded it. At the end of our journey, not a single member of our group could explain what it all meant, even if we were impressed by it all.

That was true for Viola’s predecessors, of course, but then they had the advantage of adapting the familiar. Sleep No More is a Shakespeare riff which relies on audiences having some familiarity with one of the Bard’s greatest works. The Burnt City was a fairly faithful reimagining of the Trojan War, infused with stories from Greek mythology, with Punchdrunk even providing a complete character breakdown on a chart in the opening hall. With The Drowned Man, Punchdrunk eventually began handing out short plot summaries before each show, having realized that audiences were far less familiar with the source material, Georg Büchner’s unfinished 19th century play Woyzeck.

That Viola’s Room is an adaptation is not made clear whatsoever, and I only learned of its source – a relatively obscure 19th century short story which I tracked down in rather dubious form on wikisource – during a casual chat at coat check. Punchdrunk would do better to upload the story to their website, and/or make it clear there’s more to Viola’s Room than simply the 45 minutes we’re allotted.

Viola’s Room is too short and too obscure to elicit the kind of emotional response which Punchdrunk veterans might be hoping for. (For what it’s worth, I cried at the end of Sleep No More the first time I saw it.) On the other hand, Viola’s Room is also just short enough that it never feels overwhelming, and its linearity – you are guided quite clearly from Point A to B to C – winds up being more of a strength than a weakness, ensuring its moments of theatrical magic are experienced by all. (Something which was by definition impossible in the free-roaming mask shows.) Impressively, Viola’s Room can also, in rare moments, induce a sense of fear and panic, proving that linearity is no obstacle to surprise.

I like the idea of Viola’s Room perhaps a bit more than I liked the show itself: not every immersive show needs to be gargantuan and labyrinthine, and not every immersive show requires a cast of dozens (or really any cast at all) in order to tell a compelling, if only sporadically moving story. These are things that I probably knew before visiting Viola’s Room, but it took Punchdrunk’s latest experiment to prove the company can deliver a great show without all the bells and whistles it’s better known for.

Assuming Punchdrunk keeps doing these quieter, smaller affairs, my only suggestion is that they offer audiences a bit more by way of explanation – provided they can do so without losing that sense of awe and, yes, bewilderment which we have come to expect.

To paraphrase Homer Simpson: it was brilliant… I had absolutely no idea what was going on.

***

Visit the website for Punchdrunk’s Viola’s Room here. On now through December 2024.