If Hiroo Onoda didn’t exist, Werner Herzog would have had to invent him.

Legendary filmmaker Herzog, chronicler of extreme individuals in extreme circumstances, has found a perfect subject in Onoda, the Japanese soldier who from 1944 to 1974 waged an occasionally bloody campaign of guerrilla warfare on the island of Lubang in the Philippines, operating on strict orders to maintain his position pending the glorious return of the long-since-surrendered Japanese Imperial Army. When Onoda was finally convinced to abandon his jungle home of three decades, he was the second-last Japanese holdout from WWII. (The lesser-known “final holdout”, Teruo Nakamura, was located and repatriated a few months after Onoda.)

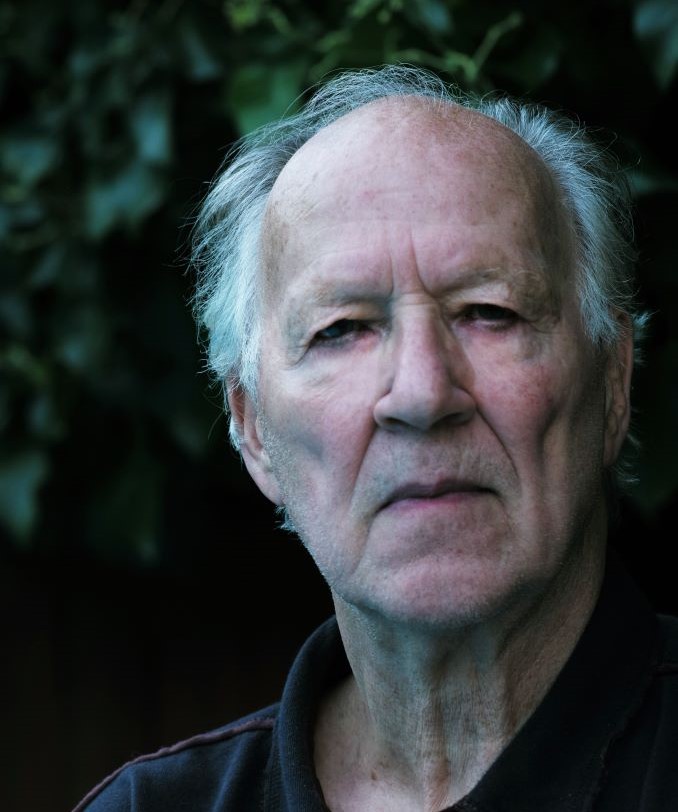

The Twilight World (subtitle: “A Novel“) is Herzog’s first work of literary fiction, though he has published several books before, most notably his Conquest of the Useless, documenting the intense experience of filming his masterpiece Fitzcarraldo in the jungles of Peru in 1981. On film, in both features – Fitzcarraldo; Aguirre, the Wrath of God; Rescue Dawn – and documentary – Grizzly Man; Encounters at the End of the World; Little Dieter Needs to Fly – Herzog long ago established himself as the preeminent observer of humanity at its most extreme. Herzog’s characters, fictional and nonfictional, have endured plane crashes, bear attacks, volcanoes, the coldest temperatures on the planet, and, in a recurring theme, the dark, bloody, boiling cruelty of the jungle. It is no surprise then, as Herzog explains in the preamble to this, his debut novel, that when asked, during a visit to Japan, who he was most interested in meeting in all of the country, he responded with a single word: “Onoda”.

HOLDING OUT

The Twilight World is a fictionalized retelling of the experiences of Lt. Hiroo Onoda, who for thirty years lived in the jungles of Lubang as one of the last “active” soldiers of WWII. In theme and structure, The Twilight World echoes several of Herzog’s films, especially Little Dieter Needs to Fly (and its fictionalized portrayal in Rescue Dawn), which documented the remarkable story of Lt. Dieter Dengler, a U.S. Navy pilot who escaped a Vietnam War prison camp and survived months in a hostile jungle environment.

The basic facts of the Onoda story are well-known. In 1944, as Japanese forces fled Lubang Island ahead of a U.S. military invasion, Lt. Onoda was given a secret mission – to stay behind, destroy the landing pier, blow up the airfield, and then, disappearing into the jungle, to undertake whatever means necessary to hamper the progress of the enemy army. Within the year, Onoda’s squad was reduced to four. By 1950, only three remained: Lt. Onoda, Corporal Shōichi Shimada, and Private First Class Kinshichi Kozuka. By 1974, only Onoda was left – still refusing to believe the war had ended, let alone in Japan’s defeat.

Onoda’s story reflects the uniquely Japanese historical phenomenon of the war holdout. While other conflicts and other countries have experienced similar incidents, something in the Japanese cultural makeup – note how Onoda diligently preserves a centuries-old samurai sword throughout his time on Lubang – has resulted in a disproportionate number of soldiers who keep fighting years or decades after their country’s defeat. Some thirteen Japanese WWII holdouts are accounted for, with rumours of others scattered across the Pacific, their island hideaways still to be found.

The Twilight World picks up with the fateful moment, in 1974, when a young Japanese adventurer tracks Onoda down and, for the first time ever, convinces the old soldier of the possibility the war really has ended. Departing with a photograph as proof-of-life, and a promise to return with whomever of Onoda’s superior officers is still alive, Norio Suzuki leaves Onoda behind to sit and reflect on the past thirty years. It is here, in Onoda’s reminiscences of life on Lubang, that the bulk of the novel is situated.

HELL IN THE PACIFIC

Onoda’s story is so incredible that it’s a testament to Herzog’s writing that The Twilight World rarely feels sensationalized. Despite the mythology that sprung up around him – local villagers referred to him as the “spirit of the jungle” – Onoda was very much a man, albeit one of intense military discipline, whose daily life largely revolved around finding food, shelter, and water. Also, staying out of sight of the Philippine police and soldiers who would occasionally come looking for him, blasting pre-recorded messages in Japanese announcing that the war had ended. Despite these search efforts, and the dropped leaflets, and even one occasion in which Onoda’s own brother visited the island and pleaded, over megaphone, for him to come home, it would take thirty years before Onoda would finally concede the war was over.

The book is divided into roughly three sections – a preamble and prologue set at and following Onoda’s 1974 discovery; a detailed recounting of the 1944-45 period in which Onoda establishes the tactics that would come to define his decades on the island; and a too-short series of anecdotes covering the period from roughly the 1950s through the 1970s, as Onoda grows older and loses squad-mates. (This might qualify as a historical “spoiler”, but the sad truth is that most of Onoda’s companions perished.)

THE BURDENS OF DREAMS

Werner Herzog may very well be the greatest living director, moving effortlessly between fiction and nonfiction (and sometimes weaving the two together, as in Little Dieter Needs to Fly / Rescue Dawn). Herzog is certainly the most consistent, producing dozens of great – or at least, interesting – films across his sixty-year career. (His next documentary, Theatre of Thought, premieres at TIFF this month.)

Like his films, The Twilight World is intelligent, thoughtful, and manages to thread a delicate line between sympathy and objectivity. The matter-of-factness with which Herzog describes Onoda’s jungle life, for example his painstaking process for storing ammunition in homemade palm oil, pairs nicely with more lyrical passages that capture a feeling of aloneness and decay.

Above all else, Herzog is a bard of the jungle, and of dreams. His rightfully famous monologues on the obscenity of the jungle and the overwhelming indifference of nature encapsulate a worldview that sees our natural world as a thing of awful beauty – something to be admired and feared all at once. It is that perspective that suffuses The Twilight World, with at least one passage, describing “a natural dream sibling equipped with all the unquestioning certainty of dreams…. the jungle; the swamp; the leeches; the mosquitoes; the screams of the birds; thirst; the bumpy, itching skin”, rivalling anything in Herzog’s filmography. The Onoda character, too – that is, Herzog’s version of Onoda – can be found musing on the passing of time in decidedly Herzogian terms: “At this point, time stops still for weeks. Or rather, it doesn’t stop, it simply no longer occurs.” Elsewhere: “There is one unvarying constant: everything in the jungle is at pains to strangle everything else in the battle for sunlight.”

The writing is beautiful, unsettling, and believable. One can imagine the real Lt. Onoda, entering year nine or seventeen or twenty-four of his arduous jungle life, tracing similar thoughts across his confused, feverish mind. Echoing a (probably apocryphal) Mark Twain, Herzog writes in his preamble, “What was important to the author was something other than accuracy, some essence he thought he glimpsed when he encountered the protagonist of the story.” That sounds about right.

CINEMATIC FICTION

At the risk of being reductive, Herzog the writer sounds very much like Herzog the filmmaker. This is, on the whole, a good thing. We already know Herzog to be an articulate, erudite chronicler of life in extremis, and there are times, especially when The Twilight World‘s omniscient narrator slips from the third- to the second-person, when you can practically picture Herzog standing in the jungle next to Onoda, simultaneously marvelling at and recoiling from the horrors around him. Credit too to the translation, by poet Michael Hoffman, who does an admirable job of recreating Herzog’s famous “voice” without ever coming across as clichéd. (Though a fluent English speaker, it does not appear Herzog worked on the translation.)

That said, The Twilight World does occasionally read more like a film outline or an excerpt from some unproduced documentary, than a novel proper. While not necessarily a bad thing, there are times, particularly in montage-like sequences that offer up impressions rather than fully formed pictures, where The Twilight World practically begs for certain details to be coloured in. Readers will be forgiven for having Wikipedia or Google Images open while reading.

MYTH AND MAN

Herzog, despite the lazy parodies, is a born humanist. One thing that shines through The Twilight World is the author’s utter fascination with what makes us human, particularly when the normal trappings of humanity – family, community, a home – are stripped away. Dieter Dengler survived a jungle prison. Kaspar Hauser survived a childhood locked in a darkened cell with no human contact. Lt. Hiroo Onoda spent thirty years in the jungle, staving off hunger, thirst, insects, and a self-imposed, nightmarish burden that might have destroyed even the bravest Robinson Crusoes among us.

On the one hand, there’s something endlessly fascinating about this one man and his strict adherence to a code of honour hearkening back to a nearly mythological era of Japanese civilization. On the other hand, Onoda was a thirty-year terror to local villagers, raiding and looting and, on occasion, killing all in the name of a defunct army and a fundamentally meaningless private war. Herzog isn’t exactly ambivalent about this – the mere act of choosing to tell this story suggests a certain sympathy, even identification with its central figure – though he does, for the most part, resist the temptation of turning Onoda into a heroic figure.

Herzog (if not ever entirely Onoda himself) clearly understands the cruelty of warfare, and it’s to the novel’s credit that at no point does The Twilight World glorify any of the violence meted out by, or against, Onoda. These incidents, of needless confrontation between the Japanese holdouts and local police, security guards, or simple farmers, are portrayed in an unexciting, fact-based manner that strips them down to their essentials. In so doing, The Twilight World undercuts the idea of Onoda as a war hero, something he was heralded as back home.

Tellingly, Onoda’s ghostwritten memoir, No Surrender, contains no mention of having killed any locals. The Twilight World, for all its dreamlike imagery and time spent dwelling in Onoda’s inner thoughts, at least acknowledges that this story was never Onoda’s alone.

*

Visit the website for Werner Herzog’s The Twilight World here.

Wondering where to start with Herzog’s filmography? Check out this list of the Top 10 Greatest Herzog films.