For the last 100 years, the now dubbed Ed Mirvish Theatre has weathered its fair share of plot twists both on and off stage. Currently known for hosting a variety of lauded Broadway shows such as Wicked, Hamilton, and Come From Away, the charming vintage building has become the hub of musical and theatrical productions for all of Toronto. The story of this transportive property takes place within 3 phases, morphing from one entertainment form to the next maintaining class and grace on the surface, while undergoing a dark slew of scandal behind the scenes.

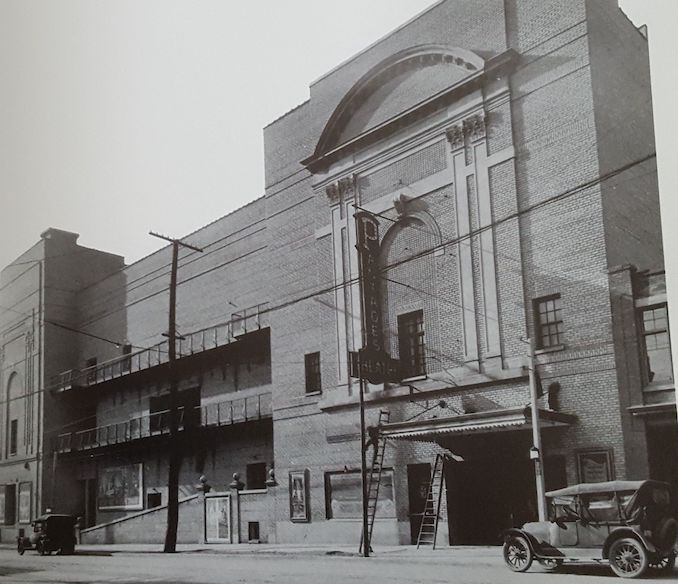

The vaudeville days were among its most quaint. In 1919, during an economic boom succeeding the first world war, the half a million citizens of Toronto were gleeful with pride and liberated in their newfound monetary freedom. A notorious weight had been lifted off the city’s shoulders and the airs of creativity and boisterousness were free to flow once again.

While the core of downtown was somewhat rich in the performing arts containing a colourful variety of theatres presenting drama, comedy and musicals, one particular form of entertainment’s absence had left a void. Vaudeville was a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. In North America, it had been gaining traction since the 1850s, and was recognized and enjoyed as light entertainment that consisted of about 10 individual unrelated acts, featuring magicians, acrobats, comedians, trained animals, jugglers, singers, and dancers. The community was akin to a circus, home to a group of prominent vaudeville performers who would travel all throughout the continents in cliques, bringing with them sparks of laughter and joy at every venue they made an appearance at.

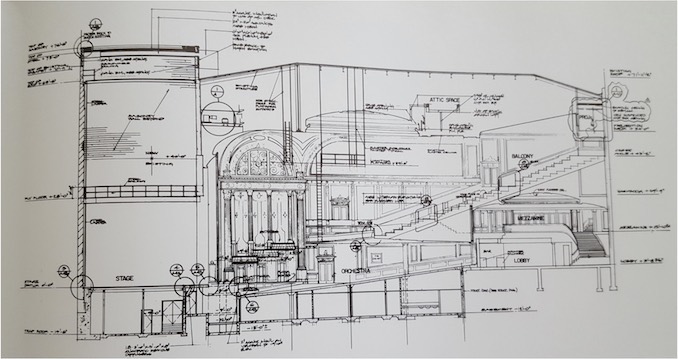

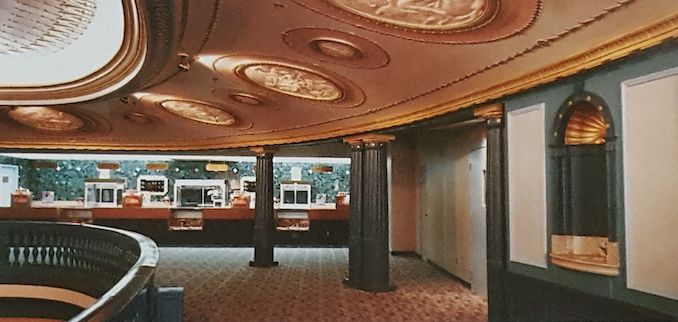

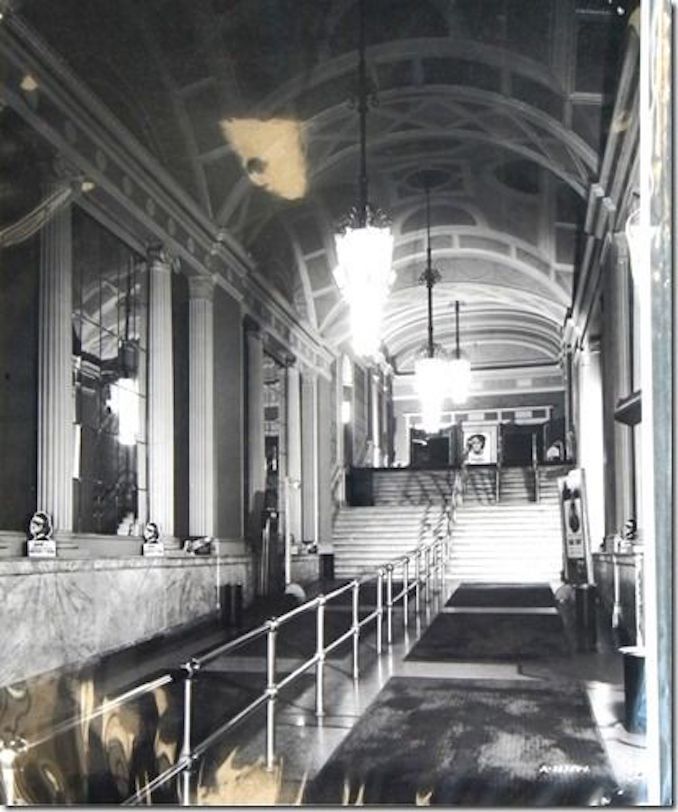

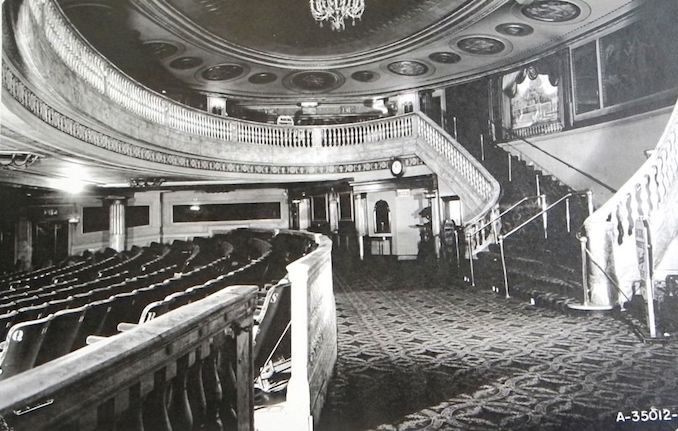

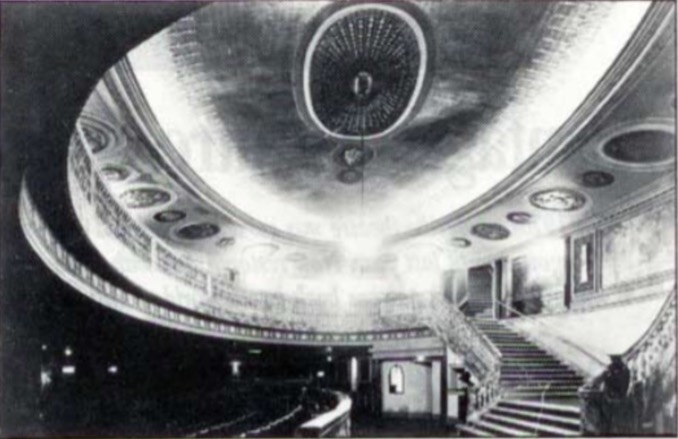

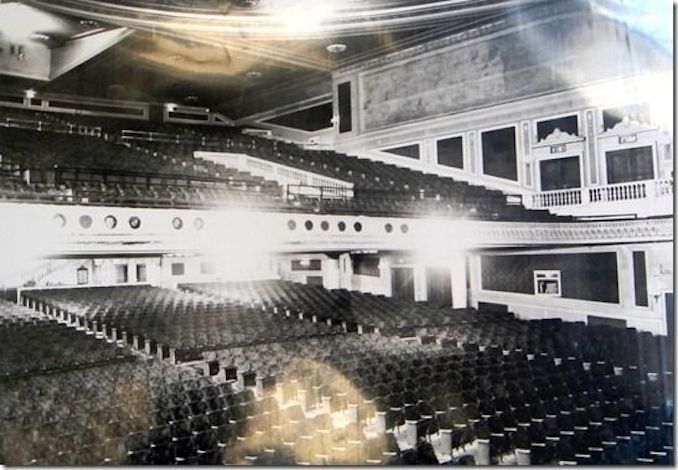

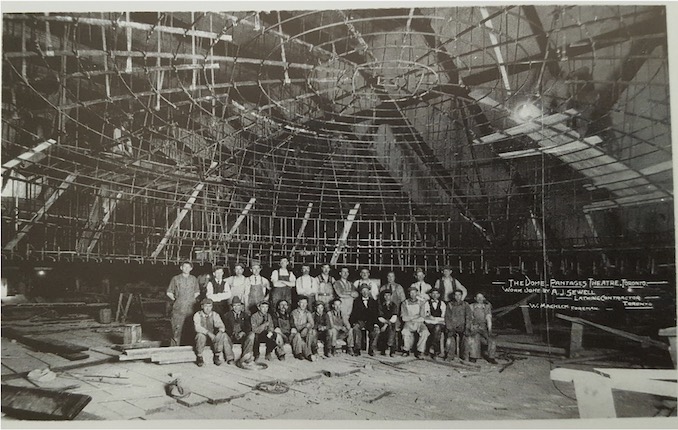

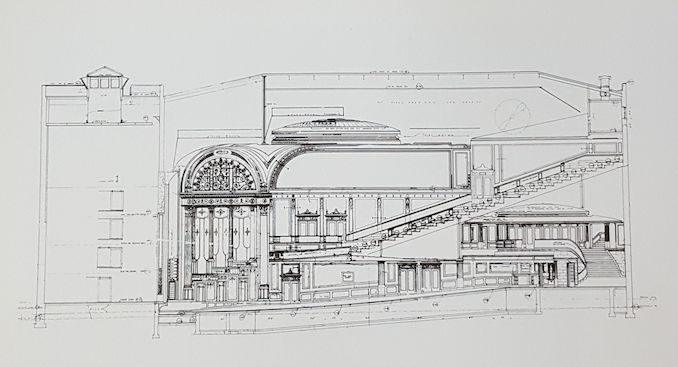

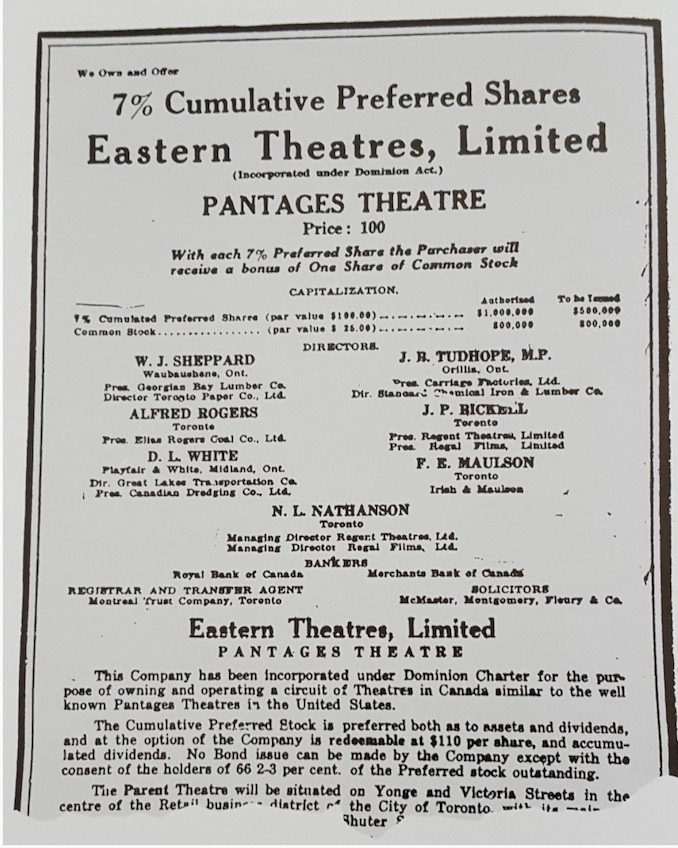

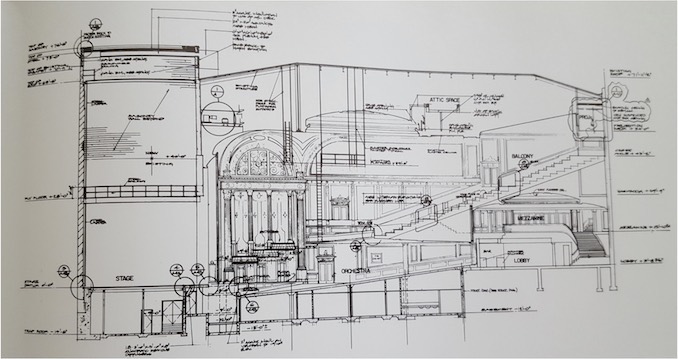

Nathan Nathason was the original visionary of the theatre, aspiring that one day the most celebrated performers in the world would cycle through his modest Toronto location. To execute his intent, he hired the most prominent architect of the time, Thomas Lamb. Working tirelessly to fabricate the extravagant and elegant theatre that we know today, Lamb worked with the 2 building styles Adam and Empire. He combined the flamboyant finishes of these two styles with neo-classical symmetry. Walls and ceilings were adorned with mouldings of oval fans, garlands and several other traditional ornaments such as panels, niches and stretching Greek columns.

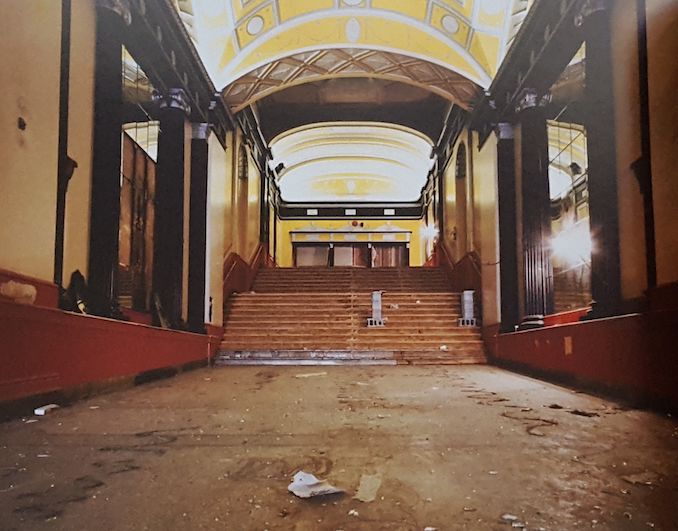

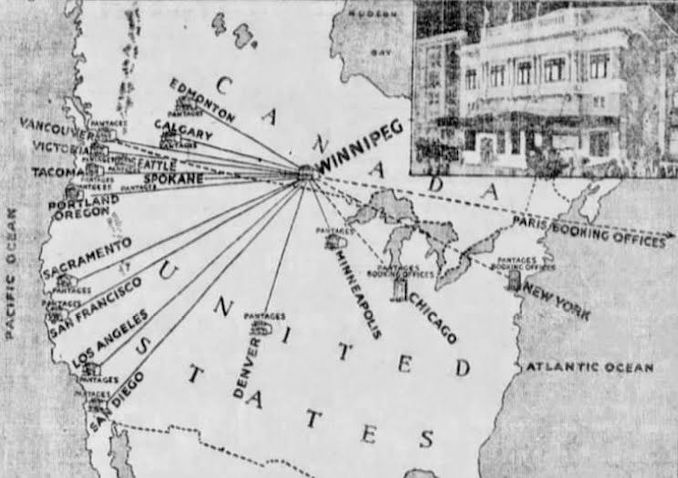

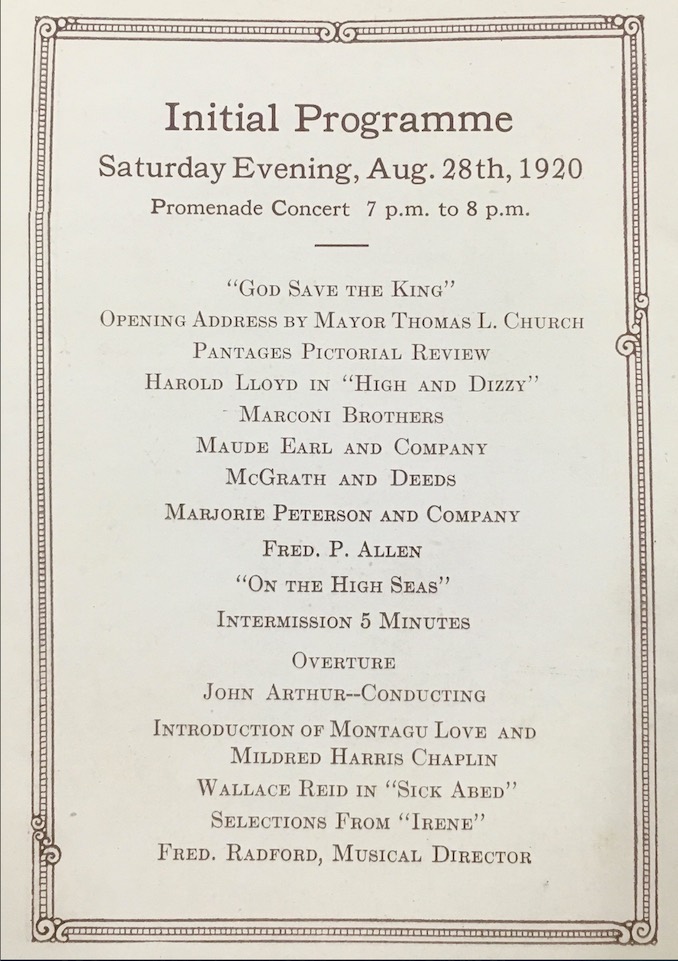

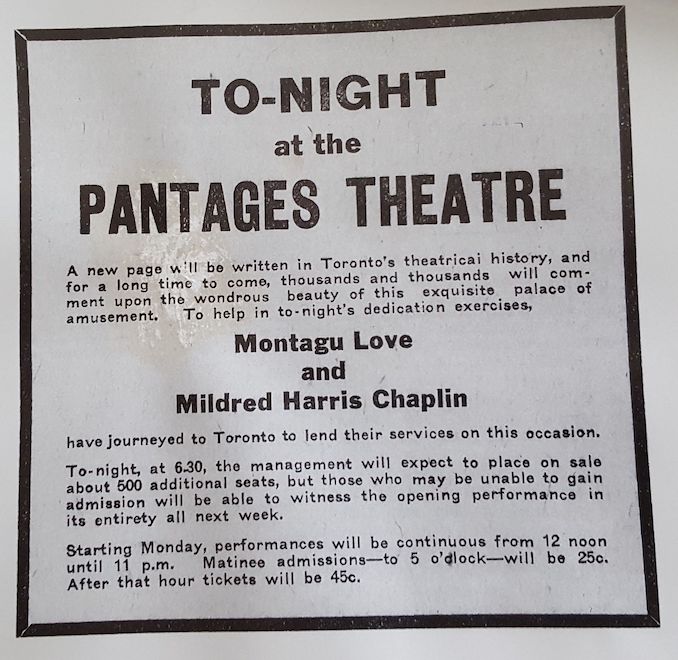

To ensure that entertainment in his deceptively sprawling theatre would never run dry, Nathanson collaborated with Paramount Pictures to form Famous Players Canada. Soon this company signed onto the Pantages vaudeville circuit, an established network of over 70 theatres on the continent. After months of laborious works, on August 28, 1920, an ad in The Evening Telegram announced that “TO-NIGHT AT THE PANTAGES THEATRE – A new page will be written in Toronto’s theatrical history”. That night for the first time Pantages theatre opened its grand oak doors which led to an escape of sophistication and culture. Throughout the 1920s, the Pantages theatre held true to its promise of providing unparalleled vaudeville acts uninterruptedly from 12 pm to 11 pm with admission an affordable 25 cents for matinees, and 45 cents after 5 pm.

As the decade neared its end, vaudeville was subtly growing obsolete as motion picture features began being thrust to the forefront. The once popular miscellaneous style of frivolous acts that were the crown jewel of the performing arts world, and was now fading to the background, making room for a more revolutionized method of entertainment.

The phrase “talkies” was often tossed in conversation, referring to the talking pictures which were rising in popularity. However, while the shift in popularity was a driving factor, the real reason for the Pantages Theatre’s hasty turnaround was in fact the result of a vicious smear campaign. Alexander Pantages, the CEO of company, was under suspicion and convicted of attempted rape. During the course of a retrial, it was found that RKO Pictures had deceptively “staged” the attempted rape in order to diminish the reputation of the Pantages empire and broker a selling deal for far below its value. While the Toronto Pantages Theatre was not officially owned by Pantages and therefore was not subject to this deal, it was urged to change its name to rid itself of the name’s negative connotations.

On March 15, 1930, the theatre was officially renamed the Imperial Theatre, and soon evolved into a landmark for long anticipated movies obsessed over by the public. By 1935, it became exclusively a cinema, and thus underwent some monumental changes which symbolized its modernization and an elusive attempt at diminishing its history in the interest of corporatization. Some of these changes included the filling of the orchestra pit with concrete and the emptying of the box seats. After many lively decades of serving as a single screen movie house, equipped only to show one movie at a time, the cinema began to decline in profit as television’s reign had sprung from its infancy.

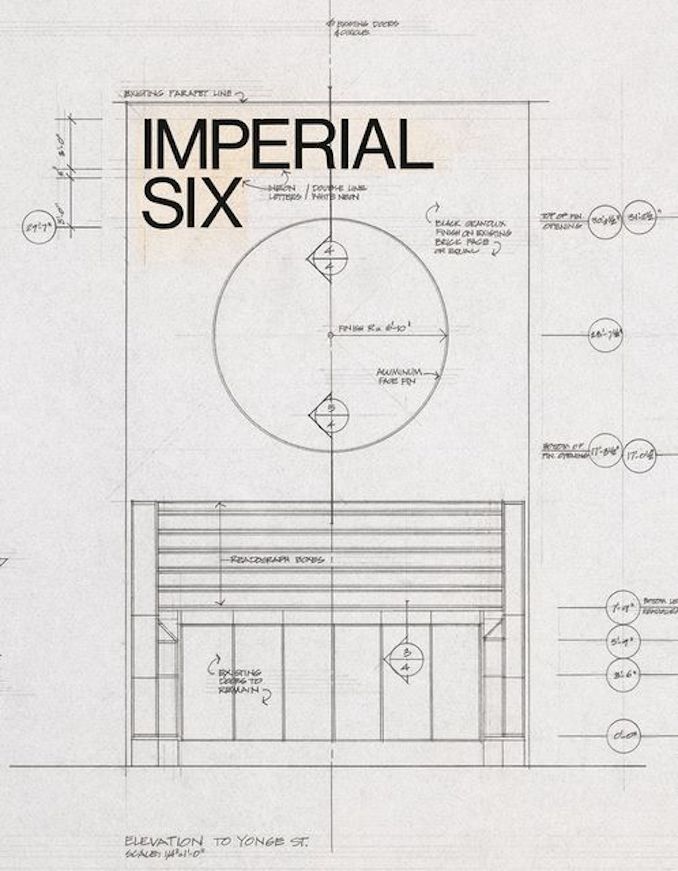

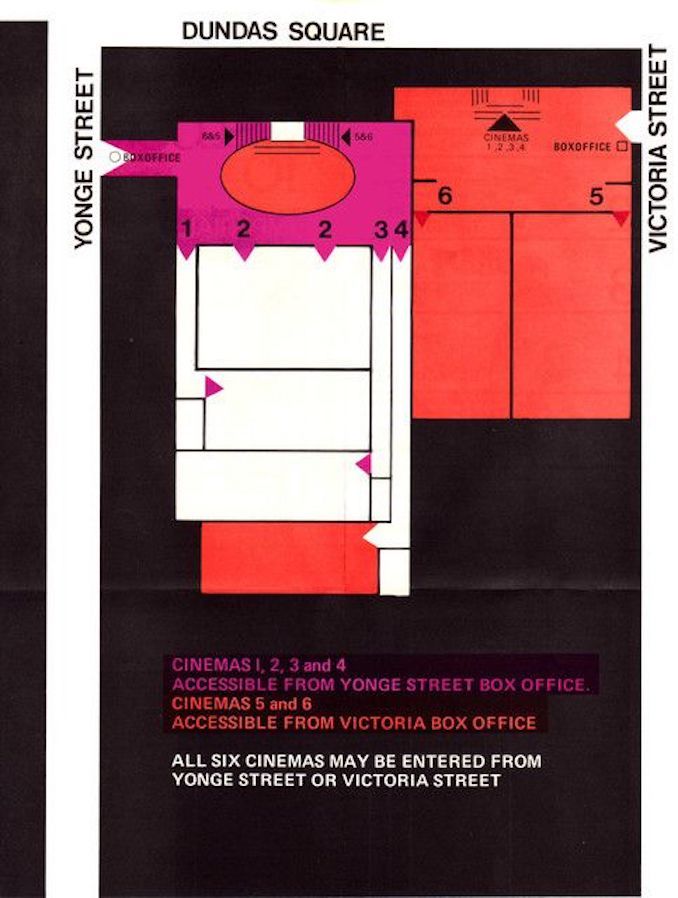

Thus on September 4, 1972, the cinema had its last showing of the unprecedentedly popular The Godfather. To resurrect this problem, the once old fashioned and twee entertainment house was startlingly reconfigured by architect Mandel Sprachman, and split into 6 separate smaller chambers. To further accomplish the goal of rebranding the cinema to fall back in line with the likings of the current day, many characteristic architectural features were demolished or replaced including the proscenium arch, portions of the balcony, the grand ceiling dome, the stained-glass window, and the original marquee. With this once again new beginning, entertainment at the Imperial Six recommenced, becoming one of the world’s first multiplexes. For a brief moment, the city was overcome with a sense of levity.

Unfortunately, the theatre was quickly plagued with yet another heart wrenching scandal, one that would close its doors for over an entire year. A dispute struck out over confusion of the renewed lease of a portion of the property, and resulted in a bitter circuit of courtroom drama between Famous Players and Cineplex Odeon. This eventually led to the resentful selling of the entire plot of land to Cineplex in 1988 on the condition that the property would never be used to present motion pictures again.

After a bouquet of dramatic events in the theatre’s past, Cineplex felt it only right to pay homage to the original venue that had once upon a time cropped up on Toronto’s crowded Yonge Street. In their new design of the theatre, tremendous efforts were made to reincorporate the authentic features of the building in order to restore its initial opulence and splendour. The propellers of this project were so keen on this attempt, that one even went so far as to seek out the signature stained-glass window (which had been lost for decades) in the window of a Rosedale private residence. On September 20, 1989, the newly refurbished theatre house opened with The Phantom of the Opera.

With a vintage flair the theatre rebirthed the luxurious and exciting vibe of a sparkling night out at the theatre from the 1920s, as fans flocked in fawning over the musical and the niche features that truly refreshed the building from it’s history of dark tales. The show became a roaring success and attracted fans for a record breaking 10 years. Finally, in 2008, the dedicated and enthusiastic manager David Mirvish purchased the theatre, and

named it after his late father. Alas, a new name was dawned upon the venue as it has since been called the Ed Mirvish Theatre.

Throughout it’s time on our crammed streets of Toronto, this theatre has cycled through the decades as time has tested it, enduring both the hardships that scandal and competition has brought it, along with the joy and eccentricity of the ever changing and evolving performing arts.