Georges Bizet’s masterpiece Carmen, first performed in 1875, is opera.

What we mean is, that in addition to getting the important things right – like wonderful music, great story, and visual spectacle – it is the opera that has most embedded itself in popular culture. When you picture opera, you probably picture Wagner’s The Valkyrie. But when you conjure up the sound of opera, you’re probably hearing Carmen.

As the second opera of COC’s 2022-2023 season, Carmen is a safe, audience-friendly choice that reminds us why, beyond all the Simpsons jokes and TV commercials and countless other uses (and misuses), Bizet’s opera is a deserved centrepiece of the operatic repertoire. That said, the COC’s serviceable, if occasionally clumsy, production also suffers from some odd choices that distract – and detract.

For a 21st century audience, and a 21st century opera company, some of Carmen‘s racial and gender aspects can be highly problematic. For the most part, the COC has done a decent job of updating Carmen – and Carmen – by emphasizing her autonomy in a way that makes the men look especially bad. At the same time, and as we’ll get to below, some well-intentioned revisions ring hollow.

But let’s start with the good stuff. Every Carmen needs a great Carmen, and Tunisian-Canadian soprano Rihab Chaieb was far and away the best part of the October 22nd performance which Toronto Guardian attended. A rising star – she previously appeared with the COC as Waltraute in the aforementioned The Valkyrie (2015) and Soeur Mathilde in Dialogues des Carmélites (2013) – Carmen is a fine showcase for Chaieb’s talent as both a musician and an actor. Her beautiful and lyrical voice, combined with the haughtiness and charm required of one of opera’s most iconic roles, endeared her to the (admittedly partial) hometown audience. You would never have known that Chaieb is playing, in effect, second fiddle to soprano megastar J’nai Bridges, who the COC landed for six of the eight performances this run. (Chaieb performed only on the 20th and 22nd.)

Tenor Marcelo Puente plays Carmen’s obsessed lover Don José, the soldier who throws away everything for the sake of an intense “love” that could easily be mistaken for lust. Puente is a fine singer, but he puts in such a leaden performance – all stomping around stage, declaiming to no one in particular – that it’s hard to take him seriously as the fiery lover that the libretto (by Ludovic Halévy and Henri Meilhac) calls for. Faring somewhat better is baritone Lucas Meachem as the toreador Escamillo. Escamillo really has one job – to sing that aria – and while he certainly has the voice for it, his otherwise dramatic entrance is undercut by a rather silly sunglasses-and-rhinestones costume, garish even by the standards of bullfighters.

Rounding out the main cast is Lebanese-Canadian soprano Joyce El-Khoury. She, too, sings well enough as Micaëla, the “girl next door” sent (by Don José’s mother, no less!) to bring him back to the quiet life of their home village. El-Khoury only has two scenes of note, earning deserved sympathy as the kind, innocent woman in love with a man who barely notices her. Unfortunately, El-Khoury’s excessively warbly coloratura is, in this instance, unsuitable for a character whose softness and sweetness is supposed to contrast with the more brazen Carmen. Knowing El-Khoury’s talents as a bel canto soprano, we can probably chalk this one up to the musical direction from conductor Jacques Lacombe, rather than any fault of El-Khoury herself.

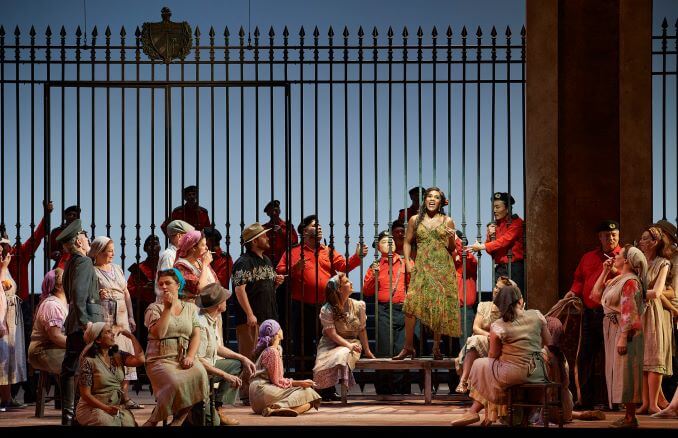

On the positive side, the set design is fantastic. The Act II café – site of Escamillo’s aforementioned toreador aria – is a standout, effectively conjuring up a hot Seville evening, the stars shining brightly above. Minor concerns about Escamillo’s outfit aside, the costumes for the main cast are also rather lovely. Carmen looks like the classic Carmen while mostly avoiding clichés, though the red dress does make an appearance. Credit, too, to costume designer François St. Aubin for wardrobe choices that allow Carmen to own her sexuality without being overly sexualized. Carmen is very much a story about men projecting their desires onto women; it’s important that her costume design isn’t itself a product of the male gaze.

However! Some details of the COC design are plain confusing, beginning with the fact that most of the background/civilian characters appear in quasi-modern dress, despite the more classical costumes worn by the main cast. Between the children wearing modern t-shirts and athletic wear, and the choristers who look like they just stepped off a Carnival cruise, it’s as if director Joel Ivany ran out of time and had to dash over to the local Old Navy at the last minute. Confusing things even more are minor background details – like a jukebox and old-timey camera – that, bizarrely, suggest a 1930/1940s setting despite the otherwise 19th century production design. If so, this would place the COC’s Carmen at the outset of the reign of fascist dictator Francisco Franco. Which, frankly, is super weird? Honestly, though, I suspect I probably just put more thought into this than director Ivany and his team ever did.

Slightly more understandable, if ill-advised, is the decision to replace the “g-word” with “Romani” in the English-language surtitles. While I’m all for divesting opera of its more problematic aspects – and I’m happy to be rid of that racist, outdated word – this is probably too much of an overcorrection. For one thing, the actual sung word in French – which the COC left intact – is bohémienne, which has a perfectly acceptable, and inoffensive, English-language equivalent. More worrisome is that, by falsely ascribing contemporary values to historical characters, the COC diminishes an essential element of the story: that Carmen was exoticised by the men around her, that she was looked down upon by the prejudiced society she inhabited. Look, it’s a complicated issue, and this is not the first time the COC has flubbed it when trying to be culturally sensitive, but there are surely better ways to confront this ugly cultural history, than to simply scrub it clean.

That (obviously fraught) issue aside, the COC’s Carmen is fun, engaging, and highly entertaining. That said, the combination of poor directorial choices – don’t even get me started on the part where the audience is (shudder) encouraged to clap along with the music – does Carmen, and Bizet, a disservice. Carmen might be the epitome of opera, but the COC’s production of Carmen is unlikely to stand the test of time.

*

Tickets for the COC’s Carmen are available here.