I must have been about 3 years old when my older brother first let me read one of his comic books. I don’t remember the issue, or what it was about, or even the experience of reading it. The only thing I’m certain of is that it was a Marvel comic.

For ours was a Marvel household, and if my brother was going to introduce me to the beautiful wide world of four-colour adventures, he was damned sure that my first taste was going to be the very best of the genre.

And Marvel was the best. Still is, for my money. For in Spider-Man, and the X-Men, and the Avengers, and Daredevil, and the Hulk, and – well, just turn to Wikipedia’s list of Stan Lee creations – Lee, and his many brilliant co-creators, effectively invented the modern superhero. And he did so with one simple insight: Stan Lee’s characters were human.

Which is to say: Marvel superheroes were the first to have flaws. The first to be “feared and hated by a world they have sworn to protect” (the X-Men). The first to be the ones who didn’t get the girl. Who weren’t, as Stan Lee put it in Amazing Spider-Man #5, “BMOC”, Big Man On Campus. Unlike their predecessors, those characters from the 1930s and 1940s like Batman and Superman and Captain America, Stan Lee’s heroes were not, or at least not entirely, square-jawed muscular white males with names like “Steve” and “Bruce”.

The Marvel era represented a profound shift in the way superhero stories were told, in what writers and artists expected of their readers, and in what they expected of their comics. In many ways, comic books got smart, or at least wise enough to know that readers wanted more than pure fantasy. Lee, and his all-too-often overlooked co-creators, gave us the tortured Jekyll/Hide soul of Bruce Banner/the Incredible Hulk, the eternally put-upon scrawny teenager Peter Parker/Spider-Man, and – especially – the civil rights analog X-Men, hated for being different, though if you pricked them, they bled just like the rest of us.

They were, in a word, relatable. Humans, albeit ones with supernatural abilities, who struggled to make ends meet, whose alter egos were bullied at school, who could let their greed get in the way of their responsibilities. This cannot be overemphasized: in those early days of Marvel, no comic had ever devoted that much thought, let alone actual page count, to the mundanities and challenges of everyday life. Sure, superheroes were and remained a power fantasy, but what Lee recognised – and this truly is his greatest contribution to the genre – is that the best fantasy is one that, in some shape or form, reflects the reality of the reader. Batman is cool, yes, with his mansion and his fancy car and his butler. But Spider-Man is me. Or at least, Peter Parker is the version of me that, for a certain period of my adolescence, I longed to be.

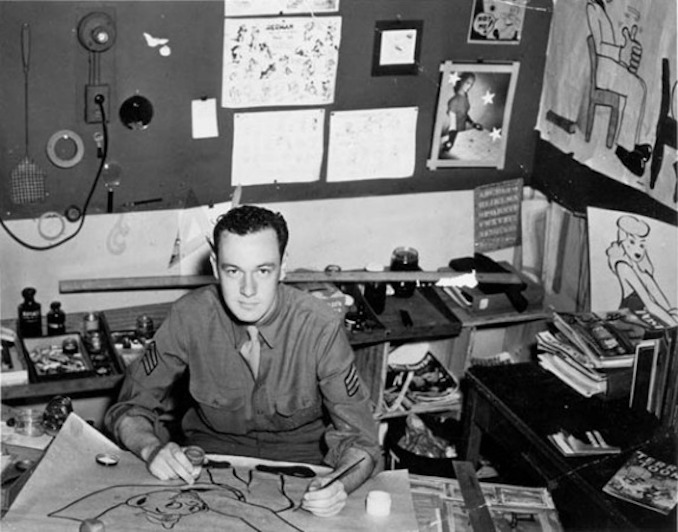

Stan Lee was also me, a Jewish boy of Eastern European heritage, and it’s not lost on me that a lot of his work, especially the early stuff, looks like the kind of thing a Jewish kid growing up in the 1930s might idealize about the white Christian society that he’d been born into. But as the fans know, Lee traded in far more than just adolescent male power fantasies. Once he set about making his heroes human, it wasn’t long before his realization that – Hollywood take note – the world did not begin and end with the all-American teenage boy.

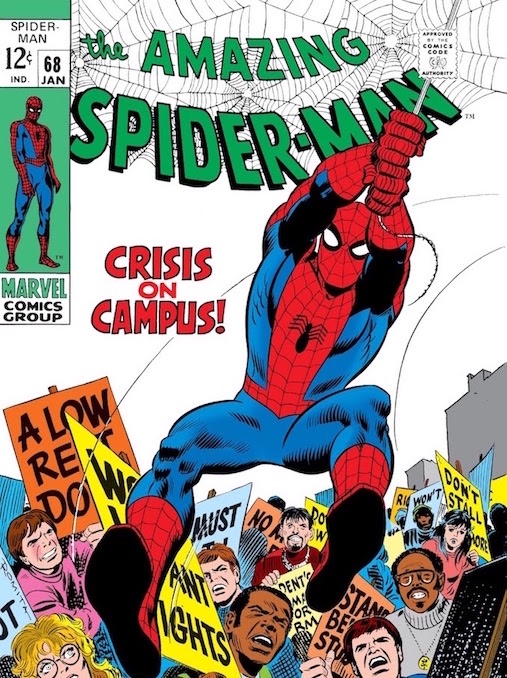

Take Amazing Spider-Man #68 (cover date: January, 1969). In this issue, the dastardly Kingpin’s plot to steal an ancient artifact shares roughly equal space with a storyline about student protests, one largely centred on Randy Robertson, an African-American student. While the protests are nominally about low-income student housing, the cover, depicting a multicultural group of youth holding signs like “We Want Rights”, couldn’t be clearer about the underlying tensions.

Of course, Lee’s engagement with the civil rights movement was more consequential than a B-plot here and there. Much has been written about the X-Men and Lee’s intentions for the characters, with the peaceful Professor X and the more aggressive Magneto serving as (occasionally inelegant) proxies for the debates within the movement. I could cite dozens if not hundreds of other Lee stories that were even more explicitly rights-focused, though I have a soft spot for the Spider-issue above, in part because it captures that one corner of the movement so well.

And then there’s Black Panther. King T’Challa, as he is also known, debuted in July 1966, within days of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Soldier Field rally alongside Stevie Wonder, Peter, Paul, and Mary, and about 35,000 others. It’s no coincidence that just at the moment King was preaching the gospel of civil rights and fair housing, readers of Fantastic Four # 52 were being treated to the debut of the world’s first major Black superhero. But – and this is once more to Lee’s credit – right from the very beginning, T’Challa was so much more than just a Black hero. Where worse or lazier writers might have focused uniquely on Panther’s blackness, Lee did one better: he presented T’Challa as just another hero. One instantly accepted by the existing (white) heroes, who recognized his intelligence and ability, and who never questioned his right to stand alongside them. When he was invited to be an Avenger – by Captain America, no less – it was because he was, quite simply, a great candidate to be an Avenger.

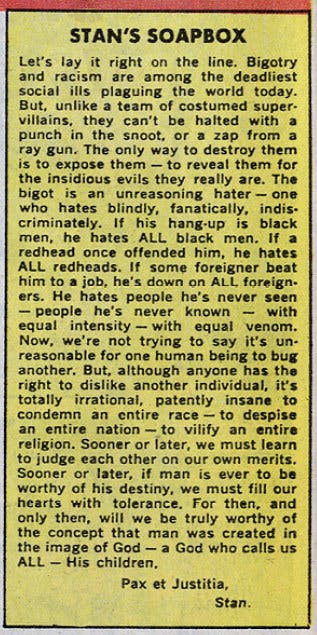

Not that Black Panther, and Lee’s Marvel, didn’t also confront racism and sexism (and as the decades went on, homophobia and other social ills) head-on. Indeed, Marvel was famous for it. In a celebrated December 1968 “Stan’s Soapbox”, Lee laid down the Marvel ethos, partly as a response to some readers complaining about “Marvel moralizing”. It’s worth reprinting in full, and you may well have already seen it making the rounds on social media:

You can see the influence of this in the fact that, today, Marvel far and away outdoes the Distinguished Competition in their willingness to engage with concerns about equality and representation. You can see it, for example, in Marvel’s recent overhaul of the “core” roster, handing the mantles of some major superheroes – Thor, Wolverine, Spider-Man, Captain America, others – to female characters and to persons of colour. One of Marvel’s shining stars right now is a Muslim teenage superhero named Ms Marvel, aka Kamala Khan. This is Lee’s legacy.

But Stan Lee wasn’t perfect. He downplayed the contributions of co-creators, and he was notorious for financially and creatively short-changing writers, artists, editors, and other Marvel staffers. Many fans will never forgive him for driving Jack Kirby – co-creator of the Avengers and about a billion other noteworthy characters – out of the Marvel family, not to mention Kirby’s fair share of Marvel royalties. That Lee was so successful and worked so long was probably a result, as he half-joked in an interview at the age of 92, of being driven “by greed. Pure greed.”

Stan Lee was flawed. Imperfect. On the one hand, there was Stan the Man, the great creator, the one who gave the world such amazing – uncanny! incredible! – characters. But there was also Stan Lee, the man, a selfish businessman who could treat friends and colleagues badly, and who, in the words of legendary comics writer Gerry Conway, “is a good guy. He’s just not a great guy.”

In other words, like Peter Parker, and Tony Stark, and Bruce Banner, and Matt Murdock, and [insert your favourite Marvel hero here], Stan Lee was just like the rest of us.

Human.