Industrial Architecture

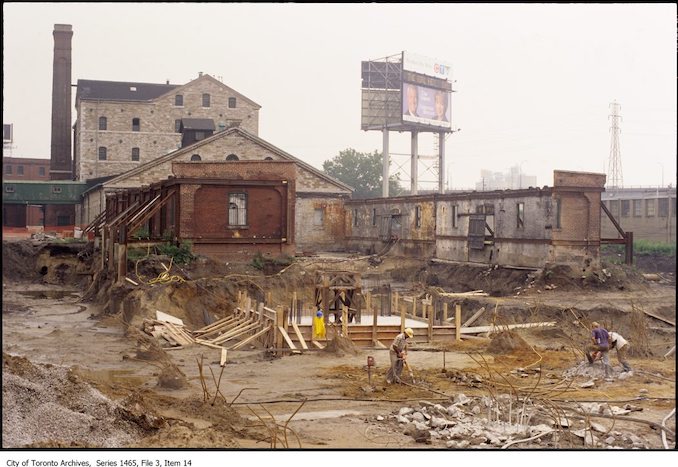

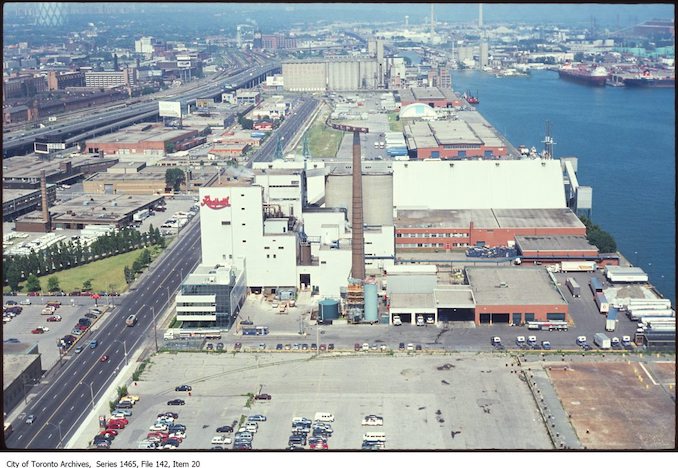

The main factor of Toronto’s early prosperity in the nineteenth century was its harbour, the port serving as a trading spot for materials. Surrounding factories such as Gooderham and Worts whisky distillery, Massey Ferguson’s farm equipment factories and the Redpath Sugar Factory were the main suppliers, occupying the bulk of the downtown. Thus, the majority of Toronto’s settlement and architecture was situated on the waterfront, explaining the southbound locations of our most historically significant landmarks today.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Toronto’s connection with other cities became heavily dependent on railways. Therefore, industrial areas developed around the freight lines, in areas such as Weston and East York. In the late 1900s deindustrialization came into full effect, phasing out the majority of older waterfront factories by 1990. Some of the historic industrial buildings were then converted into lofts and office spaces, and many were demolished to construct dozens of condominium towers along the lakeshore to expand housing for Toronto’s ever-growing population.

Residential Architecture

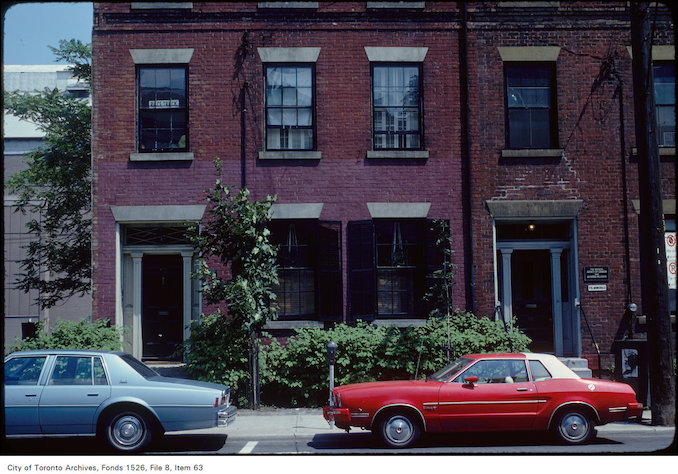

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the Georgian style dominated the preferences of elite Torontonians building homes. This style was especially favourable among Toronto’s wealthy population, explaining the abundance of Georgian style homes in neighbourhoods such as Rosedale and the Bridle Path. The Georgian style of homes can be characterized by their rigid symmetry in building mass as well as window and door placement, red and brown brick, stone, stucco, hip roofs, and window decorative headers. This style remained popular among the Loyalist-dominated Upper Canada predominantly due to its British connections, where it had ironically fallen out of style by this time, but remained current in Toronto until the 1850s.

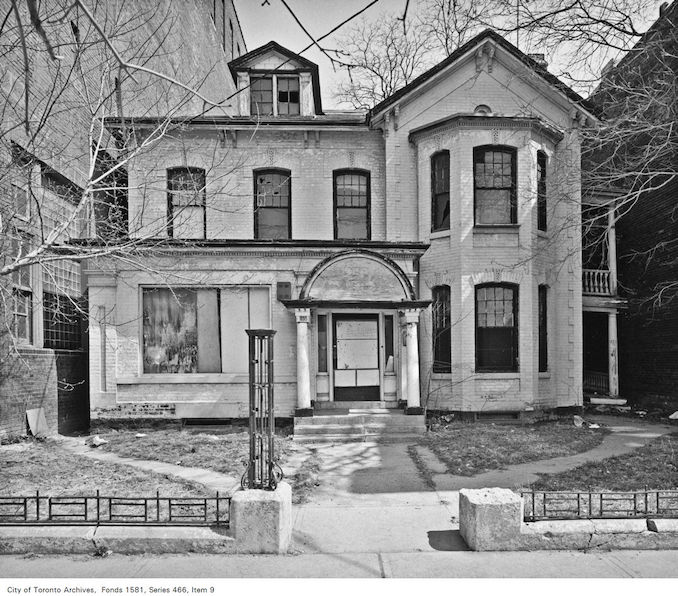

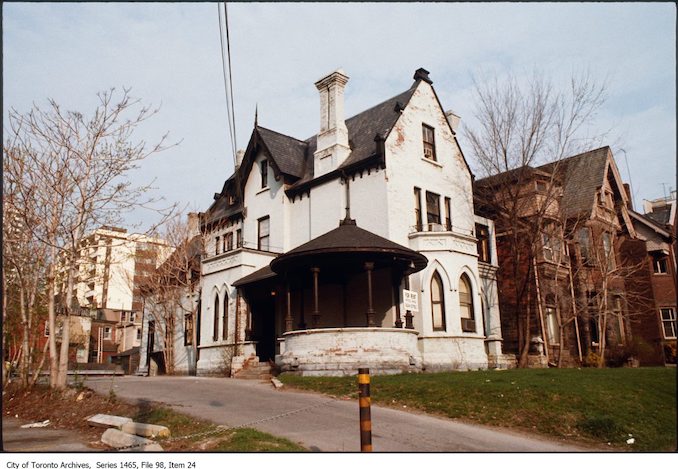

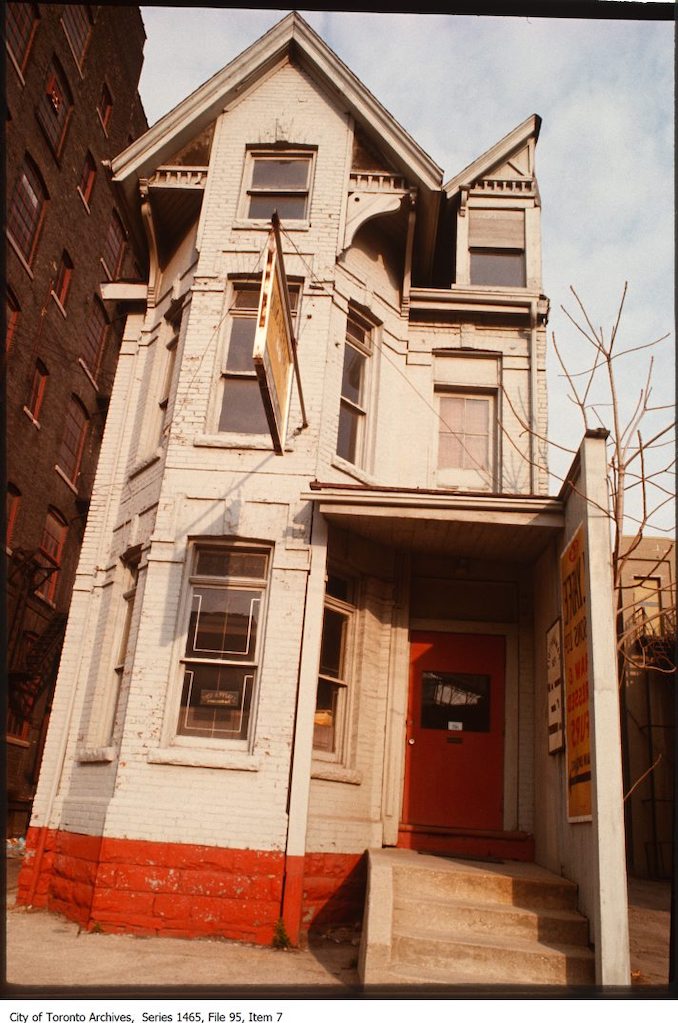

In the late nineteenth century, Toronto welcomed the rise of Victorian architecture, as well as many of its revival styles. This style of architecture was thought to be more modern, unique and creative than its successor, characterized by steep gabled roofs, round angles, towers, turrets and dormers, shapely bay windows, stained glass, centric carved woodwork, and bright coloured paneling. This style lent itself well to narrower lots, and thus Victorian style housing is most abundant in the city’s traditionally middle-class neighbourhoods where individual properties were smaller, most notably Cabbagetown, Trinity-Bellwoods, Parkdale, and The Annex. These neighbourhoods hold some of the largest collections of Victorian houses in North America. Specifically houses constructed in the Annex developed an individual iteration of the Victorian style, called the “Annex Style House”. This style contained a variety of diverse and eclectic elements borrowed from many different styles. Most distinctively, these houses are built of a mix of brick and sandstone, turrets, domes, and decorative ornamentation.

Commercial Architecture

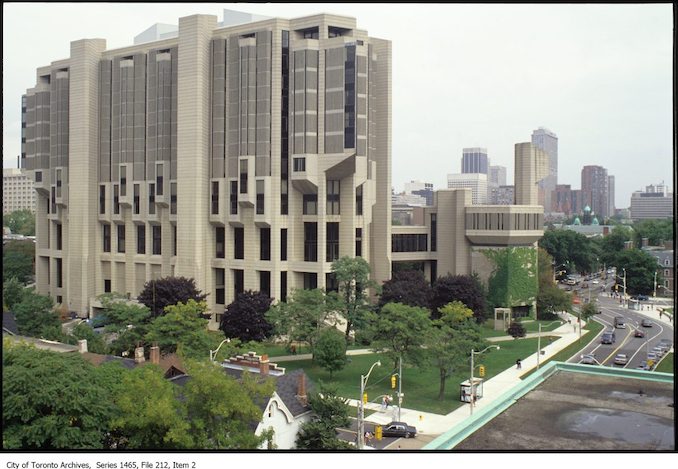

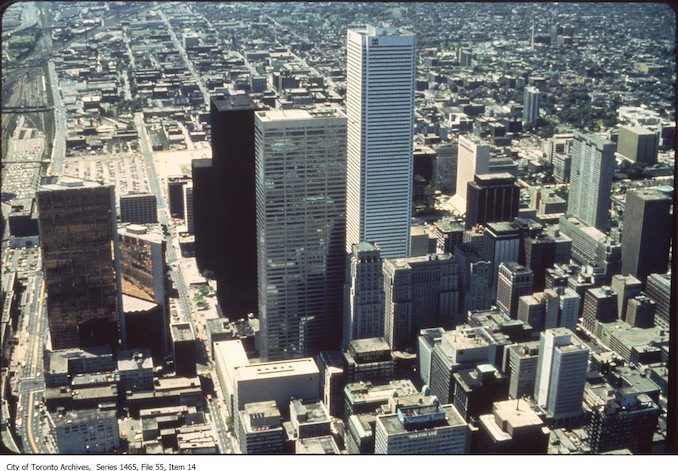

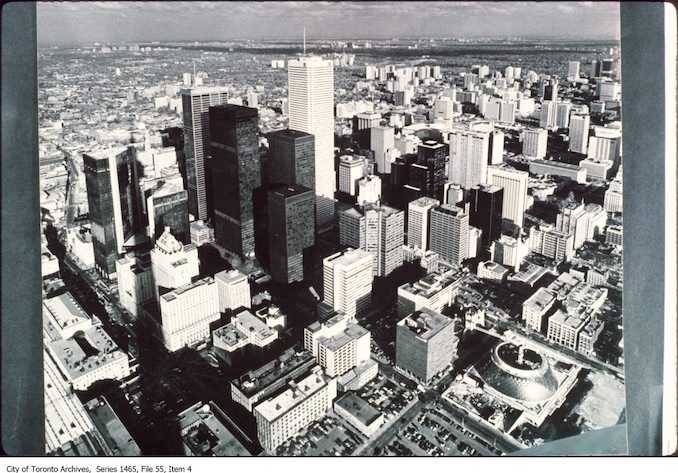

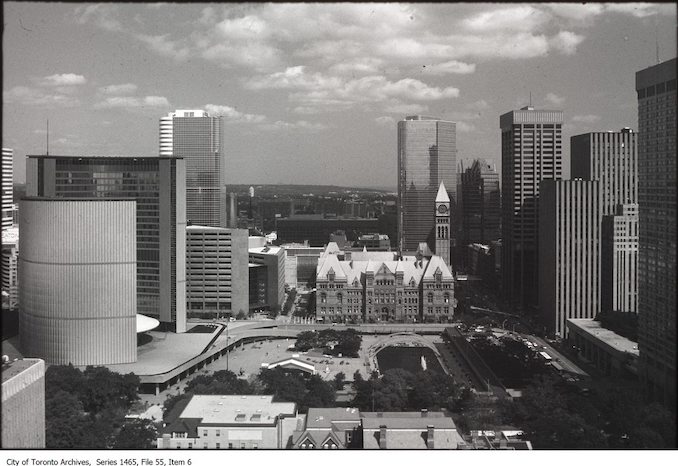

The surge of commercial architecture came during the beginning of the deindustrialization period, when the majority of factory work took place overseas and office work was increasing in the city. Toronto has since blossomed into the metropolitan centre of Canada, and thus many of the country’s largest firms are based here. Among Canada’s oldest and most prominent firms are the Big Five banks, all of which are located in the Financial District, which is centred on the intersection of Bay Street and King Street in the heart of downtown Toronto. The Financial District is home to the most clustered, tightly packed buildings in the city, resulting in its sky-scraping towers at every turn. Southwest of Bay and King is Mies van der Rohe’s Toronto-Dominion Centre, a compound of six black International Style towers. From 1967 to 1972, its tallest tower was crowned the city’s first modern skyscraper and was the tallest building in Toronto.

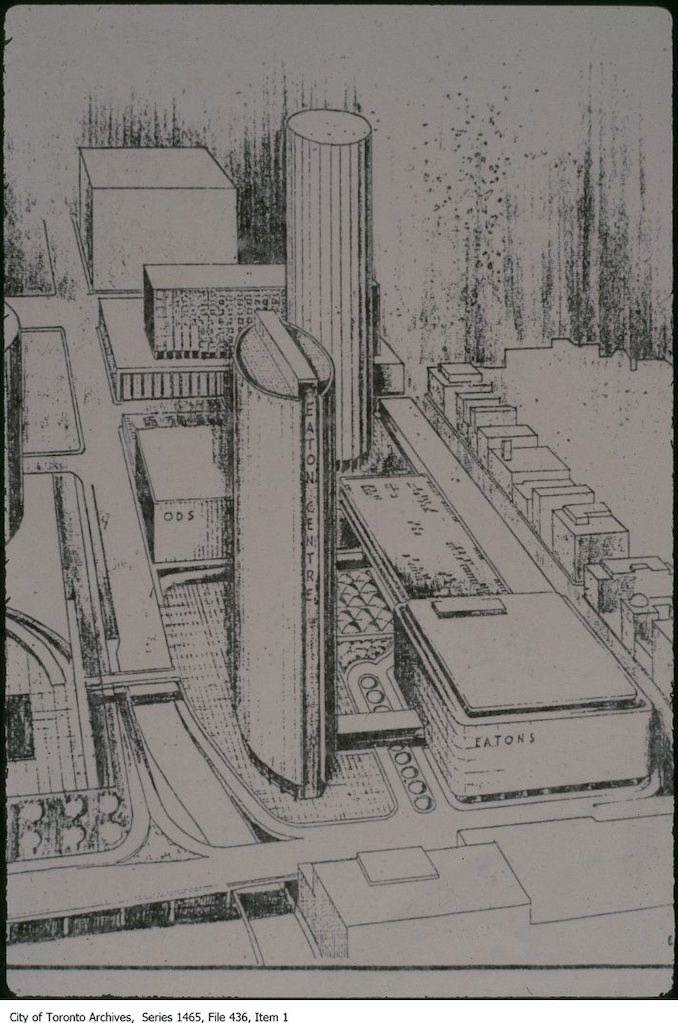

Toronto also led the surge in commercial shopping in Canada, giving rise to one of North America’s first downtown shopping malls. Designed by Eberhard Zeidler, the Eaton Centre was designed as a multi-levelled, vaulted glass-ceiling galleria, modelled after the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan, Italy. At the time of its opening in 1977, the interior design of the Eaton Centre was considered quite revolutionary and influenced shopping centre architecture throughout North America. Since the 2010s, the Eaton Centre is the most visited tourist attraction in Toronto and the most visited shopping mall in North America.

Institutional Architecture

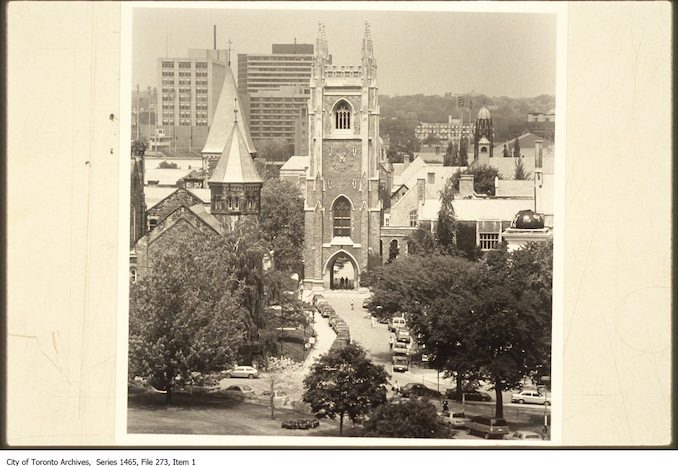

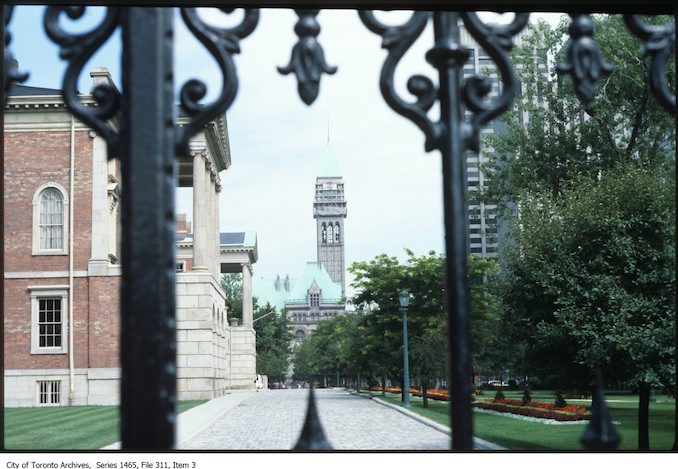

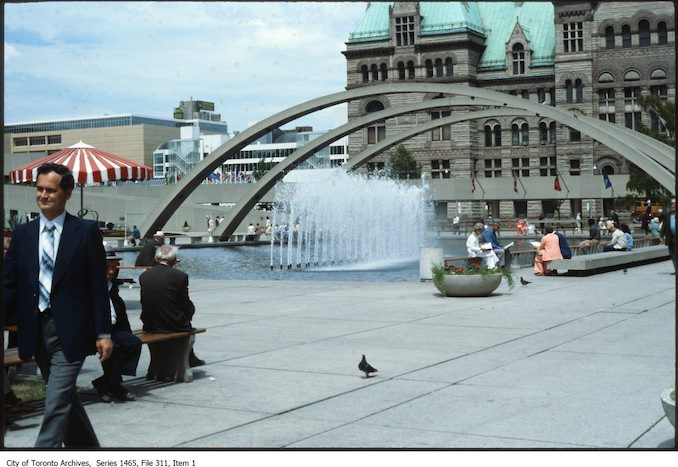

Two of the most distinct and well-known structures in downtown Toronto are the old and current city halls. The Old City Hall was built in 1899 and is a classic example of the late Victorian Romanesque Revival style. This style is characterized by rough-faced (rusticated) square stones, round towers with cone-shaped roofs, columns and pilasters with spirals and leaf designs, and broad “Roman” arches over arcades and doorways. Across the street is the new Toronto City Hall (opened in 1965), which bears a stark contrast to the Old City Hall. The reflective and brazenly modern design was composed by Finnish architect Viljo Revell, and sits before Nathan Phillips Square. Nathan Phillips Square is home to the pond/ice rink as well as the 3D Toronto sign installed in 2015 for the PanAm Games, both which are major landmarks of the city.

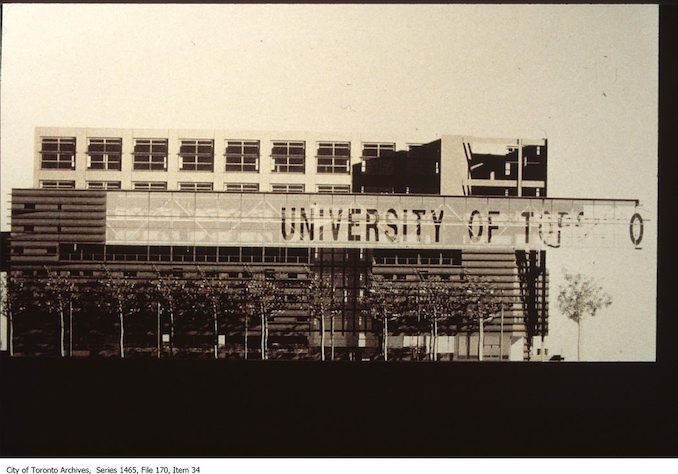

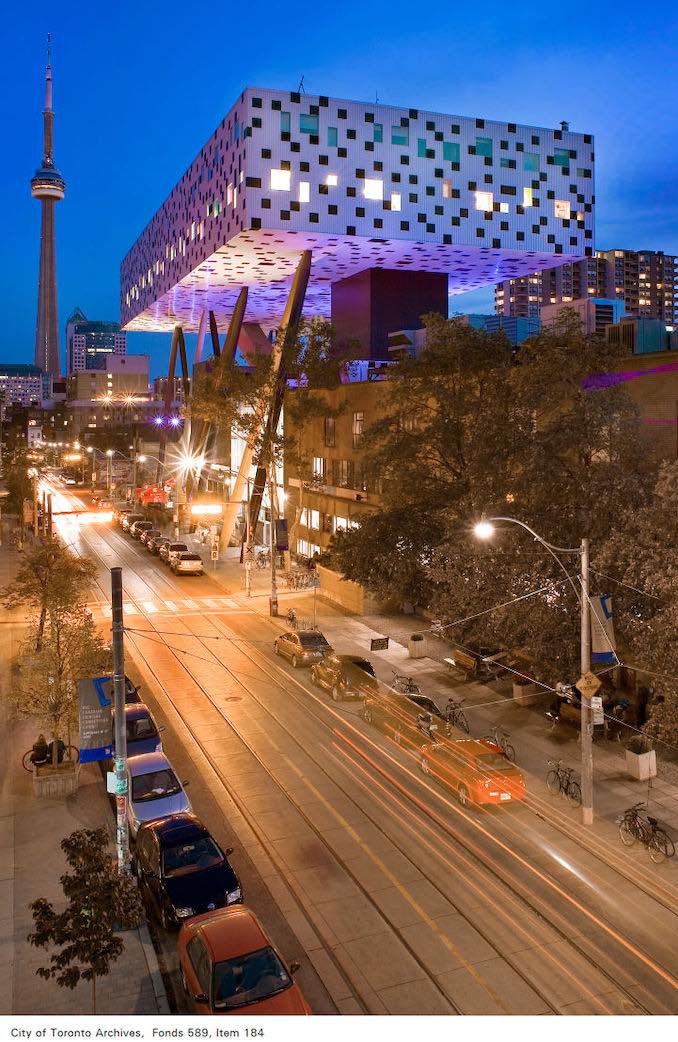

Toronto’s abundant University culture also plays an important role in its architectural diversity. The University of Toronto (U of T) embodies monumentalism, and sprawls across the centre of the city, thus having a wide impact on its architectural atmosphere. Having been built up over almost two centuries, the university’s buildings cover a wide range of styles and trends from different time periods. The Collegiate Gothic style was utilized in many of the original buildings, such as Hart House, Trinity College, and Burwash Hall. In recent decades, the structures have taken inspiration from the styles of modernism, brutalism and postmodernism in the McLennan Physical Laboratories, Robarts Library, and the graduate house, respectively. Conversely, The Ontario College of Art and Design, consists of a collection of dramatic structures, having been remodeled in 2004 by the addition of the Will Alsop’s Sharp Centre of Design. Its contemporary design adds a splash of modernism to the Victorian style houses and small shops surrounding it. The lofty building consists of a large black and white speckled box suspended four storeys off the ground and supported by a group of brightly coloured pillars at differing angles.