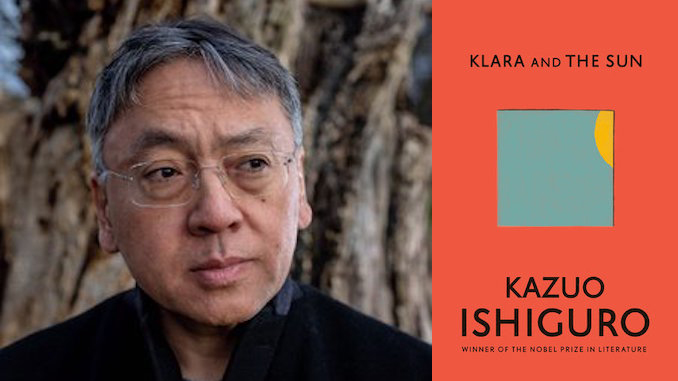

Kazuo Ishiguro’s much-anticipated Klara and the Sun, his first novel since winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2017, is likely his most earnest work, and also his most straightforward. Perhaps because of this, it is also a lesser work; a well-meaning but hardly revelatory rumination on love, faith, and faith in the power of love. And if that sounds trite, well, then you already understand Klara‘s flaws.

That said, I enjoyed Klara, and it serves as a nice antidote to the cynicism that plagues a lot of contemporary fiction. But Chicken Soup for the Robot Soul was not quite what I was expecting.

ME AND KLARA AND THE DYING GIRL

Like nearly all of Ishiguro’s novels, Klara is written in the retrospective first-person, the narrator recalling a period in which they played a small but important part in someone else’s life. In Remains of the Day, easily Ishiguro’s masterpiece, that narrator was the long-serving butler Mr. Stevens. Here, it is a character in a similarly servile role: Klara, a highly sophisticated robot – referred to in-universe as an Artificial Friend, or “AF” – who has been brought into the home of a severely ill teenage girl named Josie. Klara, we soon learn, is unusually intelligent and perceptive for an AF – an observation that is repeatedly, and somewhat annoyingly, hammered home by many different characters over the course of the novel.

Part One of Klara quickly sets the tone for the rest of the novel: set in a kind of robotic pet store, we follow Klara as she anxiously hopes to be purchased and taken to a good home. When Josie enters Klara’s life – a lively girl suffering from a serious but largely undefined illness – it gives Josie the perfect opportunity to be the ideal AF – attentive, loyal, and eager to please.

This includes acting unquestioningly on Josie’s and her mother’s wishes; doing her best not to clash with the eternally bitter (and thinly characterized) housekeeper Melania, a woman of vaguely Eastern-European origins and, god help us, a possible reference to the former First Lady; and, perhaps most importantly, acting as a go-between for Josie and her neighbour/best friend Rick. It’s easy to read Klara as a kind of “Fifth Business” for a number of human characters, including Josie and her divorced parents; the neighbour Rick, his mother, and the man who might help Rick get into college; and the artist hired by Josie’s mother to preserve Josie’s memory, in the event that the girl dies.

I, ROBOT

As a narrative device, having the novel told from the perspective of a sophisticated Artificial Intelligence is a good one. Ishiguro has worked out his own scheme for what might make the self-narrative of an AI/AF/robot different, landing on a kind of studied naïvité that suggests we would be wrong to take Klara entirely at face value. For example, following an incident in which Klara is taken on a “family outing” while Josie is left at home, we probably should not trust Klara’s protestations that she cannot understand why Josie is upset with her. Still, Klara’s overall difficulty in understanding the fraught dynamic between Josie and her mother is probably truthful, given Klara’s recent entry into the family, and general lack of human experience. Ishiguro does a fine job of threading the line between where an AI might actually falter, and where an AI, cautious about revealing its abilities, might only pretend.

Similarly, Klara’s steadfast insistence on waiting for instruction – she will, for example, refuse to enter a room unless explicitly told to do so – is belied by her great wonder for the outside world, and eagerness to venture out on her own. Klara seems to operate by her own set of rules, ones that are meant to be bent, if not entirely broken. This is especially so as Klara becomes more intent on her mission of self-sacrificing love, finding more and more excuses to act of her own free will, all while implausibly claiming she only acts on human orders.

There’s also something quite sympathetic about Klara’s limited physical capabilities. She gets lost easily, struggles to navigate even the simplest landscapes, and the slightest shift in terrain can cause her to stumble. It’s never explicitly stated, but it’s hard not to read these physical limitations as a kind of built-in precaution against a Skynet-style robot revolution. (Maybe Boston Dynamics should take a cue.)

THE GRID

While Ishiguro admirably avoids the temptation to go too hard on the sci-fi, his best touches are the perceptive quirks that form part of Klara’s experience. This includes the way that Klara will see, in a single moment, a cross-section of the present and past. Such moments are not, for Klara, dreams or hallucinations, but more akin to the way a human might remember one thing while looking at something else. Here, for example, Klara describes a visit to an abandoned barn, in which she “sees” objects pulled from different moments in her life. We are clearly not meant to take the presence of these objects (a shelf in her old store, a blender from the family kitchen, etc.) as literal:

Beyond the hay blocks was the real wall of the barn, and I was pleased to see the Red Shelves from our old store still attached to it, though this evening they’d become crooked, slanting noticeable towards the rear of the building. The ceramic coffee cups had maintained their orderly line, but there were also signs of confusion: for instance, further on the same tier, I could see an object that was unmistakably Melania Housekeeper’s food blender.

Klara also has a fascinating tendency to divide the world up into what she calls “boxes”. This, we are led to understand, is an actual visual phenomenon, in which the world is neatly compartmentalized, though elements within it may take on strange aspects. It resembles, more than anything else, a Cubist painting:

Their heads were almost touching, and because of how they were standing, the upper parts of their faces, including all their eyes, had been placed in a box on the higher tier, while all their mouths and chins had been squeezed into a lower box… Over at the rear wall, three boys were seated on the modular sofa, and even though they were sitting apart, their heads had been placed together inside a single box, while the outstretched leg of the boy nearest the window extended not only across the neighbouring box, but right into the one beyond.

While Klara initially has some control over this phenomenon, the visual breakdowns increasingly happen at inopportune moments, even as the imagery becomes more and more abstract. Overwhelmed by a crowd, for example, Klara describes the people around her as “constructed out of cones and cylinders, made from smooth card.”

What is especially fascinating is that these moments are written as literally and even-handedly as the rest of the novel. Klara offers no explanation for what she is seeing since, for her, these shifts in perspective are simply part of her experience of the world. She assumes the reader is as intimate with this visual vocabulary as she is.

UNBEARABLY NAIVE

Reading Klara, it is impossible to not be reminded of other works of speculative fiction, including Ishiguro’s own. In particular, the slowly revealed nature of the teen girl’s illness, and the lengths her mother is prepared to go to save her, contain strong parallels to Ishiguro’s 2005 Booker-nominated Never Let Me Go.

Inevitably, Klara also reminds us of the countless works of fiction iterating on Isaac Asimov’s seminal writings on artificial intelligence. Of all those references, one immediately leapt out at me while reading Klara. It comes from, of all things, the least-loved Avengers movie, 2015’s Age of Ultron. That film saw the debut of the character Vision, a robot who is built in a day, swears immediate allegiance to his human creators, and proceeds to save the world the day after. At the climax of the film, the titular supervillain accuses Vision of being “unbearably naïve.” To which Vision replies, “well, I was born yesterday.”

It’s a great line, and applies just as well to Vision as it does to the title character of Klara and the Sun. Ishiguro’s creation is, at best, a few weeks old at the time Josie takes her home, simultaneously perceptive to a degree unheard of for AFs, yet lacking in human experience. Her commitment to humanity is admirable, but it is also rather naïve – something that Klara is herself aware of, and exploits every time she (dubiously) pleads ignorance.

Unbearably naïve as she may be, Klara’s selfless love for Josie is undoubtedly authentic, as evidenced by the great lengths she goes to in trying to save the girl’s life (and which help explain the novel’s title). Not bad for a robot girl born yesterday.

***

Visit the official page for Klara and the Sun here.