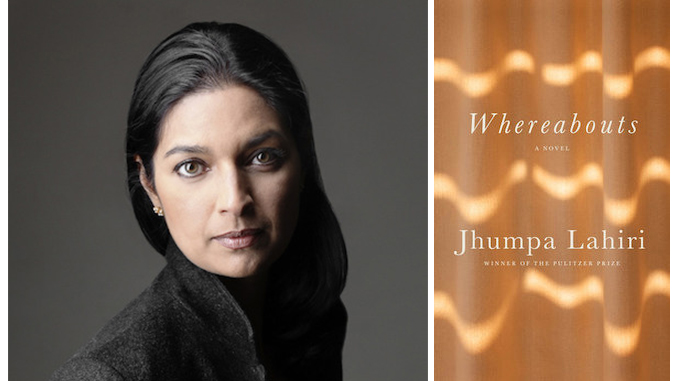

Jhumpa Lahiri’s Whereabouts, her first novel in eight years, is an interesting experiment, though an experiment nonetheless. Between its micro-chapters, unnamed protagonist in an unnamed city, and preference for observation and anecdote over story, it often seems more like an exercise in form than a fully-formed work.

To be fair, that experiment mostly succeeds. The vignettes are interesting, or failing that, well-observed. The chapters are also so short that it is impossible to get bored – you’re only ever a page or two away from the next scene.

At fifty or so distinct, and largely unrelated, episodes, Whereabouts has the inescapable feel of peeking between the pages of someone’s diary. Albeit, one left carelessly open in a prominent place, inviting the curious reader.

LIFE, ITALIAN STYLE

Jhumpa Lahiri first came to prominence with Interpreter of Maladies (1999), a rather lovely collection of short stories set primarily in the Indian diaspora. Interpreter won Lahiri a Pulitzer, an impressive feat for a debut, and in the years since she has maintained a remarkably consistent track record, from the megahit (and subsequent film) The Namesake (2003) through the Booker-nominated The Lowland (2013).

In 2013, Lahiri – a British-American of Indian descent – dropped off the English literary landscape. This was a conscious if unusual choice: relocating to Rome, she devoted several years to learning Italian, only to begin exclusively writing in her newly acquired language. She has since published two Italian-language collections of non-fiction essays, as well as Dove mi trovo (2018), now appearing in English translation as Whereabouts.

Whereabouts is an unusual specimen, almost a convergence of Lahiri’s many literary and personal lives. Written in the first-person present, it could easily be mistaken for one of her personal essays, if not for the revelation that its unnamed narrator is a native-born Italian. At the same time, it reads like a short story collection, with exceedingly short chapters that max out at about four pages, each one a discrete vignette in the life of its central character.

However, Lahiri – or perhaps her publisher – has seen fit to describe Whereabouts as a novel. That label fits, but only barely. There is no narrative throughline, and the only real commonality between chapters is the narrator’s presence. Characters rarely appear more than once, and, with one or two minor exceptions, the vignettes could basically be read in any order. Aside from a handful of dialogue sequences, the entirety of the novel consists of the private musings of one lonely woman and the relatively small world that she inhabits.

ITALIAN IMPRESSIONISM

Whereabouts is, above all, a study in loneliness, of one woman’s inability to make or maintain connections. The narrator moves through life quietly, introspectively, and largely without companionship. Though we are privy to much of her inner life, she doles out only the barest of biographical details: she is single, middle-aged, has a difficult relationship with her parents (one deceased, one fading), and is without much apparent romantic success. She seems accustomed to her loneliness, though a certain wistfulness does, on occasion, suggest that she longs for more.

Nominally, each episode in Whereabouts is situated in a particular time or place, signified by chapter title: “At the Ticket Counter”, “On the Balcony”, “In the Bookstore”, etc. Much of the time, we are witness to some minor incident – a run-in with an acquaintance, a visit with the narrator’s mother – which acts as a kind of narrative snapshot, or incomplete portrait. Lahiri is good at giving us the flavour of a moment, though she rarely colours in the details. Which, really, is too bad, as certain chapters beg of a longer interaction – a visit from an old friend and her obnoxious husband springs to mind.

That said, a chapter is just as likely to pursue a theme – the impression left by a deceased predecessor “In the Office”, for example, or the beautiful yet frigid life of a city “In Winter”. Such sequences might be considered landscapes, accompanying the portraits described above. And while these prose impressions are not always beautiful or even particularly interesting, they are always enjoyable: minute, precise exercises in description and mood.

In an early chapter, for example, the narrator checks in on a friend’s teenage daughter, now living alone, and finds that the girl is all grown up and quite comfortable on her own. The narrator sees the visit as an obligation, only to discover that she is no longer needed.

Later, she describes swimming in the local pool that she frequents, a place where she sees the same familiar faces each visit: “eight different lives share that water at a time, never intersecting.” The observation works on two levels, both as literal statement and as metaphor.

SOLITARIA

Whereabouts represents the first time Lahiri has translated one of her Italian works into English, an approach that, inevitably, draws comparisons with Samuel Beckett. The Irish novelist and playwright famously wrote many of his works in French first, before translating into his native English. For Beckett, the effort of writing in a second language forced him to think clearly and avoid the temptations of rhetorical flourish:

It is indeed getting more and more difficult, even pointless, for me to write in formal English. And more and more my language appears to me like a veil which one has to tear apart in order to get to those things (or the nothingness) lying behind it.

Unsurprisingly, Lahiri has long evinced a similar philosophy. There has always been a grace, a lack of pretension, to her prose; what she has called her love of the “plain”. Consider this interview from over a decade ago (and three years before her move to Rome), in which she tells the interviewer, “Even now in my own work, I just want to get it less—get it plainer.”

Whereabouts certainly accomplishes that goal, its sparse prose conveying the fleeting thoughts of a narrator who is both lonely and yet very much of the world. She lives in a particular place and in a particular community, but she always stands slightly apart. She has friends and family to call upon and to be called upon by – but only when she allows it.

It is perhaps this attitude towards the world which helps to explain the structure of Whereabouts itself. Wandering the empty streets of an unnamed Italian city, speaking quietly to herself, the narrator catches at bits and pieces of her world, never lingering for long.

***

Visit the official page for Whereabouts here.