The Royal Ontario Museum’s newest exhibition, Anishinaabeg: Art & Power has officially opened to the public. It’s a thoughtful and artistic journey of one of the most diverse Indigenous culture in North America that includes several works by artist Norval Morrisseau, one of the founding members of the Woodland School of Art — often referred to as the “Picasso of the North” for establishing the “Woodland” style of art using bold colours and thick black outlines.

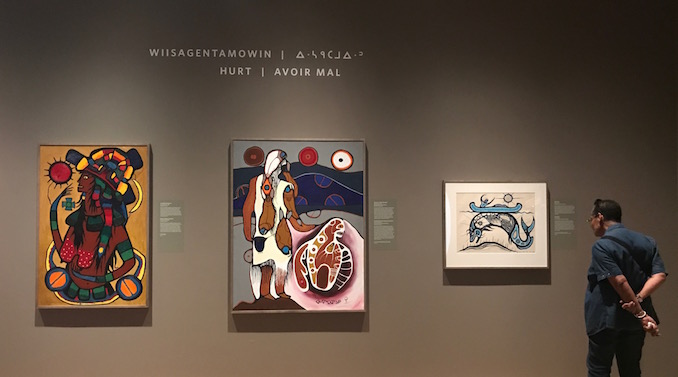

There is no particular flow that one should follow in the exhibition, which I was told was purposely done. But if you were to see it from a bird’s eye view, the centre of the exhibition features material of early 19th century from the Great Lakes area. Then, around that are a series of clear cases filled with artifacts from daily life, commerce and incredible bead work of Anishinaabeg art from the late 19th century into 20th century –a time when they began mingling with other cultures. Along the walls of the exhibition are paintings that are grouped in themes including creation, transformation, and hurt. We also discovered a number of contemporary pieces by Anishinaabeg artists. But if you come across artist and co-curator Saul J. Williams walking around the exhibit, I strongly suggest you make time for a chat.

Williams is from the North Caribou Lake First Nation in northern Ontario. He is an artist with the Woodlands School of Art and not only was he brought in to the ROM to guest co-curate this exhibition but his work also is on display. When you enter the exhibition there is a four minute video of Williams given a brief introduction to the exhibit as well as his beautifully detailed piece titled “White Women and Their Plants”. He also was at the preview along side the curator team chatting up members as they had their sneak peek. I overheard him in conversation. A bit soft-spoken but happy to take you beyond the descriptions on the wall.

I lightly tapped him on the shoulder and introduced myself. I had hoped to not take too much of his time as I’m sure many others would want to chat with him. I asked him if he could tell me stories about any three pieces that are on display in the exhibition.

He knew immediately which ones he wanted to talk about and lead me to the “Hurt” themed section of the exhibition tucked in one of the corners. I’m sure there’s a great story behind ever work of art here. “I was asked to put stories to the paintings,” he said in a calm and soft spoken voice. “So, the labels are based on my interpretation of the Woodland School paintings that are in the exhibit. They tell about the values and beliefs and legends around our people. But you only want me to talk about three?” he smiled.

I smiled back. Something tells me that he’s very much like my dad…a storyteller.

Hurt is something all nations go through but the Indigenous people consider hurt as a result of bad spirits or curses by ancestors. But in order to move forward and to get past hurt, they need to transform or transport themselves to a new place. Williams begins to tell me about a piece titled “Thunderbird Woman” by Norval Morrisseau.

“This painting here interprets the power of the mother. Whatever mother’s eat they pass through to their children. I guess you can say we invented that thinking ‘you are what you eat’. You see there is lightening bolts going through the Thunderbird woman as she feeds the baby Thunderbirds. It can be good but it also can be disease too that would hurt her babies. She might not even know that at that time.”

Another piece Williams mentioned along the same theme was a large circular and more contemporary image titled Meditations on Red #2 by Nadia Myre from the Kitigan Zibi First Nation in Quebec. “I really like this work. It makes us think about blood content of the Indigenous people. It tells us about the problem she had when she tried to cross the border to the US. They told her she was not Indigenous enough,” explained Williams. The beads shown in this image represents each drop off blood from white blood cells and red ones. Myre had to prove that she was more than 50% Indigenous blood.

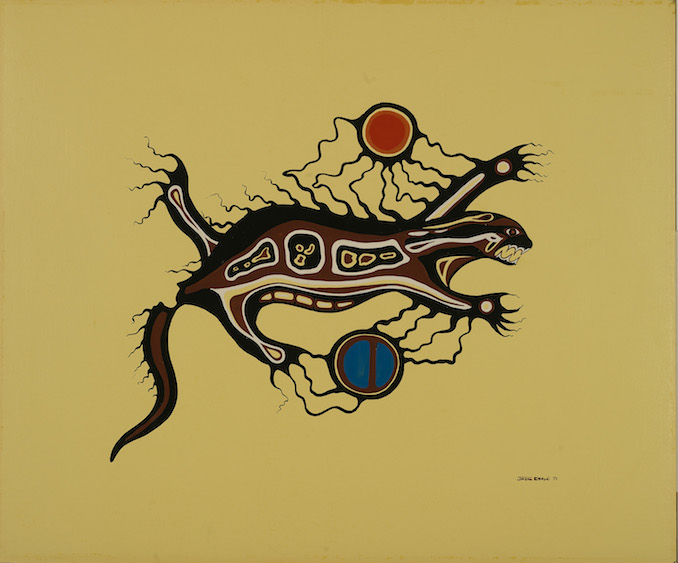

Williams explained that often Woodland artists have incorporated legends and stories passed down from the previous generations. “This piece of art by Morrisseau tells us the story about the people who we think did the rock paintings that we called the Memekweshik because they lived in the rocks. They were so shy they would only come out at night time. They were said to be hairy and had no nose. That’s how this story about Woodland art blossomed.”

Williams had a spark in his eye as he quickly started walking towards another contemporary piece in the exhibition by Barry Ace of Manitoulin Island. “You have to see this guy’s work. He made a traditional bandolier bag out of old radio parts,” he laughs. “He has a really interesting mind. He’s an artist. You can see the old transistor radio parts and the wires.” He explained that Ace was showing a parallel between electricity and the spirits that his ancestors associated with beadwork.

And what about his painting that is exhibited titled White Women and Their Plants? Williams tells us that when he was growing up he only saw flowers when he visited other people’s homes. “I thought about my mother’s house. In her house you would never see flowers. In our community the only time you would see flowers is at a funeral.”

Another prominent Woodland artist, Jackson Beardy from Island Lake in Manitoba, has an important painting here on display. Williams points out a painting titled “Fisher and a broken tail. “In my community there’s a legend similar to this painting. When man met wolverine he pulled out his arrow and bow. He shot wolverine and broke his tail. A few days later the wolverine met with all beings and he was in great distress. He said ‘How can I show others that I mean no harm when I have no tail to wag?’ What that also implies is we have to respect all beings and whatever interests they have. However different they look. We have to respect everybody.”

“Was that more than three?” I thought to myself . We laughed and I thanked him for his time but then he returned with a few more wonderful stories he wanted to share…and I was grateful.

Anishinaabeg: Art & Power exhibition is open for viewing at the Royal Ontario Museum until November 19, 2017. For more information visit rom.on.ca