For a long time, spy novelist John le Carré kept his sights aimed squarely at the ugly underbelly of Cold War espionage: the tragic figures, the wasted resources, and – too often – the utter meaninglessness of it all. One clean agent sacrificed for the sake of another, dirtier, agent. An innocent civilian caught up in a vast international conspiracy. And threaded throughout, the very thin, grey line between spycraft and criminality.

Lately, though – and by lately, I mean the last 2-3 decades – le Carré has, rather admirably, cast his literary eye on the other hidden and not-so-hidden systems that govern so much of what we do, and how our world works. Le Carré was never just a spy novelist, but it’s been thrilling to follow along as he directly tackles such themes as corporate malfeasance (Exhibit A: The Constant Gardener), the global arms trade (Exhibit B: The Night Manager), and the general grotesqueries of contemporary geopolitics (Exhibit C: keep reading).

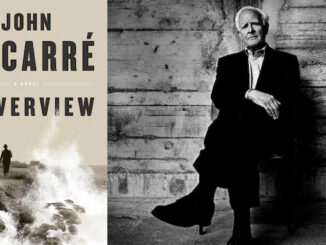

At 88 years old, John le Carré still has some stories to tell.

US vs THEM

In what may come as a surprise to readers, le Carré’s latest novel, Agent Running in the Field, is set, and is very much about, today. It’s the familiar spy story of old, yes, but the technology has improved (notwithstanding the charmingly old-fashioned reliance on pen, paper, and invisible ink), and its subject matter is ripped straight from the headlines.

Which is to say: Field is anti-Trump, anti-Putin, anti-Brexit.

It’s also a resounding condemnation of the decline and fall of the Anglo/American Empire, and a sad, frustrating, exploration of the consequences of that fall. Though a spy novel at heart, it’s also, perhaps inevitably, about the moral bankruptcy of today’s leaders – the ones we know about, and the ones hidden behind the scenes. This being a le Carré, it’s also exciting, a page-turner, and a first-rate spy yarn.

THE MIDDLE MANAGER

Agent Running in the Field tells the story of a just-over-the-hill MI6 agent who stumbles onto a potentially explosive double-agent scheme. Set primarily in London, with a couple brief jaunts abroad, it takes a very 21st century look at the concerns with which le Carré has been preoccupied since his first novel, Call For the Dead (published when le Carré was still in MI6!). In clear prose, peppered with the now-familiar lingo he in large part invented – tradecraft, “moles”, etc. – le Carré once again pulls back the curtain on the enigmatic and Matryoshka-like ways of the spy trade. And with all due respect to Ian Fleming: spying isn’t sexy.

Neither is Field‘s protagonist, Nat, who might best be described as an espionage middle manager. Though most of his contemporaries have long since risen to the rarefied heights of leadership, Nat remains stuck in the middle: overseeing field agents who do the exciting work, but with limited authority of his own. In the eyes of his university-aged daughter, who knows only his cover story, Nat is little more than a foreign service officer who never quite made the grade. In a way, she’s right.

But Nat has some redeeming qualities. For one, he is very, very good at recruiting and delicately handling his agents and sources. For another, he has a strong marriage with his social justice lawyer wife (who devotes her time to taking on Big Pharma, no less). Nat is also, amusingly, quite a good badminton player.

That these details eventually prove central to Nat’s story should come as little surprise to readers – let’s just call it Chekhov’s Shuttlecock – but taken together, they make for one of the more likeable, and sympathetic, of le Carré protagonists. George Smiley – he of Tinker, Tailor fame – was a bit of a depressive and altogether pitiable. In comparison, Nat, who spends significant portions of the novel downing pints with an angry young man prone to anti-Brexit diatribes (aren’t we all?), seems like rather a decent sort. If nothing else, Nat appreciates the human element, rather than exploit it as Smiley did.

It’s also, I think, revealing that le Carré chose to name – and model – two of Field‘s central characters after Michael Shannon and Florence Pugh, who so memorably costarred in the most recent le Carré TV adaptation. “Florence” and “Shannon” make for a cute in-joke, sure, but they also suggest, even subconsciously, the author’s desire that his characters be viewed in a more positive light than le Carré protagonists past.

BOJO and BOZO

If le Carré has always been cynical about the milieu in which his novels take place, he’s also long evinced an admiration for the best that Europe and Britain have to offer. Never nostalgia – he’s too smart for anything resembling admiration for Britain’s dismal colonial legacy – but at least a love for the good Anglo/European things. But tea and crumpets and evenings at the National Theatre only go so far, and it’s hard not to get the feeling that, after weathering Thatcherism, the Blair/Bush years, and the horrors of The D.Cameron, it was Brexit that finally did le Carré in.

Brexit certainly looms large over Agent Running in the Field. Nat works for MI6, and MI6 works for the government, therefore Nat is officially pro-Brexit. But Nat is also a sane and rational human being, and therefore profoundly and morally anti-Brexit. Moreover, Nat understands – and you don’t need capital-I Intelligence to figure this out – that decoupling Britain from Europe, and doubling down on the so-called “Special Relationship” between the UK and USA, is the quickest route to 21st century geopolitical irrelevance.

The Britain of le Carré’s past novels is – barring an 11th hour reprieve – dead. Brexit, in le Carré’s view, is the final nail in the coffin.

LE CARRÉ’S PEOPLE

le Carré, he the greatest of spy novelists (no one even comes close), has never been wrong about any of this. Britain’s toxic decline, the exploitation of the poor and the innocent, the rank injustices that belie the nature of western democracy: these themes percolate beneath the surface of his early works, and have only become more pronounced over time. Amusingly enough, le Carré in his 80s has become something of the archetypal British angry young man himself.

That anger extends to the bitter fate to which he consigns Britain at the end of Agent Running in the Field, even as he gives the novel’s central characters an unambiguously happy ending. It’s an interesting inversion of the typical le Carré finale, in which MI6 gets a “win” – they capture the double agent, they outmaneuver the Russian spymaster – but at a deep personal cost to the characters whom the readers have come to care about. This time, at least, it’s Britain that pays the price for having betrayed its own people too often, too callously, and for all the wrong reasons. To paraphrase Robert Bolt (a one-time colleague of le Carré’s at the Millfield School):

It profit a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world . . . but for Brexit?

JG