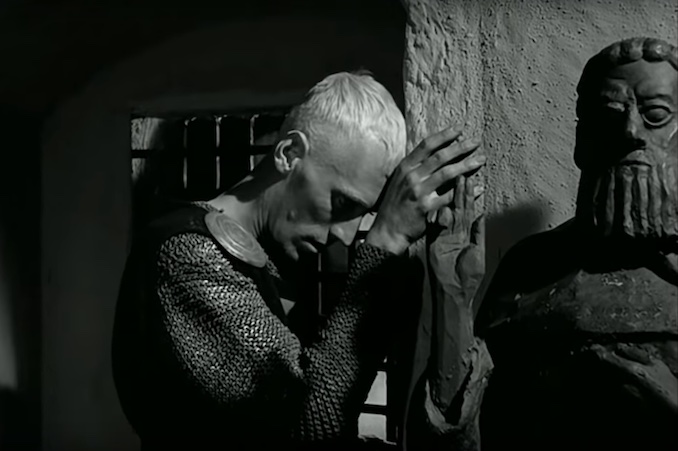

A Medieval knight stands by the grille of a church confessional. He presses a hand to the stone wall, steadying himself. He speaks:

“I want to confess as honestly as I can, but my heart is empty. The emptiness is a mirror turned towards my own face. I see myself in it and am seized by disgust and fear.” The knight pauses, smiles enigmatically, then continues: “Through my indifference for people, I’ve been placed outside of their society. I now live in a ghost world, enclosed in my dreams and fantasies.”

The words are Ingmar Bergman’s. The voice, and the subtle, expressive face that bring them to life, belong to arguably Bergman’s greatest collaborator, Max von Sydow.

When Max von Sydow died earlier this week at the age of 90, the world lost one of its great actors. Perhaps the great actor of the non-English-speaking world, though von Sydow also had his fair share of English-speaking (and French-speaking) roles.

Max von Sydow was certainly one of the most consistently brilliant of actors. From his breakout role in The Seventh Seal (1957) (in which the above confessional scene appears and in which he famously plays chess with Death), through his eleven-film collaboration with director Ingmar Bergman, and on through his quasi-comedic turn in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and appearances in sci-fi/fantasy nonsense like The Exorcist and Game of Thrones, von Sydow was never anything less than compelling to watch.

His chiseled face, those piercing blue eyes, that tall and lanky body; these qualities, combined with a keen intelligence and the insights of a born actor, made for someone who could, if he so desired, dominate every scene he was in. That he did not is a testament to von Sydow’s skill as an actor, a man who could recede into his characters, often tortured, sometimes pathetic, but always fascinating. He could, with a tensed muscle, a burying of his head in his hands, or – in one of the great Bergman scenes – while wrestling a birch tree, express all the conflict and confusion of being.

Despite his reputation for cold, cruel (and later, villainous) roles, von Sydow could also be immensely sympathetic. As the grieving father who, after enacting a terrible vengeance in The Virgin Spring (1960), swears penance to God in the film’s closing moments, he is almost unbearably pitiable: a broken man who, despite what has happened and what he has done, seeks out hope in faith.

A few years later, as the suicidal parishioner suffering from a debilitating fear of nuclear annihilation in Winter Light (1963), he again shows how physical strength – at 6’4″ and with those gaunt Swedish features, Max von Sydow could be an imposing figure – is powerless against the fragility of the human psyche. Winter Light makes for a fascinating pendant to Through a Glass Darkly (1961, part of the same “Faith Trilogy”), in which von Sydow plays the sexually frustrated and uncomprehending husband of a schizophrenic (Harriet Andersson). Seen together, the films offer a fascinating study in von Sydow’s ability to play those who suffer, and those struggling to understand the suffering of others. (No wonder he would go on to play Jesus Christ in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), his English-language debut.)

Von Sydow appeared in two of the three “Faith” films, and in all three entries of Bergman’s “Island Trilogy”: Hour of the Wolf (1968), Shame (1968), and The Passion of Anna (1969). Of the three, Shame is probably von Sydow at his cruellest, portraying a quasi-sadistic husband who readily throws off the shackles of morality during a civil war in an unnamed country (Shame was Bergman’s response to Vietnam). Shame is the only film in which the meticulous wordsmith Bergman ever allowed his actors to improvise: the scene in which Liv Ullmann (shy, affectionate) attempts to seduce her husband von Sydow (cold, his back turned to the camera for the entire scene) over a picnic lunch is striking. Though Ullmann does most of the work, their improvised exchange would not succeed if not for von Sydow’s faceless, terse responses: even his shoulders convey meaning.

Bergman loved Max von Sydow, and he loved Ullmann, indeed all the actors with whom he repeatedly collaborated. This is no more evident than in The Passion of Anna, in which Bergman simply gives the film over to his actors. That is, he invites Ullmann and von Sydow, and fellow Bergman stalwarts Bibi Andersson and Erland Josephson, to speak directly to the camera, breaking character to discuss their thoughts on the film itself. Aside from being a revolutionary breaking of the fourth wall, it’s also a rare opportunity to see von Sydow outside his character, discussing his craft. It’s a masterclass in the art of acting.

Max Von Sydow was more than his Bergman roles, of course. Paired again with Ullmann in The Emigrants (1971) and The New Land (1972), about poor Swedes who settle in 19th century America, the remarkable star power of the two non-English speaking leads resulted in major box office success – and an unusual (for a foreign language production) Oscar nomination in the Best Picture category.

Hollywood beckoned, too. The general public will, for better or for worse, always remember him as Father Merrin in The Exorcist (1973), a fundamentally silly horror film that is bolstered by von Sydow’s precious few minutes of screen time. As a priest quite literally wrestling with faith, the role makes for a nice (if cheesy) echo of his earlier Bergman roles. Turns in Three Days of the Condor (1975), Never Say Never Again (1983), and in Canadian comedy classic Strange Brew (1983) left him temporarily typecast as the vaguely foreign villain, though he maintained a steady stream of dramatic roles in such films as Pelle the Conqueror (1987), Hamsun (1996), and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007).

Carl Adolf “Max” von Sydow was born in Lund, Sweden on April 10, 1929. He appeared in his first film in 1949, at the age of twenty. He completed his last, the as-yet-unreleased Echoes of the Past, in his late eighties. In between, he served as Bergman’s occasional on-screen alter ego, exorcised a demon, terrorized James Bond, settled 19th century Minnesota, was thwarted by Bob and Doug McKenzie, and was twice nominated for an Academy Award.

As perceptive and nuanced as any of the greats, he long ago earned his place in the pantheon, up there with O’Toole and Olivier, Mastroianni and Mifune. An extraordinary talent, one who obviously loved acting and kept acting as long as he could, his loss is a loss to all cinema.

Sixty-three years ago Max von Sydow played chess against Death, and won a reprieve, however temporary, on behalf of all humanity. Our great cinematic knight, he showed us a tortured strength we might aspire to, along with the flaws that reflect who we really are. His roles could be difficult, even painful to watch, but in exposing himself – and therefore all of us – to scrutiny, he embodied everything a great actor should be.

Tack, Max. Vila i frid.